| Journal |

Taq-e

Bustan |

|

Series:

Visual Essays Author:

Jamshid Varza

(Slide

Show) |

On the road traveling

from Tehran toward the city of Kermanshah "Bakhtaran," one

reaches the ruins of Taq-e Bustan before entering the city of Kermanshah.

This magnificent historic site is located on the foot of a mountain

where a creek flows into a large pool of water feeding the surrounding

trees and shrubs.

Investiture:

It was customary for Sassanian Emperors to have their investiture carved

in a prominent location on a mountain side immortalizing events of their

reign. The images of investiture placed the king in the center,

receiving the promise of guardianship of the kingdom from a divinity

while under the protection of the second divinity. This image

immortalized the role and position of each king in the house of Sassan,

ruling Iran from AD 225-641 .

Sassanians practiced personification of

divinities in their Investiture carvings. This seems an approach unique to

Sassanian Kings.

During the second half of Sasanian

dynasty this ancient site was an important post on the silk road.

Sassanian Emperors up to Narseh had their investiture all carved in

their homeland, Pars in Naqsh-e Rostam, Tang-e Chogan, Haji-Abad or

other areas.

This magnificent site houses three Taqs

or investiture carvings. We shall walk you through each one starting

from the oldest. Investiture scenes have given scholars a window into

the rich world of Sassanian history and art.

|

|

Ardeshir II chose Taq-e-Bustan for the location of his investiture.

Perhaps this location, not very far from Bistun (or Bagestan) mountain,

had gained importance for being a important post on the silk road which

connected Persia to eastern Roman provinces.

|

|

In the center Ardeshir II is receiving the

diadem from Ahura Mazda on the right while under the protection of Mitra on

the left. Mitra is recognized by his rayed headdress stands on a large

lotus flower holding the saber of justice -- the barsom.

Beneath the feet of the great king lies the

slain enemy, apparently a Roman. Some scholars mentioned the possibility

of the fallen character being the image of defeated Ahriman.

|

|

Relief depicting Shahpur III (AD 383-388)

Perhaps the carvings of the central iwan (carved Taq) in Taq-e-Bustan was never finished. This Taq

shows Shahpur III who succeeded Ardeshir II standing next to his father

Shahpur II (AD 310-379), the great

Sassanian Emperor.

|

|

Close view of the central Taq shows only

images of Shahpur III and Shahpur II with no detailed decorations or any

investiture scene.

It is believed that Shahpur III legitimized

his reign by carving his image next to his great father, Shahpur II.

|

|

Investiture of Khosro II, Parviz (AD

590-628)

The larger iwan is the most majestic Sassanian investiture carving

surviving to date. The back wall is divided into two registers. The plan

indicates a triple majestic iwan which the third iwan (to the left) was

not constructed.

(The small dot on

lower-left corner is a man sitting in the arch's shade.)

|

|

The tympanum above represents the investiture

of the king receiving two diadems, one from Ahuramazda (right), the other

from protecting angel of waters, Anahita (left).

On the lower register is the equestrian

statue of the king, Khosro-II Parviz, wearing a coat of mail.

|

|

For this figure one might cite the description

of Ammianus Marcellinus (d.395AD):

"Moreover, all the companies clad in iron, and all parts of their

bodies were covered with thick plates, so fitted that the stiff joints

conformed with those of their limbs; and forms of the human faces were so skillfully

fitted to their heads, that since their entire bodies were covered with

metal, arrows that fell upon them could lodge only where they could see a

little through tiny openings opposite the pupil of the eye, or where

through the tips of their noses they were able to get a little

breath."

In another place Ammanius

says: "The Persians opposed us serried bands of mail-clad horsemen in

such close order that the gleam of moving bodies covered with closely

fitting plates of iron dazzled the eyes of those who looked upon them,

while the whole throng of horses was protected by coverings of

leather."

The figure of the horseman recalls the

knights of the Middle Ages of Europe. Despite the great difference in time

this visual relationship is not entirely accidental, since medieval

chivalry absorbed many Near Eastern traditions in the course of the

Crusades.

[1] Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman

general and historian served

in the army of Constantius II in Gaul and Persia. He fought against the

Persians under Julian the Apostate and took part in the retreat of his

successor, Jovian.

|

|

Image showing stone carvings on surrounding

walls and the main arch.

|

|

Close-up image of the guardian angel holding

the diadem above the main arch (left).

|

|

Detail of a scroll of flowers and acanthus

leaves carved on both sides of the facade of the iwan.

|

|

|

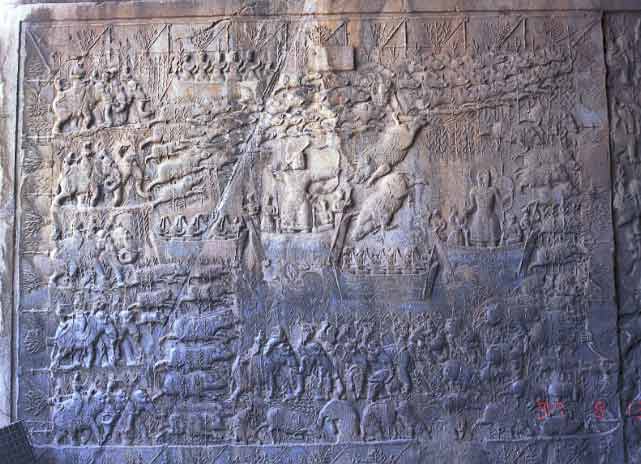

Boar hunting scene carved on interior right

wall of the Khosro II, Parviz's investiture Taq. This scene combines

two images of the king standing in a boat while targeting boars. This

carving carries a stunning level of detail.

|

|

Deer hunting scene carved on interior left

wall of the Khosro II, Parviz's investiture Taq. This scene combines

two images of the king riding and hunting deer. Each item in this image is

carved with a great degree of detail.

|

|

Ruins of a majestic building

Adjacent to three Taqs stands the ruins of a majestic building; stone made

ornaments carved in Sassanian style depict images of Investiture.

|

|

These building ornaments belong to a building

of immense importance which could be a palace or a memorial structure

celebrating the Investitures.

|

|

Fluted stone columns still remain in on site.

|

|

Sassanians were acquainted with the

practice of placing a relief or statue in a niche or a cave. The Sassanian

palace in Bishapur (near Kazerun) held sixty-four wall recesses for

holding statues.

Ruins of a large stone statue still stands

on the grounds adjacent to the Taqs.

|

|

Remains of building ornament with carved image

of Pahlavi inscriptions.

|

|

Large ceramic containers still standing on the

grounds; perhaps used for storage.

|

|

Stone caskets unearthed from nearby grounds.

Sassanians, as Zoroastrians did not pollute earth by burying

their dead thus placing them in caskets made of stone, ceramic or

practiced sky burial.

|