|

The

Author: Mohammad Ibrahim Bastani

Parizi, a prolific Iranian writer, currently in retirement from his chairmanship

of the History Department of Tehran University was born in the village of Pariz

in the province of Kerman at the turn of the 20th century. Parizi undertook his initial schooling in

Pariz, Kerman city, and Tehran

before going to France to pursue his graduate studies leading to a doctorate

degree in History and literature from University of Paris.

Upon his return to his motherland and his appointment at the University

of Tehran, Bastani distinguished himself by his prolific writings and analysis

of historical events.

A

very humble man, Bastani has a unique style of writing that makes his books very

readable as he manages to analyze historical information filled with real life

experiences that gives the reader an interesting perspective of the historical

accounts he covers. A review of the

title of the books he has authored gives a perspective on his creative mind-set,

and his unique ability to personalize for the readers the otherwise academic

topics of his discourse. In one of

his books from Pariz to Paris, Bastani gives a very revealing account of his

experiences.

|

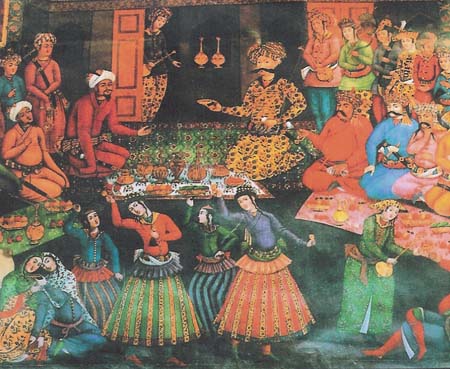

| From a painting at the ceiling of the

40-Column Palace in Isfahan, depicting Shah Abbas with his distinct long Mustache and his

courtiers being entertained by dancers while enjoying wine. The Safavids,

in strict accordance with religion decrees had banned alcoholic

drinks and the use of musical instruments for the general public.

However, as the painting shows the ban did not apply to them. |

In

addition to numerous articles he has published in Farsi and French in various

journals, Bastani has the authorship of 45 books in Farsi to his credit. Most of

his books have been re-published several times.

13 of his books are about the various aspects of history and geography of

Kerman amongst those one could mention, The prophet of the thieves (13

re-prints), History of Kerman (3 re-prints), Ganj Ali Khan (3 re-prints), The

records of Safavids in Kerman (1360 YZ release).

Eight of his books have titles revolving around the number 7, including

Goddess of the Seven Forts, The seven stoned mill, The seven layered bread, The

seven headed dragon, The seven bent Alley, Under the seven skies, The seven

layer Carved Stone, and The seven in Eight.

The remaining 24 books that he has published

covers a wide range of topics of interest in the history of post-Islamic

Iran.

Being

from Kerman, and having made the acquaintance of many Zarathushtis, Bastani

references the Zarathushtis in the context of a number of his books.

In so doing he goes further that many other non-Zarathushti Iranian writers

in acknowledging the contribution of this native minority and their plight in

post Islamic-Iran. However, he does

not go far enough in acknowledging all that befell the Zarathushtis in their

ancestral lands under the guise of religion. Bastani takes the view that the ugliness that befell the Zarathushtis was

an unfortunate reflection of the times past, and was commensurate with the

difficulties all Iranians faced. That

view, he reinforced in his last book “The Green-Clad old Sage”

published five years ago.

Although

Bastani fails to address the institutionalized atrocities committed against the Zarathushtis

in their ancestral land in the course of the past millennium, he

makes a few references in some of his books that conveys a sense of the scope

and severity of the calamity that befell this demised minority in their

ancestral land.

One

such account can be found in his book on Ganj Ali Khan written about the powerful

and influential governor of Kerman whose governorship coincided with the rule of

Shah Abbas, one of the most powerful rulers of the Safavid dynasty of Iran.

Historical

Perspective: The Safavid rule in Iran

from 1501 to 1723 A.D. was one of the longest continuous dynastic rule in the

post-Islamic Iran. It started off with the Zarathushtis in Iran still numbering

in millions, and by the end of their tenure that number had dwindled to less

than hundred thousand due to massacres, forced conversion and mass movements of

the followers of the ancient religion.

The

Safavids formalized Shia'ism as the state religion of Iran and used it as an

effective instrument of State. Besides Zarathushtis, the Sufis and other

religions minorities suffered persecution during this period.

Interestingly the Safavids had Sufi origin but embraced Shia'ism as an

effective instrument of

consolidating their hold on Iran that was surrounded by

Sunni dominance on all sides.

With Safavid power on the rise and despite its religious fervor, the

European powers were competing with each other for forming alliances with the

Safavids as an active way of keeping the Ottomans at Bay.

|

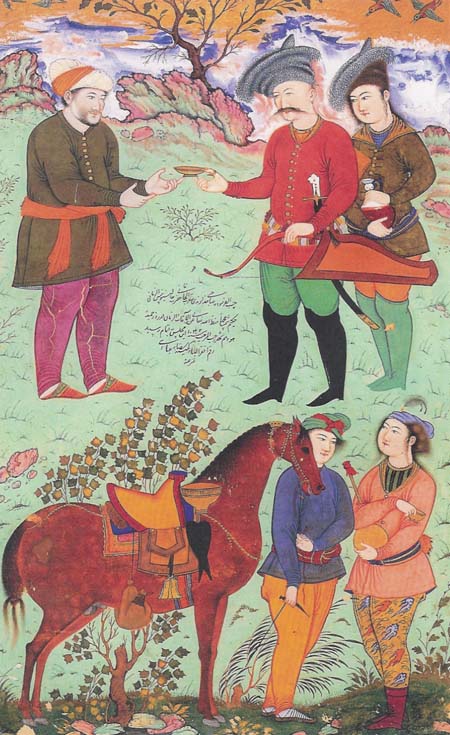

| A painting by

Riaz-i-Abbasi completed on January, 28, 1633, four years after Shah

Abbas's death, and currently on display at the

Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, Russia, shows Shah Abbas

passing a drink to Alam Khan after a hunting episode. |

In

the context of post-Islamic Iran, the Safavids earned the distinction of having

created the first centrally controlled Federal

system that brought all of Iran under one rule. Shah Abbas I’s rule from 1588

– 1629 saw the rise of the Safavid power to its peak due to his great

statesmanship. His rule coincided

with the expansion of European powers into Asia.

The Portuguese first excursion into Asia occurred as they landed on the

Persian Gulf coast of Iran and in Bahrain.

Although, Iran lacked naval forces, Shah Abbas forged an alliance with

the British, and enlisted the help of their naval forces to dislodge the

Portuguese from Persian Gulf, and that resulted in their sailing further East

and making their landing on the shores of India.

Shah Abbas also fought successful

wars against the Ottomans on the West and against the Uzbeks on the Northern

boundaries of Iran. European powers were in competition with each other to forge

alliances with the Safavids against the Ottomans.

An

avid hunter, with a taste for the finer things in life, Shah Abbas excelled in

using religion as an effective instrument of his rule.

The

Book: The book covers the rise and the historical events surrounding one of

the best known governors of Kerman in the post Islamic Iran.

The main Bazar and the oldest surviving public bath turned into museum in

Kerman bearing the name of that governor is a living testimony to the legacy of

that once powerful governor.

The

rise of that family to the position of influence is attributed to the first Ganj Ali

Khan, the patriarch of the family and the father of the famed governor.

It is believed that the first Ganj Ali Khan un-earthed what turned out to be a

small buried treasure. Putting his

precious find to good use, he was able to build the family fortune and leverage

it for his rise to a position of prominence in Kerman that warranted their

governorship appointment by the Safavid court looking for effective and

influential local chieftains who could have enforced Safavid authority over the

province.

In

his book, Bastani describes the events that unfolded during the long tenure of

the governor and the skills he brought to bear in dealing with them.

One event that Bastani makes a passing reference to is of great

historical significance to the Zarathushtis of Kerman.

This event eventually sealed the faith of that powerfull governor at the

hand of his patron in the capital

city of Isfahan, Shah Abbas. Although

Bastani’s motive in coverage of this event may have been for recording of

significant events, the accounting serves the purpose

of conveying the scope of the calamities that befell the Zarathushtis in

Iran during that period, the great injustices the political establishment

dispensed towards them, and the helplessness of that demised minority in facing

incredible odds.

The

rest of this book review is dedicated to the coverage of that event based mostly

from Bastani’s book. But for the sake of completeness information from other

sources is used so as to construct a complete accounting of the event.

Bastani

reporting of the episode is as follow.

1.

Two Zarathushti laborers being constantly harassed by their foreman got into a physical braw with the Moslem man

resulting in the death of the foreman. The

two Zarathushti man fearful of the grave retribution try to hide the body of the

dead foreman.

2.

The accidental death of the foreman is uncovered and the two guilty man

are reported to the office of the governor.

Ganj Ali Khan calls in the high Shia'ite Mullah of Kerman considered to be

the judge to make a ruling. The

high Mullah seeing this to be an opportunity to deal with the Zarathushtis in

Kerman finds the two Zarathushti guilty of killing a Moslem man, considered a high

crime.

3.

To render the punishment, he asks for a jar filled with honey

and a bag full of barley to be brought in his official quarters.

Under the watchful eye of all those present, he immerses his right hand

up to his wrist in the jar of honey until it is completely covered. Withdrawing his hand from the jar of honey, he

thrusts his hand into the bag of barley and leaves it immersed for a

short while. Then he withdraws his

hand, and asks the officials of his court to take an exact count of barley stuck

to his hand.

4

After the counting is completed, the Mullah declares that for every

barley counted, one Zarathushti person must be killed to avenge the death of the

Moslem foreman. The officials soon

realize there are not that many Zarathushtis in Kerman city to make up the exact

count. The judge orders that

additional Zarathushtis must be brought it from surrounding areas in the Kerman

province to make up the count.

5.

Ganj Ali

Khan endorses the ruling, and orders that public announcements to

be made across the provinces for all Zarathushtis to report to the provincial

capital city. A week’s timeframe

is set to allow the Zarathushtis in the far reaches of Kerman to arrive at the

site of their execution. The news

spreads across the city like wild fire.

6.

The next event unfolds in

Isfahan two nights later following the public announcements in Kerman.

Past mid-night, a sudden outcry from the Royal headquarter echoes across

the forty Column Palace, the official residence of the Safavids.

7.

Courtiers, including powerful Shia'ite high Ayatollahs of Iran associated

with the palace rush to the bedroom of Shah Abbas from where the outcry has

emanated. Shah Abbas with his

distinct long mustache, apparently shaken declares he had a horrible nightmare,

and saw half of Kerman city aflame.* The

courtiers tried to assure the king, that all is calm in Kerman according to an

official courier arriving back in the Capital the previous week. [*Shah Abbas, following the example of an earlier

Iranian ruler, Darius the Great, regularly dispatched personal spies to all

parts of the country with instruction to report back to him immediately in the

case of unusual events shaping up

in the provinces. It is reputed

that every night, he would secretly slip out of his palace in disguise and meet

his returning spies at pre-determined locations in the Isfahan Bazar.

The belief is that, as soon as the public execution announcement was made

in Kerman, one of Shah Abbas’s spies departed for Isfahan expediently and met

the King two nights later. Shah Abbas being careful not to alienate the Shia'ite

establishment by any appearance of sympathy towards the Zarathushti minority had

to stage that dramatic scene in his bedroom later that night.

8.

Shah Abbas rejects the claims and insists that something is eminent.

He declares to assure himself he must depart for Kerman city at the crack

of dawn to reach the province expediently.

The courtiers try to calm the King, but facing his persistence, depart to

make preparation for immediate departure.

9.

At the dawn hours, the Royal entourage departs in the direction of

Kerman, and reaches the outskirt of Kerman in record times.

10.

Within few miles of the entrance to the city, Shah Abbas stops and ask a

passing villager what is happening in Kerman.

With his entourage listening in, the old man reports, Ganj Ali Khan has

ordered all Zarathushtis to report in by the following day for a mass execution.

11.

At this point Shah Abbas declares if that is all, we can now return to

the Capital. [This is believed to have been a well calculated political move by

the King, in order not to appear to be sympathetic to the minorities.

12.

As they turn back, Shah Abbas calls one of his trusted officials for a

private audience, and hands him his Royal ring, the seal of Safavid authority.

He asks, his trusted official to gallop to Kerman city and hands the ring

to Ganj Ali Khan, and to inform the governor that the bearer of this ring

is passing by the city on his way back to Isfahan.

13.

Shah Abbas informs his entourage, they will return to Isfahan at a

leisurely pace since all seems to be in order.

14.

Back in Kerman city, Ganj Ali Khan receives the royal emissary, and on

recognizing the ring, declares that he will depart immediately to catch up with the Royal entourage in an attempt to invite

Shah Abbas to grace the city with his presence.

15.

A few hours later, Ganj Ali Khan has caught up with the Royal entourage,

and presents himself at the foot of King asking him to grace the city so the

Kermanis can show Shah Abbas the extent of their affection for him.

16.

Shah Abbas dismounts his horse, thanks the governor, and tells him

instead of hosting in Kerman, he should construct a Caravan Camping quarters at

that location they both stood. [Something

that Ganj Ali Khan orders immediately and dedicates to Shah Abbas upon

completion. The ruins of that

Caravan camping grounds stand to this day

17.

Shah Abbas asks Ganj Ali Khan to take a brief stroll with him and to

report on the condition of the province to him.

It is believed that once they were outside the hearing range of the rest

of the Royal entourage, Shah Abbas changes the subject, and asks about the

massacre that is about to unfold in Kerman city the next day.

Hearing the report, Shah Abbas must have instructed the governor to stop

the madness.

18.

As they walk back towards the waiting entourage, Shah Abbas embraces the

governor, wishing him well, and orders immediate departure for Isfahan.

19.

The rest is history. Ganj Ali

Khan on returning to Kerman city declares his previous decree on mass execution

of the Zarathushtis is cancelled. The

two Zarathushti laborers guilty of killing the Moslem foreman are hang in public

the following day. Ganj Ali Khan declares justices has been carried out.

20.

Less than a year later, a Royal courier arrives from Isfahan bearing a

decree to the governor of Kerman. It

is read in the presence of prominent Kermanis.

In thanking Ganj Ali Khan for his years of service and in recognition for

the same, the Royal decree informs Ganj Ali Khan that he has been appointed as

the new governor of Herat (part of present

Afghanistan prior to its split from Iran centuries later).

Those familiar with the political realities of Iran realized, this was a

serious reprimand for Ganj Ali Khan, and was in effect the downfall of his

career, and his fall from the hey day of his family fortune in Kerman.

21.

Years later, Shah Abbas orders the relocation of many of the Zarathushtis

of Kerman to Isfahan. [This move is believed to have been a measure by the Shah

to minimize similar risks to the Zarathushtis.]

The Zarathushti arrivals from Kerman mostly farm hands, are credited for

beautifying Isfahan, thereby justifying its reputation as one of lush cities in

Iran. The descendents of the same Zarathushti migrants from Kerman numbering more

than two hundred thousands were massacred a century later by the last of the

Safavids in an event that brought about his downfall as much as the event in

Kerman had brought about the downfall of Ganj Ali Khan a century earlier.

22.

In observance of Shah

Abbas’s intervention that saved the Zarathushtis of Kerman, an annual offering

(Aash-e-Shah Abbasi) dedicated to the memory of Shah Abbas has been held

continuously by the Zarathushti community of Kerman until the later part of the

twentieth century.

|