|

Series:

Library

Source:

Author:

Edward G. Browne

Subtopics:

Reference:

Related Articles:

Book Review:

A Year

Amongst the Persians

Related Links:

|

CHAPTER XIII

YEZD

"East-wind, when to Yezd thou wingest, say thou to its sons from me,

May the head of every

ingrate ball-like ‘neath your mall-bat be.

What though from your

dais distant, near it by my wish I seem,

Homage to your King I render, and I make your praise my theme."

(Hafiz, translated by

Herman Bicknell.)

Scarcely had I cleansed myself

from the dust of travel, when I was informed that one had come who would have

speech with me; and on my signifying my readiness to receive: him, a portly old

man, clad in the dull yellow raiment of the I guebres, was ushered in, Briefly

saluting me, he introduced i himself as the Dastur Tir-andaz, high-priest of the

Zoroastrians; of Yezd, and proceeded to inform me that the Governor of the city,

His Highness Prince 'Imadu'd-Dawla, having learned that a European had just

arrived in the town, had instructed him to interview the said European and

ascertain his nationality, the business which had brought him to Yezd, and his

rank and status, so that, if he should prove to be “distinguished” (muta-shkhkhis),

due honour might be shown him.

“As for my nationality,” I

replied, “I am English. As for my business, I am traveling for my own

instruction and amusement, and to perfect myself in the Persian language. And as

for my rank, kindly assure the Governor that I have no official status, and am

not 'distinguished' at all, so that he need not show me any honour, or put

himself out of the way in the least degree on my account.”

“Very good,” answered the

fire-priest, "but what brings you to Yezd? If your only object mere to learn

Persian, you could have accomplished that at Tehran, Isfahan, or Shiraz, without

crossing these deserts, and undergoing all the fatigues involved in this

journey.”

“Well,” I said, “I wished to

see as well as to learn, and my travels would not be complete without a sight of

your ancient and interesting city. Besides which, I desired to learn something

of those who profess the faith of Zoroaster, of which, as I understand, you are

the high-priest.”

“You would hardly undergo all

the fatigues of a journey across these deserts for no better reason than that,”

he retorted; "you must have had some other object, and I should be much obliged

if you would communicate it to me.”

I assured him that I had no

other object, and that in undertaking the journey to Yezd I was actuated by no

other motive than curiosity and a desire to improve my mind. Seeing, however,

that he continued sceptical, I asked him point-blank whether he believed my word

or not; to which he replied very frankly that he did not. At this juncture

another visitor was announced, who proved to be Ardashir Mihraban himself. He

was a tall, slender, handsome man, of about forty-five or fifty years of age,

light-complexioned, black-bearded, and clad in the yellow garments of the

Zoroastrians; and he spoke English (which he had learned in Bombay, where he had

spent some years of his life) fluently and well. After conversing with me for a

short time, he departed with the Dastur.

Hardly had these visitors left

me when a servant came from the Seyyids to whom I had letters of introduction,

to inform me that they would be glad to see me as soon as I could come. I

therefore at once set out with the servant, and was conducted by him first to

the house of Haji Seyyid M---, who, surrounded by some ten or a dozen of his

friends and relatives, was sitting out in the courtyard. I was very graciously

received by them; and, while sherbet, tea, and the kalyan, or water-pipe,

were successively offered to me, the letter of introduction given to me by Mirza

'Ali was passed round and read by all present with expressions of approval,

called forth, as I suppose, not so much by the very flattering terms in which it

had pleased my friend to speak of me, as by what he had written concerning my

eagerness to learn more of the Babi religion, to which my new friends also

belonged. Nothing was said, however, on this topic; and, after about an hour’s

general conversation, I left in company with Mirza Al--- to visit his father

Haji Mirza M--- T--- to whom also I had a letter of introduction. There I

remained conversing till after dusk, when I returned to the caravansaray, and,

while waiting for my supper, fell into so profound a slumber that my servant was

unable to wake me.

To go supperless to bed

conduces above all things to early rising, and by 6.30 a.m. on the following

morning I had finished my breakfast, and was eager to see something of the city

of Yezd. My servant wished to go to the bath, but the Erivani, who had attached

himself to me since I first made his acquaintance, volunteered to accompany me.

We wandered for a while through the bazaars, and he then suggested that we

should enquire of some of the townsfolk whether there was any public garden

where we could sit and rest for a time. I readily acquiesced in this plan, and

we soon found ourselves in the garden of Dawlatabad, where we sat in a shady

corner and conversed with an old; gardener who had been for thirteen months a

slave in the hands of the Turcomans. He had been taken prisoner by them near the

Kal'at-i-Nadiri about the time that Hamze Mirza w as besieging Mashhad (1848),

and described very graphically his experiences in the Turcoman slave-market; ho

w he and his companions in misfortune, stripped almost naked, were inspected and

examined by intending purchasers, and finally knocked down by the broker to the

highest bidder. He had finally effected his escape during: a raid into Persian

territory, in which he had accompanied the marauders as a guide, exactly after

the manner of the immortal Haji Baba. He and the Erivani joined cordially in

abusing the Turcomans, whom they described as more like wild beasts than men.

“They have no sense of fear,” said the latter, “and will never submit, however

great may be the odds against them; even their women and children will die

fighting. That was why the Russians made so merciless a massacre of them,, and

why, after the massacre was over, they piled up the bodies of the slain into a

gigantic heap, poured petroleum over it, and set it on fire, that perhaps this

horrible spectacle might terrify the survivors into submission.”

About mid-day we returned to

the caravansaray, and I was again forced to consider my plans for the future,

for Baba Khan came to enquire whether he should wait to convey me back to Dihbid,

or whether I intended to proceed to Kirman on leaving Yezd. I paid him the

remainder of the money due to him, gave him a present o f seven krans,

and told him that, unless he heard from me to the contrary before sunset, he

might consider himself free to depart.

Later in the afternoon, two

Zoroastrians came to inform me that Ardeshir Mihraban, in whose employment they

were, was willing to place his garden and the little house in it at my disposal

during my stay at Yezd. It had been occupied about a month before by another

Englishman, Lieutenant H. B. Vaughan, who had undertaken a very adventurous and

arduous journey across Persia, from Bandar-i-Linge, on the Persian Gulf, to

Damghan or Shahrud, on the Mashhad-Teheran road, and who had tarried for some

while at Yezd to make preparations for crossing the western corner of the great

Salt Desert. I of course gratefully accepted this offer, for the caravansaray

was not a pleasant dwelling place, and besides this, I was ‘anxious to enjoy

more opportunities of cultivating the acquaintance of the Zoroastrians, for

which, as I rightly anticipated, this arrangement would give me exceptional

facilities. I could not repress a feeling of exultation when I reflected that I

had at length succeeded in so isolating myself, not only from my own countrymen,

but from my co-religionists, that the most closely allied genus to which I could

be assigned by the Yezdis was that of the guebres, for whom I already

entertained a feeling of respect, which further knowledge of that much-suffering

people has only served to increase.

Haji Safar was out when this

message was brought to me, and, as I could not leave the caravansaray until I

had instructed him as to the removal of my baggage, we were compelled to await

his return. During this interval a message came from Haji Seyyid M---, asking me

to go to his house, whither, accordingly, on my servant's return, I proceeded in

company with the two Zoroastrians, one of whom, named Bahman, spoke English

well.

On arriving at Haji Seyyid

M-‘s house, I was delighted to find a theological discussion in progress. An

attempt was evidently being made to convert an old mulla, of singularly

attractive and engaging countenance, to the Babi faith. Only one of the Babis

was speaking, a man of about thirty-five years of age, whose eloquence filled me

with admiration. It was not till later that I learned that he was 'Andalib

(“the Nightingale”), one of the most distinguished of the poets who have

consecrated their talents to the glory of the New Theophany. “And so in every

dispensation,” he resumed, as soon as I had received and returned the greetings

of those present, “the very men who professed to be awaiting the new

Manifestation most eagerly were the first to deny it, abandoning the ‘Most Firm

Hand-hold’ of God’s Truth to lay hold of the frail thread of their own

imaginings. You talk of miracles; but of what evidential value are miracles to

me, unless I have seen them? Has not every religion accounts of miracles, which,

had they ever taken place, must, one would have thought, have compelled all men

to believe; for who would dare, however hard of heart he might be, to fight with

a Power which he could not ignore or misunderstand! No, it is the Divine Word

which is the token and sign of a prophet, the convincing proof to all men and

all ages, the everlasting miracle. Do not misunderstand the matter: when the

Prophet of God called his verses “signs” (ayat), and declared the Kur'an

to be his witness and proof, he did not intend to imply, as some vainly suppose,

that the eloquence of the words was a proof. How, for instance, can you or I,

who are Persians, judge whether the eloquence of a book written in Arabic be

supernatural or not? No: the essential characteristic of the Divine Word is its

penetrative power (nufudh): it is not spoken in vain, it compels, it

constrains, it creates, it rules, it works in men’s hearts, it lives and dies

not. The Apostle of God said, ‘in the month of Ramazan men shall fast from

sunrise to sunset.’ See how hard a thing this is; and yet here in Yezd there are

thousands who, if you bade them break the fast or die, would prefer death to

disobedience. Wherever one arises speaking this Word, know him to be a

Manifestation of the Divine. Will, believe in him, and take his yoke upon you.”

“But this claim,” said the old

mulla, “this claim! It is a hard word that He utters. What can we do or

say?”

“For the rest, He hath said

it,” replied. 'Andalib, “and it is for us, who have seen that this Divine

Word is His, to accept it.” There was silence for a little while, and then the

old mulla arose with a sigh, and repeating, “It is difficult, very

difficult," departed from our midst.

Soon afterwards I too left,

and, accompanied by my Zoroastrian friends, made my way to the garden of

Ardashir Mihraban, situated at the southern limit of the town, hard by the open

plain. I found my host and the old fire-priest awaiting me, and received from

both of them a most cordial welcome. The letter informed me with some elation

that the Governor, Prince Imadu'd-Dawla, had, in spite of my representations

(which he, like the Dastur, no doubt regarded as the fabrications as an

accomplished liar, whose readiness in falsehood afforded at least some

presumptive evidence of a diplomatic vocation), decided to treat me as "

distinguished,” and would on the morrow send me a lamb and a tray of sweetmeats

as signs of his goodwill. “His Highness wished to send them sooner,” he

concluded, "but I told him that you were not yet established in a suitable

lodging, and he therefore consented to wait. When the presents come, you will

have to call upon him and express your thanks.” I was rather annoyed at this,

for “distinction” in Persia means much useless trouble and expense, and I wished

above all things to be free and unconstrained; but I did not then know Prince 'Imadu'd-Dawla

for what he was, the most just, righteous, and cultured governor to be found in

any town or province of Persia. Devotion to philosophical studies, and the most

tolerant views of other religions, did not prevent him from strictly observing

the duties laid upon him by his own creed; he was adored by the poor oppressed

Zoroastrians, who found in him a true protector, and, I believe, by all

well-disposed and law-abiding persons: and it was with a very sincere sorrow

that I learned, soon after my return to England, that he had been dismissed from

the office which he so nobly and conscientiously filled.

The change from the hot, dusty

caravansaray to this beautiful garden was in itself a great pleasure, and my

delight was enhanced by the fact that I was now in an environment essentially

and thoroughly Zoroastrian. My servant and the Erivani, indeed, still bore me

company; but, except for them and occasional Musulman and Babi visitors, I was

entirely thrown on the society of the yellow-robed worshippers of fire. The old

priest, Dastur Tir- andaz, who at first seemed to regard me with some suspicion,

was quite won over by finding that I was acquainted with the spurious “heavenly

books " known as the Desatir, about the genuineness of which neither he

nor Ardeshir appeared to entertain the slightest doubt. Ardashir sat conversing,

with me, after the others had departed, for it had been stipulated by Haji

Seyyid M--- that my meals were to be provided by himself; and as his house was

at some distance from the garden, it was nearly 10 p.m. before I got my supper.

"Khane-i-du ked-banu na-rufte bihtar" (“The house with two landladies is

best unswept”), remarked my host, as the night advanced without any sign of

supper appearing. However, the time was not wasted, for I managed to get

Ardashir to talk of his religion and its ordinances, and especially of the

kushti or sacred cord which the Zoroastrians wear. This consists of

seventy-two fibres woven into twelve: strands of six fibres each, the twelve

strands being further woven into three cords of four strands each. These three

‘cords, which are plaited together to form, the kushti, represent the three

fundamental principles of the Zoroastrian faith, good thoughts (hu-manishni),

good words (hu-go'ishni), and good deeds (hu-kunishni), the other

subdivisions having. Each in like manner a symbolical meaning. The investiture

of the young Zoroastrian with the kushti admits him formally to the

church of “those of the Good Religion” (Bih-dinan) ; and he is then

taught how to tie the peculiar knot wherewith it must be refastened at each of

the panj-gah, or five times of prayer. Ardashir also spoke of the duty

incumbent on them of keeping pure the four elements, adding that they did not

smoke tobacco out of respect for fire.

Although of the three weeks

that I spent at Yezd there was not one day which passed unprofitably, or on

which I did not see or hear some new thing, I think that I shall do better to

disregard the actual sequence of events in recording what appears worthy of

mention, so as to bring together kindred matters in one connection, and so avoid

the repetitions and ruptures of sequence which too close an adherence to a diary

must necessarily produce.

First, then, of the

Zoroastrians. Of these there are said to be from 7000 to 10,000 in Yezd and its

dependencies, nearly all of them being engaged either in mercantile business or

agriculture. From what I saw of them, both at Yezd and Kirman, I formed a very

high idea of their honesty, integrity, and industry. Though less liable to

molestation now than in former times, they often meet with ill-treatment and

insult at the hands of the more fanatical Muhammadans, by whom they are regarded

as pagans, not equal even to Christians, Jews, and other “people of the book” (ahlu'l-kitab).

Thus they are compelled to wear the dull yellow raiment already alluded to as a

distinguishing badge; they are not permitted to wear socks, or to wind their

turbans tightly and neatly, or to ride a horse; and if, when riding even a

donkey, they should chance to meet a Musulman, they must dismount while he

passes, and that without regard to his age or rank.

So much for the petty

annoyances to which they are continually subject. These are humiliating and

vexatious only; but occasionally, when there is a period of interregnum, or when

a bad or priest-ridden governor holds office, and the "lutis," or roughs, of

Yezd wax bold, worse befalls them. During the period of confusion which

intervened between the death of Muhammad Shah and the accession of Nasiru'd-Din

Shah, many of them were robbed, beaten, and threatened with death, unless they

would renounce their ancient faith and embrace Islam; not a few were actually

done to death. There was one old Zoroastrian still living at Yezd when I was

there who had been beaten, threatened, and finally wounded with pistol shots in

several places by these fanatical Muslims, but he stood firm in his refusal to

renounce the faith of his fathers, and, more fortunate than many of his

brethren, escaped with his life.

So likewise, as I was informed

by the Dastur, about twelve Years previously the Muhammadans of Yezd threatened

to sack the Zoroastrian quarter and kill all the guebres who would not consent

to embrace Islam, alleging as a reason for this atrocious design that one bf the

Zoroastrians had killed a Musulman. The governor of Yezd professed himself

powerless to protect the guebres, and strove to induce them to sign a document

exonerating him from all blame in whatever might take place; but fortunately

they had the firmness to refuse compliance until one of the Musulmans who had

killed a Zoroastrian woman was put to death, after which quiet was restored.

On another occasion a Musulman

was murdered by another Musulman who had disguised himself as a guebre, The

Muhammadans threatened to sack the Zoroastrian quarter and make a general

massacre of its inmates, unless the supposed murderer was given’up. The person

whom they suspected was one Namdar, a relative of the chief fire- priest. He,

innocent as he was, refused to imperil his brethren by remaining amongst them.

“I will go before the governor,” he said, “for it is better that I. should lose

my life than that our whole community should be endangered.” So he went forth,

prepared to die; but fortunately at the last moment the real murderer was

discovered and put to death, Ardashir's own brother Rashid was murdered by

fanatical Musulmans as he was walking through the bazaars, and I saw the tablet

put up to his memory in one of the fire-temples of Yezd.

Under the enlightened

administration of Prince 'Imadu'd-Dawla, the Zoroastrians, as I have already

said, enjoyed comparative peace and security, but even he was not always able to

keep in check the ferocious intolerance of bigots and the savage brutality of

lutis. While I was in Yezd a Zoroastrian was bastinadoed for accidentally

touching with his garment some fruit exposed for sale in the bazaar, and

thereby, in the eyes of the Musulmans, rendering it unclean and unfit for

consumption by true believers. On another occasion I heard that the wife of a

poor Zoroastrian, a woman of singular beauty, was washing clothes near the town,

when she was noticed with admirations by two Musulmans who were passing by. Said

one to the other, “She would do well for your: embraces." “Just what I was

thinking," replied the other wretch, who thereupon approached her, clasped her

in his arms, and tried to kiss her. She resisted and cried for help, whereupon

the Musulmans got angry and threw her into the stream. Next day the Zoroastrians

complained to the Prince-Governor, and the two cowardly scoundrels were arrested

and brought before him. Great hopes were entertained by the Zoroastrians that

condign and summary punishment would be inflicted on them; but some of the

mullas, acting in concert with the Maliku't-tujjar or chief

merchant of Yezd (a man of low origin, having, as was currently reported,

koli or gipsy blood in his veins), interfered with bribes and threats, and

intimidated an old Zoroastrian, who was the chief witness for the prosecution,

that he finally refused to say more than that he had heard the girl cry out for

help, and on looking round had seen her in the water. I know not how the matter

ended, but I greatly fear that justice was defeated.

On another occasion, however,

the Prince-Governor intervened successfully to check the following unjust and

evil practice. When a Zoroastrian renounces his faith and embraces Islam, it is

considered by the Musulmans that he has a right to the property and money of his

unregenerate kinsmen. A case of this sort had arisen, and a sum of ninety

tumans (nearly L28) had been taken by the renegade from his relatives. The

latter appealed to the Prince, who insisted on its restoration, to the

mortification of the pervert and his new friends, and the delight of the

Zoroastrians, especially old Dastur Tir-andaz who, when he related the incident

to me, was almost incoherent with exultation, and continually interrupted his

narrative to pray for the long life and prosperity of Prince "Imadu'd-Dawla.

Nor was this the only

expression of gratitude which the Prince’s justice and toleration called forth

from the poor oppressed guebres. One day, as, he himself informed me, on the

occasion of my farewell visit to his palace, he was riding abroad accompanied by

three servants only (for he loved not ostentation) when he met a party of

Zoroastrian women. Reining in his horse, he enquired how things went with them,

and whether they enjoyed comfort and safety. They, not knowing who he was, and

supposing him to be an ordinary Persian gentleman, replied that, though formerly

they had suffered much, now, by the blessing of God and the justice of the new

governor, they enjoyed perfect safety and security, and feared molestation from

none. Then they asked him to what part of the country he belonged; and he, when

he had fenced with them for a while, told them, to their astonishment and

confusion, who he was!

I was naturally anxious to see

some of the fire-temples, and finally, after repeated requests, a day was fixed

for visiting them. I was taken first, to the oldest temple, which was in a very

ruinous condition (the Muhammadans not suffering it to be repaired), and

presented little of interest save two tablets bearing Persian inscriptions, one

of which bore the date A.Y. 1009 as that of the completion of the tablet or the

temple, I know not which. Leaving this, we proceeded to a newer, larger, and

much more flourishing edifice, on entering which I saw, to my great delight, in

a room to the left of the passage of entry, the sacred fire burning bright on

its tripod, while around it two or three mudabs or fire-priests, with

veils covering their mouths and the lower part of their faces, droned their Zend

liturgies. These veils, as Ardashir informed me, are intended to obviate the

danger of the fire being polluted by the officiating priest coughing or spitting

upon it. ‘I was not, however, allowed to gaze upon this interesting spectacle

for more than a few moments, but was hurried on to a large and, well-carpeted

room in the interior of the building, looking out on a little courtyard planted

with pomegranate trees.. Here I was received by several of the fire-priests, who

regaled us with a delicious sherbet. The buildings surrounding the other three

sides of the courtyard were, as I was informed, devoted to educational purposes,

and serve as a school for the Zoroastrian children. This temple was built

comparatively recently by some of Ardashir's relatives, and on one of its walls

was the memorial tablet to his murdered brother Rashid.

Leaving this, we visited a

third temple, a portion of which serves as a theological college for the

training of youths destined for the priesthood, who, to some extent at least,

study Zend and Pahlavi; though I do not fancy that any high standard of

proficiency in the sacred languages is often attained by them. The space

allotted to these young theologians was not very ample, being, indeed, only a

sort of gallery at one end of the chief room. At the opposite end was spread a

carpet, on which a few chairs were set; and in a niche in the wall stood a

little vase containing sprigs of a plant not unlike privet which the dastur

called by a name I could not rightly catch, though it sounded to me like "nawa."

This plant, I was further informed, was used in certain of their religious

ceremonies, and “turned round the sun”; but concerning it, as well as sundry

other matters whereof I would fain have learned more, my guides showed a certain

reserve which I felt constrained to respect. Here also I was allowed a glimpse

of the sacred fire burning in a little chamber apart (whence came the odour of

ignited sandal-wood and the droning of Zend chants), and of the white-veiled

mubad who tended it. A picture of Zoroaster (taken, as Ardashir told me,

from an old sculpture at Balkh), and several inscriptions on the walls of the

large central room, were the only other points of interest presented by the

building.

On leaving this temple, which

is situated in the very centre of the "Gabr-Mahalla," or Zoroastrian

quarter, I was conducted to the house of Ardashir’s brother, Gudarz between rows

of Zoroastrian men and boys who had come out to gaze on the Firangi stranger. To

me the sight of these yellow-robed votaries of an old-world faith, which twelve

centuries of persecution and insult have not succeeded in uprooting from its

native soil, was at least as interesting as the sight of me can have been to

them, and I was much struck both by their decorous conduct and by the high,

average of their good looks. Their religion has prevented them from

intermarrying with Turks, Arabs, and other non-Aryans, and they consequently

represent the purest Persian type, which in physical beauty can hardly be

surpassed.

At the house of Ardashir's

brother, Gudarz, I met the chief-priest of the Zoroastrians, who was suffering

from gout, and a number of my host’s male relatives, with whom I stayed

conversing till 8.30 p.m., hospitably entertained with tea, wine, brandy, and

kebabs. Wine-drinking plays a great part in the daily life of the guebre;

but, though I suppose not one total abstainer could be found amongst them, I

never but once saw a Zoroastrian the worse for drink. With the Musulmans the

contrary holds good; when they drink, it is too often with the deliberate

intention of getting drunk, on the principle, I suppose, that "when the water

has gone over the head, what matters it whether it be a fathom or a hundred

fathoms?” To a Zoroastrian it is lawful to drink wine and spirits, but not to

exceed; to a Muhammadan the use and the abuse of alcohol are equally unlawful.

The Zoroastrian drinks because he likes the taste of the wine and the glow of

good fellowship which it produces; the Muhammadan, on the contrary, commonly

detests the taste of wine and spirits; and will, after each draught, make a

grimace expressive of disgust, rinse out his mouth, and eat a. lump of sugar;

what he enjoys is not drinking, but, being drunk, even as the

great mystical poet Jalau'd-Din Rumi says ---

“Nang-i-bang u khamr bar khud mi-nihi

Ta dam’ az khwishtan tu vd-rabi.”

"Tho u takest on thyself the shame of hemp and wine.

In order that thou may’st for one moment escape from thyself.”

The, drinking-cup (jam) used

at Yezd and Kirman is not a glass but a, little brass bowl. On the inside of

this the Zoroastrians often, have engraved the names of dead friends and

relatives, to whose memory they drink as the wine goes round with such formulae

as "Khuda pidarat biyamurzad" (“May God pardon thy father!”), "Khuda

madarat biyamurzad" (“May God pardon thy mother!"), "Khuda biyamurzad

hama-i-raftagan-ra"

(“May God pardon all the

departed! "). The following inscription from Ardashir's drinking-cup may suffice

as a specimen: ---

Mihraban ibn

Rustam-i-Bahram. Har kas kar farmayad 'Khuda biyamurzi' bi-Mihraban-i-Rustam, va

Sarvar-i-Ardashir, va Gulchihr-i-Mihraban bi-dahad: haftad pusht-i-ishan

amurzide bad! 1286 hijri."

“The wife of the beatified

Mihraban, the son of Rustam, [the son] of Bahram. Let every one who may make use

[of this cup] give a ‘Godpardon!’ to Mihraban [the son] of Rustam, and Sarvar

[the son] of Ardashir, and Gul-chihr [the daughter] of Mihraban: may they be

pardoned unto seventy generations! A.H. 1286.”

In drinking to the health of

companions the formula (used also by Muhammadans when they drink) is " Bi-salamati-i-shuma!"

(“To your health! "), the answer to which is "Nush-i-jan-bad!" (“May

it be sweet to your soul! “). I had ample opportunity of learning how to drink

wine “according to the rite of Zoroaster,” for almost every afternoon Ardashir,

accompanied either by Dastur Tir-andaz, or by his brother Gudarz, or by his

manager Bahman, or by other Zoroastrians, used to come to the garden and sit by

the little stream, which for a few hours only (for water is bought for a price

in Yezd) refreshed the drooping flowers. Then, unless Muhammadan or Babi

visitors chanced to be present, wine and 'arak were brought forth by old

Jamshid the gardener, or his little son Khusraw; fresh young cucumbers, and

other relishes, such as the Persian wine-drinker loves, were produced; and the

brass drinking-cups were drained again and again to the memories of the dead and

the healths of the living. It was on these occasions that conversation flowed

most freely, and that I learned most about the Zoroastrian religion and its

votaries. This is not the place to deal with the subject systematically, and I

shall confine myself to noticing a few matters which actually came under

discussion.

The Zoroastrian

year is solar, not lunar like the Muhammadan, and consists of twelve months of

thirty days each, and five additional days called gata (corresponding to the

Muhammadan "khamsa-i-mustaraka ") to bring the total up to 365. The year

begins at the vernal equinox, when the sun enters the sign of Aries (about 21st

March), and is inaugurated by the ancient national festival of the Nawruz,

or New Year’s Day, which, as has been already mentioned, i s observed no

less by the Muhammadans than by the Zoroastrians of Persia. Each day of the

month is presided over by an angel or archangel (of whom there are seven, called

Amshaspands, to each of which a day of the first week is allotted), save

that three days, the 8th, 15th, and 23rd of the month, are, ‘like the first,

sacred to Ormuzd. These are holy days, and are collectively known as the Si-dey.

The following is a list of the days of the month, each of which is called by the

name of the angel presiding over it:-(1) Ormazd; (2) Bahman, the

angel of flocks and herds; (3) Urdibihisht, the angel of light; (4)

Shahrivar, the angel of jewels, gold, and minerals; (5) Sipandarmaz,

the angel of the earth; (6) Khurdad, the angel of water and streams; (7)

Amurdad, the angel of trees and plants; (8) Dey-bi-Adhar, the

first of the Si-dey, sacred to Ormuzd; (9) Adhar; (1O) Abdn;

(11) Khir; (12) Mah; (13) Tir; (14) Gush; (15) Dey-bi-Mihr, the

second of the Si-dey; (16) Miht; (17) Surush; (18)

Rashn; (19) Farvardin; (20) Bahram; (21) Ram; (22) Ddd;

(23) Dey-di-Din in, the third of the Si-dey; (24) Din; (25)

Ard; (26) Ashtad; (27) Asman; (28) Zamyad; (29)

Muntra-sipand; (30) Anaram. Of these thirty names twelve belong also

to the months, as follows:--

|

SPRING (Bahar) |

SUMMER (Tabistan) |

|

I . Farvardin

2. Urdi-bihisht

3. Khurdad |

4. Tir

5. Amurdad

6 . Shahrivar |

|

AUTUMN (Pa'iz) |

WINTER (Zamistan) |

|

7. Mibr

8. Aban

9. Adhar |

10. Dey

11. Bahman

12. Sipandarmaz |

The week has no place in the

Zoroastrian calendar, with which, as I have elsewhere pointed out

(Traveller's Narrative,

vol. ii, p.

414, n.

I; and J.R.A.S. for 1889, p. 929), the arrangement of the solar year instituted

by the Babis presents many points of similarity which can hardly be regarded as

accidental. As an example of the very simple manner in which dates are expressed

according to the Zoroastrian calendar, I may quote the following lines from a

Persian poem occurring in a Zend-Pahlavi MS of the Vendidad of which I shall

have something more to say shortly:---

"Bi-ruz-i-Gush, u dar

mah-i-Amurdad

Sene nub-sad, digar bud haft u baftdd,

Zi fawt-i-Yazdijird-i-shahriyaran

Kuja bigzashte bud az ruzgaran,

Nivishtam nisf-i- Vendidad-i-avval

Rasanidam, bi-lutf-i-Hakk, bi-manzil."

“On the day of Gush (the 14th day), and in the

month of Amurdad (the 5th month),

When nine hundred years, and beyond that seven and seventy, From the death of

Yazdijird the king

Had passed of time, I wrote the first

half of the Vendidad, And brought it, by God’s grace, to conclusion.”

A little consideration will

show the reader that one day in each month will bear the same name as the month,

and will be under the protection of the same angel. Thus the nineteenth day of

the first month will be “the day of Farvardin in the month of Farvardin,” the

third day of the second month "the day of Urdi-bihisht in the month of

Urdi-bishisht," and so on. Such days are kept as festivals by the Zoroastrians.

The angel Rashn, who presides

over the eighteenth day of each month, corresponds, in some degree, to the

angels Munkar and Nakir in the Muhammadan system. On the fourth day after a

Zoroastrian dies this angel comes to him, and weighs in a balance his good and

his bad deeds. If the former are in excess, the departed is admitted into

paradise;’ if the latter, he is punished-so my Zoroastrian friends informed me

by being re-incarnated in this world for another period of probation which

re-incarnation is what is signified by the term "hell" (duzakh) 1. Paradise, in

like manner, was understood by my friends of Yezd in a spiritual sense as

indicating a state rather than a place. I shall not readily forget

an altercation on this subject which arose between the Dastur Tir-andaz and my

Muhammadan servant Haji Safar. The latter had, I think, provoked the dispute by

applying the term atash-parast ("fire-worshipper”) to the followers of

Zoroaster, or it had been otherwise introduced. The Dastur at once flashed out

in anger. "What ails you if we prostrate ourselves before the pure element of

fire,” said he, “when you Muhammadans grovel before a dirty black stone, and the

Christians bow down before the symbol of the cross? Our fire is, I should think,

at least as honourable and appropriate a kibla as these, and as for

worshipping it, we no more worship it than do you your symbols. And you

Muhammadans” (turning to Haji Safar) “have of all men least right to charge us

with holding a gross or material creed; you, whose conception of paradise is as

a garden flowing with streams of milk and wine and honey, and inhabited by fair

boys and languishing black-eyed maidens. Your idea of paradise, in short, is a

place where you will be able to indulge in those sensual pleasures which

constitute your highest happiness., I spit on such a paradise I " Haji Safar

cried out upon him for a blasphemer, and seemed disposed to go further, but I

bade him leave the room and learn to respect the religion of others if he

wished, them to respect his. Later on, when the Zoroastrians had gone, he

renewed the subject with me, remarking that the Dastur deserved to die for

having spoken such blasphemy; to which I replied that, though, I had no desire

to interfere with his conscience, or, in general, to hinder him in the discharge

of the duties imposed upon him by his religion, I must request him to put a

check upon his zeal in this matter, at least so long as he remained in my

service.

In general, however, I found

my Zoroastrian friends very tolerant and liberal in their views. Ardashir was

never tired of repeating that in one of their prayers they invoked the help of

“the good men of the seven regions" (khuban-i-haft kishvar), i.e. of the whole

world; and that they did not regard faith in their religion as essential to

salvation. Against the Arabs, indeed, I could see that they cherished a very

bitter hatred, which the Dastur at least was at little pains to conceal;

Kadisiyya and Hahavand were not forgotten; and, with but little exaggeration,

the words of warning addressed to the Arabs settled in Persia in the second

century of the hijra by Nasr ibn Seyyar, the Arab Governor of Khurasan,

might be applied to them:-

“Fa-man yakun 'an asli dinihimu,

Fa'inna dinahuma an yuktala'l-'Arabu."

“And should one question me as to the essence of their religion,

Verily their religion is that the Arabs should be slain.”

From these poor guebres,

however, I received more than one lesson in meekness and toleration. “Injustice

and harshness,” said Bahman to me one day, "are best met with submission and

patience, for thereby the hearts of enemies are softened, and they are often

converted into friends. An instance of this came within my own experience. One

day, as I was passing through the meydan, a young Muhammadan purposely

jostled me and then struck me, crying, ‘Out of the way, guebre!' Though angered

at this uncalled-for attack, I swallowed down my anger, and replied with a

smile, ‘Very well, just as you like.’ An old Seyyid who was near at hand, seeing

the wanton insolence of my tormentor, and my submission and patience, rebuked

him sharply, saying, ‘What harm had this poor man done to you that you should

strike and insult him?’ A quarrel arose between the two, and finally both were

taken before the Governor, who, on learning the truth of the matter, caused the

youth to be beaten. Now, had I in the, first instance given vent to my anger,

the Seyyid would certainly not have taken my part, every Musulman present would

have sided with his coreligionist against me, and I should probably have been

beaten instead of my adversary.”

On another occasion I had been

telling another of Ardashir's assistants named Iran about the Englishman at

Shiraz who had turned Muhammadan “I think he is sorry for it now,” I con-chided,

“for he has cut himself off from his own people, and is regarded with suspicion

or contempt by many of the Musulmans, who keep a sharp watch over him to see

that he punctually discharges all the duties laid upon him by the religion of

Islam. I wish him well out of it, and hope that he may succeed in his plan of

returning to his home and his aged mother; but I misdoubt it. I think he wished

to join himself to me and come here, that he might proceed homewards by way of

Mshhad; but I was not very desirous of his company.”

“It is quite true,” replied

Iran, “that a bad companion is worse than none, for, as Sa'di says, it is better

to go barefoot than, with tight shoes. Yet, if you will not take it amiss, would

you not do well, if you return to Shiraz, to take this man with you, and to

bring him, and if possible his Muhammadan wife also, to England? This would

assuredly be a good action: he would return t o the faith he has renounced, and

his wife also might become a Christian; they and their children after them would

be gained to your religion, and yours would be the merit. Often it happens that

one of us Zoroastrians, either through mere ignorance and heedlessness, or

because he is in love with a Muhammadan girl whom he cannot otherwise win,

renounces the faith of his fathers and embraces Islam. Such not un-frequently

repent of their action, and in this case we supply them with money to take them

to Bombay, ‘where they can return, without the danger which they would incur

here, to their former faith. Often their Muhammadan wives also adopt the

Zoroastrian religion, and thus a whole family is won over to our creed.”

“I was not aware,” I remarked,

“that it was possible under any circumstances for one not born a Zoroastrian to

become one. Do you consent to receive back a renegade after any lapse of time?”

“No,” answered Iran, “not

after six months or so; for if they remain Musulmans for longer than this, their

hearts are turned black and incurably infected by the law of Islam, and we

cannot then receive them back amongst us.”

Of the English, towards whom

they look as their natural protectors, the Persian Zoroastrians have a very high

opinion, though several of them, and especially Dastur Tir- ndaz, deplored the

supineness of the English Government, and the apathy with which it regards the

hands stretched out to it for help. "You do not realise,” said they, “what a

shield and protection the English name is, else you would surely not grudge it

to poor unfortunates for whom no one cares, and who in any time of disturbance

are liable to be killed or plundered without redress.” After my return to

England I, and I think Lieutenant Vaughan also, made certain representations to

the Foreign Office, which I believe were not ineffectual; for, as I subsequently

learned, a Zoroastrian had been appointed British Agent in Yezd. This was what

the Zoroastrians so earnestly desired, for they believed that the British flag

would protect their community even in times of the gravest danger.

Although the Zoroastrian women

do not veil their faces, and are not subjected to the restrictions imposed on

their Muhammadan sisters, I naturally saw but little of them. Twice, however,

parties of guebre girls came to the garden to gaze in amused wonder at the

Firangi stranger. Those composing the first party were, I believe, related to

Ardashir, and were accompanied by two men. The second party (introduced by old

Jamshid the gardener, who did the honours, and metaphorically stirred me up with

a long pole to exhibit me to better advantage) consisted of Young girls, one or

two of whom were extremely pretty. These conducted themselves less sedately,

and, to judge by their rippling , laughter, found no little amusement in the

spectacle.

Old Dastur Tir-andaz was to me

one of the most interesting, because one of the most thoroughgoing and least

sophisticated, of the Zoroastrians. He appeared to be in high favour with the

governor, Prince ‘Imadu’d-Dawla, from whom he was continually bringing messages

of goodwill to me. In three of the four visits which I paid to the Prince, he

bore me company, standing outside in the courtyard while I sat within. My first

visit Was paid the morning after I had received the lamb and the tray of

sweetmeats wherewith the Prince, on the representations of the Dastur, already

described, was graciously pleased to mark his sense of my “distinction.”

Accompanied by the Prince’s pishkhidmat, or page-in-waiting (an

intolerably conceited youth), and several farrashes, who had been sent to

form my escort, we walked to the Government House, which was situated at the

other end of the town, by the Arg or citadel. The Dastur, who walked by my side,

was greatly troubled, that I had not a horse orattendants of my own, and seemed

to think that my apparel (which, indeed, was somewhat the worse for wear) was

hardly equal to the occasion. As I preferred walking to riding, and as I had not

come to Yezd to see princes or to indulge in ostentatious parade, these

considerations did not affect me in the least, except that I was rather annoyed

by the persistence with, which the Dastur repeated to the Prince-Governor that I

had come chapar (by post-horses) from Shiraz with only such effects as

were absolutely necessary, and that a telegram must be sent to Shiraz to have my

baggage forwarded with all speed to Yezd. The Prince, however, was very good

natured, and treated me with the greatest kindness, enquiring especially as to

the books on philosophy: and mysticism which I had read and. bought. I mentioned

several, and he expressed high approval of the selection which. I had made,

especially 1 commending the lawa'ih of. Jami, Lahiji's Commentary on the

Gulshan-i-Raz, and Jami's Ashi'atu'l-Lama'at, or Commentary on the

LaMa’dt of 'Iraki. Of Haji Mulla Hadi's Asraru'l=Hikam, on the other

hand, he did not appear to have a very high opinion. He further questioned me as

to my plans for the future, and, on learning that I proposed to proceed to

Kirman, promised to give me a letter of recommendation to Prince Nasiru'd-Dawla

the governor of that place, and also, to my consternation, expressed his

intention of sending an escort with me. I was accompanied back to the garden by

the farrashes, to whom I had to give a present of two tumans

(about 13s.).

The Prince’s attentions,

though kindly meant, were in truth somewhat irksome. Two days after the visit

above described, he sent his conceited pishkhidmat to enquire after my

health, and to ask me whether I had need of anything, and when I intended to

visit a certain waterfall near the Shir-Kuh, which he declared I must certainly

see before quitting his territories. For the moment I escaped in polite

ambiguities; but two days later the pishkhidmat again came with a request

that, as Ramazan was close at hand, I would at once return with him to the

Government House, as the Prince wished to see me ere the fast, with the

derangement of ordinary business consequent on it, began. I had no resource but

to comply, and after giving the pishkhidmat tea, which he drank

critically, I again set out with him, the Dastur, and the inevitable

farrashes, for the Prince’s residence. On leaving the palace shortly before

sunset, the Dastur mysteriously asked me whether, if I were in no particular

hurry to get home, he might instruct the farrashes to take a more devious

route through the bazaars. I consented, without at first being able to divine

his object, which was no doubt to show the Musulmans of Yezd that I, the Firangi,

was held in honour by the Prince, and that he, the fire-priest, was on the most

friendly and intimate terms with me.

After this visit I enjoyed a

period of repose, for which, as I imagine, I was indebted to the fast of Ramazan.

The Zoroastrians, of course, like myself, were unaffected by this, and so was my

servant Haji Safar, who came to me on the eve of the fast, to know what his duty

in the matter might be, He explained that travelers were exempt from the

obligation of fasting, provided they made good the omission at some future date;

but that if I could promise to remain at Yezd for ten clear days of Ramazan, he

could fast for those ten days, postponing the remainder of his fast till some

more convenient time. It was of no use, he added, to begin fasting unless he

could reckon on ten consecutive days, a shorter period than this not entering

into computation. I declined to bind myself by, any, such promise (feeling

pretty sure that Haji Safar would not be sorry for an excuse to postpone the

period of privation till the season of short days), and so, though it was not

till Ramazan 13th that I actually quitted Yezd, he continued to pursue the

ordinary tenor of his life.

Amongst the minor annoyances

‘which served to remind me that even Yezd was not without its drawbacks, were

the periodical appearances in my room of scorpions and tarantulas, both of which

abound in the dry, sandy soil o f this, part of Persia. Of these noxious

animals, the latter were to me the more repulsive, from the horrible nimbleness

of their movements, the hideous half-transparent grayness of their, bodies, and

the hairiness of their legs and venomous mandibles. I had seen one or two in the

caravansaray where I first alighted, but, on removing to the clean and tidy

little house in Ardashir's garden, hoped that I had done with them. I was soon

undeceived, for as I sat at supper the day after my arrival, I saw to m y

disgust a very large one of singularly aggressive appearance sitting on the wall

about three feet above the, floor, I approached, it with a slipper, intending to

slay it, but it appeared to divine ‘my intentions, rushed up the wall and half

across the ceiling with incredible, speed, dropped at my feet, and made straight

for the window, ‘crossing in its course the pyramid of sweetmeats sent to me by

the Prince, over which its horny legs rattled with a loathsome clearness which

almost turned me sick. This habit of dropping from the ceiling is one of the

tarantula’s many unpleasant, characteristics, and the Persians (who call it

roteyl or khaye-gaz) believe that it can only bite while descending.

Its bite is generally said to be hardly less serious than that of the scorpion,

but Ardashir assured me that people were seldom bitten by it, and that he had

never known its wound prove fatal. The Yezdis, at all events, regarded its

presence with much more equanimity than I did, and the Kalantar, or mayor, of

the Zoroastrians displayed no alarm when a large specimen was observed sitting

on the ceiling almost exactly over his head. The Prince-Governor manifested

somewhat more disgust when a tarantula made its appearance in his reception-room

one evening when I had gone to visit him; but then he was not a Yazdi.

As regards scorpions, I killed

a small whitish one in my room shortly after I had missed my first tarantula, A

day or two afterwards old Jamshid the gardener brought me up another which he

had just killed in the garden, and seized the occasion to give me a sort of

lecture on noxious insects. The black wood-louse-like animal which I had slain

at Chah-Begi he declared to have been a "susmar" (though this word is

generally supposed to mean a lizard). Having discussed this, he touched briefly

on the tir-mar (earwig?), sad-pa (centipede), and hazar-pa

(milli-pede), concluding with the interesting statement that in every ant-hill

of the large black ants two large black scorpions live. I suggested that we

should dig up an ant-hill and see if it were so, but he declined to be a party

to any such undertaking, seeming to consider that such a procedure would be

in-very indifferent taste. “As long as the scorpions stay inside,” said he, “we

have no right to molest them, and to do so is to incur ill-luck.” So my

curiosity remained unsatisfied.

Old Jamshid was very

particular in the observance of his religious duties, and I constantly heard him

muttering his prayers under my window in that peculiar droning tone which so

impressed the Arabs that they invented a special word for it. Ardashir, who had

seen the world and imbibed latitudinarian ideas, affected to regard this

performance with a good-natured contempt, which he extended to many of the

Dastur's cherished convictions. One day, for instance, mention was made of

ghuls and. other supernatural beings. “Tush,” said Ardashir, "there are no

such things.” "No such things 1” exclaimed the Dastur, "why I have seen one

myself.” “No, no,” rejoined Ardashir, “you saw a man or a mule or some other,

animal in the gloaming, and, deceived by the half-light, the solitude, or your

own fears, supposed it to be a ghul.” Here I interposed, begging the

Dastur to narrate his experience, which he readily consented to do.

“I was riding back from Taft

to the city one evening,” said he, “when, nearly opposite our dakhme, I

lost my way. As I was casting about to discover the path, I suddenly saw a light

before me on the right. I thought it. must come from the village of kasim-abad,

and ‘was preparing, to make for it, when it suddenly shifted to my left hand and

began to approach me. It drew quite near; and then I saw a creature like a wild

pig, in front of which flitted a light like a, large lantern, I was horribly

frightened, but I repeated, a prayer’ out of the Desatir, whereupon the

thing vanished. It soon reappeared; however, this time in the form of a mule,

preceded by a man bearing a lantern, and. thus addressed me: ‘Ey adami-zad!

Inja che mi-kuni?' (‘O son of man! What dost thou here?’) I replied that I

had lost my way. Thereupon it pointed out a path, which, as it assured me, would

lead me to the city, I followed this path for some distance, but it only led me

farther out of my way, until at last I reached a village where I found some of

our own people. These set me in the right road, and would have borne me company

to the city, but I would not suffer them to do so, believing that I should have

no further difficulty. On reaching a bridge hard by the city, I again saw the

creature waiting for me by the roadside it again strove to mislead me, but this

time I paid no heed to it, and, pushing past it, reached my house in safety. Its

object was to lead me into some desolate spot and there destroy me, after the

manner of ghuls. After this experience you will understand that I am

firmly convinced of the existence of these creatures.”

I was not s o much troubled at

Yezd by applications for medical advice and treatment as I had feared, partly

because, after my experiences at Dihbid and God-i-Shirdan. I had for-bidden Haji

Safar and Baba Khan to say a word, about my having any medical knowledge, and

partly because Ardashir would not suffer strangers of whom he knew nothing to

come to his garden to see me. Once, however, when I was sitting talking to

Bahman and Iran in Ardashir's office (situated on the ground floor of one, o f

the chief. caravansaray in the city), a crowd of people assembled outside to

stare at me, from which a Seyyid presently disengaged himself, and asked me

whether 1 would cure him of an enlarged spleen. I asked him how he knew that it

was his spleen that I was affected. He replied that the Persian doctors had told

him so “what the Persian, doctors can diagnose, can they not treat?” I

enquired. “Yes, he replied,” they can, but they prescribe only two remedies,

sharab and zahrab, of which one is unlawful and the other

disgusting.” I finally told him that I could not undertake to treat him without

first examining him and that if he wished this he must come and see me in

Ardashir's garden, He never came, however; or, if he did, he was not admitted.

The Zoroastrians are, as a rule, good gardeners, and have some skill in the use

of simples. From Ardashir and his gardener, Jamshid, I learned the names and

supposed properties of many plants which grew in the garden. Unfortunately the

little botanical knowledge lever possessed had grown so rusty by long disuse

that often I was unable to supply the English name, or even to (refer the plant

to its proper order. However I give the following list as contributions towards

a better knowledge of the Persian nomenclature. Pudana or pudanak;

kasni, accounted “cool” and good for the liver; from it is prepared a

spirit called 'arak-i-kasni; turb (radish) ; gav-gush

(fighting-cock); aftab-gardan, or gul-i-khurshid (sunflower); bid-anjir,

or bid-angir (castor-oil plant) ; razdane (fennel), said to be an

analgesic; yunje (clover); tare, a small plant resembling, garlic

and with a similar smell, said to be good for haemorrhoids; shah-tare,

accounted “hot and moist” a decoction of it, taken in the morning on an empty

stomach, is said to be good for indigestion and disorders, of the stomach;

shavij, a “hot?” umbelliferous plant with a yellow blossom; gashnij,

a “cold” umbelliferous plant with a white flower; chughandar (beetroot) ;

gul-i-khatmi (holly-hock); kalam (cabbage), called by the guebres

in. their dialect kumni; isfinaj (spinach?); kahu (lettuce)

; kaduje (ragged-robin or campion ); karanfil (passion-flower).

I have alluded to the dialect

spoken amongst themselves by the Zoroastrians of Persia, and by them called

"Dari." This term, has been objected to by M. Clement Huart, who has

published in the Journal Asiatique several valuable papers on certain

Persian dialects, which he classes together under the name of “Pehlevi-Musulman,”

and regards as the descendants of the ancient Median language preserved to us in

the Avesta. The chief ground of his objection is that the description of the

Dari dialect given in the prolegomena of certain standard Persian dictionaries

does not at all agree with the so called Dari spoken by the guebres of Yezd and

Kirman. Personally I confess that I attach but little importance to the evidence

of the Persian lexicographers in this matter, seeing that it is the rarest thing

for an educated Persian to take any interest in local dialects or even to

recognise their philological importance and I shall 1 therefore continue

provisionally to call the dialect in question by the name given to it by those

who speak it. That it is closely allied to the. Kohrudi, Kashani, Sivandi, Luri,

and other dialects spoken in remote and isolated districts of Persia, and

generically termed by the Persians “Furs-i-kadim.” (“Old Persian”), is

however, not to be doubted.

This Dari dialect is only used

by the guebres amongst themselves, and all of them, so far as I know, speak

Persian as well. When they speak their own dialect, even a Yezdi Musulman cannot

understand what they are saying, or can only understand it very imperfectly. It

is for this reason that the Zoroastrians cherish their Dari, and are somewhat

unwilling to teach it to a stranger. I once remarked to Ardashir what a pity it

was that they did not commit it to writing. He replied that there had at one

time been some talk of translating the Gulistan into Dari, but that they

had decided that it was inexpedient to facilitate the acquisition of their idiom

to non-Zoroastrians. To me they were as a rule ready enough to impart

information about it; though when I tried to get old Jamshid the gardener to

tell me more about it, he excused himself, saying that knowledge of it could be

of no possible use to me.

The following is a list of the

Dari words and phrases which I collected at Yezd: ---

Hamushtudwaun,

to arise (shortened in speaking to hamushtun); imperative, hamusht;

present tense (1 sing.) hamushtude or hamushtudem; (2 sing.) (3

sing.) hamushtud, (1 plur.) Hamushtudim, (2 plur.)

hamushtudid, (3 plur.) hamudhtu-dand.

Wotwun, to say;

imperative, ve-va; past tense, am-nut, ud-vut or t'ad-vut,

osh-vut or inoshvut, (plur.) ma-vut or ma-ma-vut,

do-vut, sho-vut. Don’t talk = vuj khe ma-ku (kbe = khud, self; ma-ku =

makun, do not do or make).

Graftun, to

take; ashnuftan, to hear; didwun, to see; kushtwun, to

strike.

Venodwun,

to throw “Turn (lit. throw) the water into that channel,” “Wow de o ju ve-ven”

(wow = water; de = to, into; o = that).

Nashte or

nashtem, I sat; (2 sing.) nashti; (3 sing.) nasht; (1 plur.)

ma-nashtun Imperative (2 sing.) unik; (a plur.) unigit. Ve-shu, go;

ko'ishi, whither goest thou? Hamashtun va-shim, let us arise and go;

ma ve-shim, let us go. Ve-shu gau, go down; shuma gav-shit, do

you go down. Me-wu ve-she, I want to go.

Bi-yu, come;

mune u, come here; me byu i, may I come?

Omuda ve-bu, be

ready.

Wow,

water. Dumined, 'arak, spirit (so called, they say, because it

distils “from the end of the pipe,” dum-i-ney). Kilowel, wine (said to be

onomatopceic, from the noise it makes as it is poured out of the bottle). Wakt-i-kilowel

davarta, the time for wine has passed.

Gaff, talk;

gaff zadan, to talk. Bawz, a bee. Ruzhgarat nyak, good day.

Those who desire fuller

information about this interesting dialect, which well deserves a more careful

and systematic study than it has yet received, may consult General Houtum-Schindler's

admirable paper on the Zoroastrians of Persia (Die Parsen in Persien,

ihre Sprache, etc.) in vol. xxxvi of the Zeitschrift der Deutschen

Morgenlandischen Gesellschaft (pp. 5 4-88); Ferdinand Just's article in

vol., xxxv of the same periodical (pp. 327-414); Beresine’s Dialectes

Persanses (Kazan, I 85 3) ; and the articles of M. Huart in series viii of

the Journal Asiatique (vol. vi, p. 502; vol. xi; ‘p. 298 ; vol. xiv, p. 5

34):

In this connection I may also

cite a verse written in the Kashani dialect by a Kashi who wished to “take off "

the speech of his fellow-townsmen.

“Pas-khun u pish-khun ki

pur bafr bid

Sbubbe na-darad ki zameystun risid.

Kise-i-sahbun bi-tih-i-salt nih;

Bigh Zadand; nawbat-i-hammun risid.”

“Now that the front-yard

and back-yard are full of snow,

There is ‘no doubt that winter has come.

Put the soap-bag in the bottom of the basket (?);

They are blowing the horn; the time for the bath has come.”

While I am on the subject of

these linguistic curiosities, I may as well mention a method of secret

communication sometimes employed in Persia, the nature and applications of which

were explained to me by my, Erivani friend a few days before his departure for

Mashhad. Such of my readers as have studied. Arabic, Persian, Turkish, or

Hindustani will know that besides the ordinary arrangement of the letters of the

Arabic alphabet there is another arrangement called the "abjad" (from the four,

letters alif, ba, jim, dal which begin it) representing a much older order. The

order of the letters in the abjad is expressed by the following series of

meaningless words, consisting of groups of three or four letters each supplied

with vowel-points to render them pronounceable.:---abjad, hawaz, hoti, kalaman,

sa'fas, kara-shat, thakhadh (sakhadh) dadhagha (zazagha). In this order each has

a numerical value; alif = 1, ba = 2, jim = 3, dal = 4, and so on up to ya = 10;

then come the other tens, kaf = 20, lam = 30, and so on up to kaf = 100; then

the other hundreds up to gheyn = 1000. The manner in which, by means of this

abjad, words and sentences may be made to express dates is familiar to all

students of these languages, and I will therefore only give as a specimen, for

the benefit of the general reader, the rather ingenious chronogram for the death

of the poet Jami premising that he was a native of the province of Khurasan;

that “smoke” or “smoke of the heart” is a poetical term for sighs; and that to

“come up from” in the case of a number means to be subtracted from.

This, then, is the chronogram:

“Dud az Khurasan bar amad,” “Smoke (sighs) arose from Khurasan," or "dud (dal =

4, vav = 6, dal = 4; total 14) came up (i.e. was subtracted) from Khurasan" (kha

= boo, ra = 200, alif = I, sin = 60, alif = I, nun = 50; total 912). Taking 14

from 912 we get the date of Jami's death, A.H. 898 (= A.D. 1492).

The method of secret

communication above alluded to consists in indicating first the word of the

abjad in which the letter to be spelt out occurs, then its position in that

word. In communicating by raps, a double rap knocks off each word of the abjad,

while on reaching the word in which the desired letter occurs its position in

that word is indicated by the requisite number of single raps. An instance will

make this clearer. It is desired to ask, "Nam-i-tu

chist?"

(" What

is thy name?"): the letters which spell out, this message are -- nun, alif, mim,

ta, vav jim (for c h im), ya, sin, ta. Nun is in the fourth word of the abjad,

and is the fourth letter in that word (kalaman). It is therefore indicated by

three double raps (removing or knocking off the three first words,

abjad,

hawaz, hoti, and thus bringing us to the next word,

kalaman),

followed by four single raps (chowing that it is the fourth letter in

this word). The remaining letters are expressed in similar fashion, so that if

we represent double raps by dashes and single raps by dots, the whole message

will run as follows: ---…. (nun); .(alif); ---… (mim); -----…. (ta) -.. (vav);

... (chim or jim); -- … (ya); ----. (sin); ----- .... (ta).

Messages can be similarly

communicated by a person smoking the kalyan or water-pipe to his

accomplice or partner, without the knowledge of the uninitiated. In this case a

long pull at the pipe is substituted for the double rap, and a short pull for

the single rap. Pulling the, moustache, or stroking the neck, face, or collar

(right side for words, left side for letters) is also resorted to, to convert

the system from an auditory into a visual one. It is expressed in writing in a

similar fashion, each, letter: being represented by an upright stroke, with

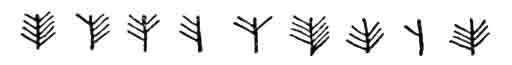

ascending branches on the right for the words and on the left for the letters.

This writing is called, from the appearance of the letters, khatt-i-sarvi

("cypress-writing?)

or khatt-i-shajari

(“tree-writing "). In this character (written, in the usual way, from right to

left) the sentence which we took above ("nam-i-tu chist?") will stand as

follows:--

The mention of enigmatical

writings reminds me of a matter which I omitted to speak of in its proper place

- I mean the Pahlavi and Zend manuscripts preserved ‘in the fire- temples of

Yezd. Although I knew that Yezd had long since been ransacked for such

treasures, and that, even should any old manuscripts remain, it would be

impossible to do more than examine them (a task which I, who knew no Pahlavi and

only the merest rudiments of Zend, was but little qualified to undertake), I

naturally did not omit to make enquiries on the subject of the Dastur and

Ardashir. As I expected, most of the manuscripts (especially the older and more

valuable ones) had been sent to the Parsees of Bombay, so as to be safe from the

outbursts of Muhammadan fanaticism to which the Zoroastrians of Yezd are always

liable; but in one of the fire-temples I was shown two manuscripts of the sacred

books,, the older of which was, by the ‘kind-ness of the Dastur, lent to me

during the remainder of my stay at Yezd, so that I was enabled to examine it

thoroughly.

This manuscript, a large

volume of 294 leaves, contained, so far as I could make out, the whole of the

Vendidad, with interspersed Pahlavi translation and commentary written in red,

the headings of t h e chapters being also: in red, and the Avesta text in black.

On f. I 5 8 was inscribed a Persian poem of fifty-nine couplets, wherein the

transcriber, Bahram, the son of Marzaban, the son of Feridun, the son of Bahram,

details the circumstances of his life and the considerations which ‘led him to

undertake the transcription of the sacred volume. From this it appeared that

when the aforesaid Bahram was thirteen years of age, his father,

Marzaban-i-Feridun, left his country (presumably Yezd), and, at the command of

the reigning king, settled in Kazvin. After a while he went to Khurasan, and

thence to Kirman, where he died at the age of fifty-seven. The death of his

father turned Bahram’s thoughts to his religion, which he began to study

diligently with all such as could teach him anything about it. At the age of

sixteen he seems to have transcribed the Yashts; and at the age of twenty ‘he

commenced the transcription of the Vendidad, of which he completed the first

half (as stated in the verses, cited on p. 413, supra), on the 14th day of the

month of Amurdad, A.Y. 977. On the page facing that whereon this poem is written

are inscribed the dates of the deaths of a number of Zoroastrians (belonging,

probably to the family of the transcriber), beginning with Bahram's father

Marzabani-Feridun, who died on the day of Varahram (Bahram), in the, month of

Farvardin, A.Y. 970. The last date is A.Y. 1069. The writing of the

manuscript is large, clear, and legible, and it bears throughout the signs of

careful work. One side of f.29 is occupied by a diagram indicating, I believe,

the successive positions in which the officiating priest or mubad must stand in

relation to the fire-altar while performing some of the ceremonies connected

with the homa-sacrifice. This sacred plant (the homa, or hum, as it is now

called) is found in the mountains about Yezd, but I could not succeed in

obtaining or even in seeing a specimen while I was there. After my return to,

Cambridge, however the Dastur kindly sent me some of the seeds and stalks of it

packed in a tin box. I gave some of the former to the Cambridge Botanical

Gardens. Unfortunately they did not grow up, but they were identified, by Mr.

Lynch, the curator, as a species of Epbedra.

Near the end of the volume I

found the following short prayer in Persian: “Shikast u zad bad

Ahriman-i-durvand-i-kaj, ava hama divan u drujan u jaduvan,” “Defeated and

smitten be Ahriman the outcast, the forward, with all the demons and fiends and

warlocks.” Some of the original leaves of the manuscript had been lost, and

replaced by new ones written in a bad hand on common white paper.

It is time, however, to leave

the Zoroastrians, and to say something of the Babis of Yezd, with whom also I

passed many pleasant and profitable hours. But this chapter has already grown so

long that what I have to say on this and some other matters had better form the

substance, of another.

|