|

|

In his royal proclamation Darius the Great

calls upon Ahura Mazda to bless his land and to deliver it from 3 ever

present menaces, ‘lies’, ‘external aggression,’ and ‘drought.’ Darius the

great realizing the importance of agriculture as a corner stone of

civilization and human progress focuses on promoting it throughout his

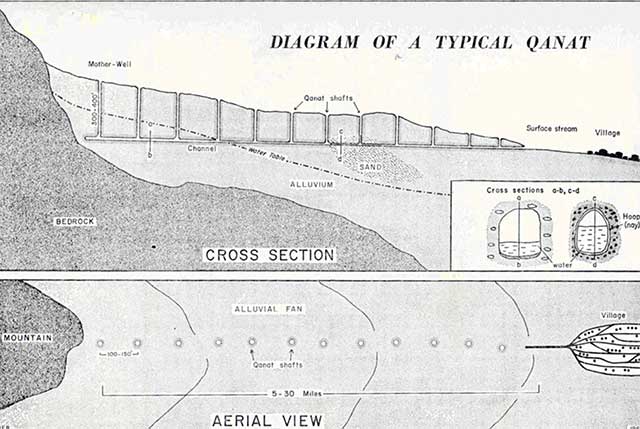

empire. A system of underground irrigation canals known as Qanat

is devised that is instrumental in turning the otherwise arid Iranian

plateau into the bread basket of the world. Borrowing the idea from

earlier civilizations - likely the Urartians - use of the similar system

of underground tunnels for mining, the Qanat allows tapped underground

water at the foot of mountains to flow and be delivered in the middle of

arid land often hundreds of miles away from its source, with minimum loss

to evaporation in hot desert like climate. The landscape of Eastern Near

East dotted with Qanats ever since that time bears witness to the

importance Zoroastrians and Iranians place on nurturing mother earth by

turning it green and keeping it fertile and agriculture rich.

[ii]

From the book, “City and Village in Iran –

Settlement and Economy in the Kerman Basin”, by Professor Paul W.

English, The university of Wisconsin Press, 1966

Darius and his successors were also

instrumental in having agricultural products native to one part of the

Empire planted in other parts helping diversify and improve local

agricultures. Alfalfa, abundant in Media (western Iran) was successfully

taken and planted in Greece to provide more nutritious forage for Persian

army there. The Persians introduced rice into Mesopotamia, pistachio into

Syria, sesame into Egypt.

The historians accompanying the invading army

of Alexander storming through Kerman province and central Iran report the

landscape being covered with forests and tall trees. Much of the same land

is now part of the Iranian desert. Negligence of agriculture in Post

Sassanian Iran resulting in deforestation has taken its toll on the land

that was once agriculture-rich and the envy of the world.

It is said few years after the fall of Iran to

Arabs in 7th century A.D., a member of the Sassanian royal

family was located and taken to the Arab ruler in shackles. Taking pity on

the man whose family’s fall from grace had given the Arab his prominence,

the new ruler asks him to name a reasonable favor to be granted to him. To

make the point for his ancestry, the captured Sassanian prince challenges

the Arab, ‘now that you are the overlord, ask your officials to travel the

length and width of this land and to find any vast stretch of earth that

is not green and fertile.’ ‘If such land is ever found, let me turn it

into fertile agricultural land.’

The Sasanians like the Parthians and the

Achaemdians before them valued and emphasized agriculture, and would

routinely reward the top producers.

In Islamic Iran, with most professional

opportunities denied to them, agriculture proved to be a viable means of

survival for many remaining Zarathushtis in Iran. Living in villages, and

away from cities that were fast becoming stronghold of Shia'ism by the

turn of the16th century many Zarathushtis were able to make a

living for themselves by cultivating the land. Some Zarathushtis of

Kerman forcedly moved to Isfahan by the Safavid Shah Abbas[iii]

were responsible in large part for the beautification of that city, the

lush gardens that earned the city the title ‘Isfahan, half the world’.

In the 18th and 19th

century for the Zoroastrians who were allowed to live in the cities of

Kerman or Yazd or the ones living in villages, fruit trees planted and

cared for in the house yards they had, served another practical use.

Often the access fruits born by the household trees or obtained elsewhere

would be dried in the court yards or on the roof tops and saved for use

during the winter months or for various religious functions and

gatherings. The grapes they grew would be used for making house wines for

family consumption on special occasions. A cup filled with wine would be

one of the item at Novruz table for Zoroastrian households.

Often the fruits grown by Zoroastrians and

villages had superior quality and would be prefaced by the title “Shah”

(Shah Miveheh, Shah Golabee – King pear, etc.).

Besides the fruits and the orchards that the

Zartoshty families grew in their homes, one tree that could be found in

most Zartoshty household was cypress (evergreen), the kind that grows in

Kerman and Yazd. The symbolism of the cypress of always staying green even

during the cold winter months - when other trees would lose their leaves -

must have had much to do with the Zoroastrian love affair with that tree.

Cypress’ longevity and its endurance under harsh natural conditions must

have also served as a source of inspiration to the Zarathushtis of Iran

enduring under very difficult conditions. Small branches of the cypress

would routinely be exchanged between Zoroastrians in Iran as a gesture of

good wishes on auspicious occasions.

With liberalization that came about in Iran in

the first part of the 20th century, the small remaining

community of Zoroastrians of Yazd and Kerman finding a more tolerant and

fair environment emerged as major agriculturalist well out of portion to

their small numbers.

Notably after the passage of 24 centuries

from the time of Darius the great whose Qanat systems had continued to be

in use, the pioneering of the new system of irrigation in 20th

century Iran was led by another visionary Zarathushti.

[iv]

[i]

This article was produced in July 2004 based on request from Dr. Sam

Kerr, guest editor of the Spring 2005 issue of the FEZANA journal,

under the theme ‘Vegetation on Earth’ for inclusion in that issue.

[ii]

Jim Hicks, “The Persians”, Time-Life Books, New York, 1975, pps.

77-82

[iii]

Ganj Ali Khan

[iv]

Esfandiar Bahram Yeganegi

|