|

Series:

Library

Author:

Jackson, Abraham V. Williams

Subtopics:

Reference:

Related Articles:

Related Links:

|

'From Yezd's eternal Mansion of the

Fire.’

-- MOORE, Lalla Rookh.

Situated amid a sea of sand which

threatens to ingulf it, Yezd is a symbolic home for the isolated band of

Zoroastrians that still survives the surging waves of Islam that swept

over Persia with the Mohammedan conquest twelve hundred years ago.

Although exposed to persecution and often in danger from storms of

fanaticism, this isolated religious community, encouraged by the buoyant

hope characteristic of its faith, has been able to keep the sacred flame

of Ormazd alive and to preserve the ancient doctrines and religious rites

of its creed.

When the Arab hosts unfurled the green

banner with the crescent and swept over the land of Iran with cry of

Allah, shout of Mohammed, proclamation of the Koran, fire, sword,

slaughter, enforced conversion, or compulsory banishment, a mighty change

came over Persia. The battlegrounds of Kadisia and Nihavand decided not

Iran’s fate alone, but Iran’s faith. Ahura Mazda, Zarathushtra, and the

Avesta ceased almost to be known, the temple consecrated to fire became a

sacrifice to its own flame, and the gasp of the dying Magian's voice was

drowned by the call of the Muezzin to prayer on the top of the minaretted

mosque.

|

|

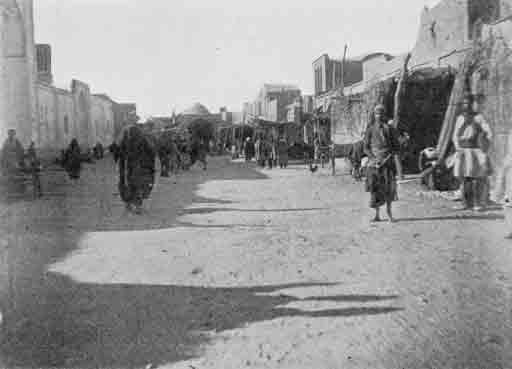

Scene in Yezd |

In a way the Moslem creed was easy of

acceptance for Persia, since Mohammed himself had adopted elements from

Zoroastrianism to unite with Jewish and Christian tenets in making up his

religion. The Persian, therefore, under show of reason or exercise of

force, could be led to exchange Ormazd for Allah, to acknowledge Mohammed,

instead of Zoroaster, as the true prophet of later days, and to accept the

Koran as the inspired word of God that supplanted the Avesta. The

conqueror’s sword, inscribed with holy texts in arabesques, contributed

its share, no doubt, to making all this possible, but many a Gabar

stubbornly refused to give up his belief, and consequently sealed his

faith with his blood. The few that sought religious liberty by accepting

exile in India became the ancestors of the modern Parsis of Bombay, so

often spoken of already; but the rest of the scanty handful that escaped

the perils of the Mohammedan conquest found a desert home at Yezd and in

the remote city of Kerman, not to mention the straggling few that are

found elsewhere in Persia, to prove the exception to the now universal

rule of Islam in Iran.

Almost immediately after my arrival at

Yezd I inquired for the home of Kalantar Dinyar Bahram, the head of the

Zoroastrian community, which numbers between 8000 and 8500 in the city and

its environs,[1]

but it took me some time to find his house. For nearly two hours my tired

mules and donkeys threaded their way through dusty, crooked lanes, across

camel filled squares, and in and out of closing bazaars, until we reached

the Kalantar’s door just as the sun was going down. The dwelling was

unpretentious on the outside, as all Persian houses are. Several servants

answered the summons of my man, who announced the arrival of a farangi,

and I was then ushered into a large, oblong room carpeted with fine

Persian rugs. The walls of the apartment were almost without decoration,

and the furnishing was confined chiefly to divans and cushions, as in many

Oriental dwellings; but on one side there were arranged in Occidental

manner a table and some chairs, made and upholstered after European

models. The front of the room seemed almost open to the air, because of

the broad doorways and deep windows that ran from floor to ceiling and

looked out upon a covered veranda and a court which enclosed a pretty

garden with roses and potted plants. My Gabar host entered the room a few

minutes later.

|

|

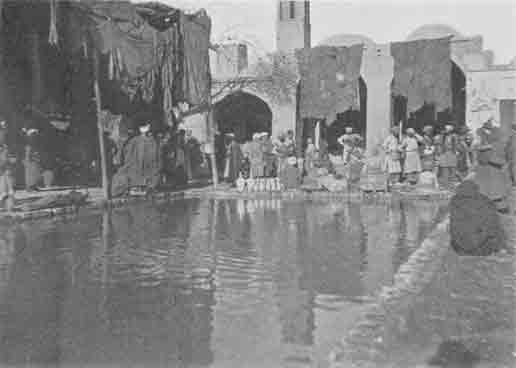

The Reservoir in the

Meidan at Yezd |

He was a man somewhat over fifty years of

age, with a roundish face and grizzled beard, and was dressed in a robe of

grayish cloth with a large white cotton sash about his waist. Upon his

head he wore the low rolled turban which is characteristic of the Persian

Zoroastrians; I had seen the same style of headgear worn by an Iranian

priest from Kerman when I was in Bombay. With genuine courtesy and

manifest cordiality my host extended a welcome, and turned aside with a

light touch the apologies I offered for my dusty appearance and for

entering his room wearing riding-leggings- as one has to do often in

Persia. In the best Farsi phrases that I could command I explained the

purpose of my visit. In Eastern fashion he immediately placed his house

and his all at my disposal, and this I found to be no empty phrase of

courtesy in his case, even though I could not accept the generous

invitation to lodge under his roof, because I had already promised to be

the guest of the English missionaries.

As soon as the Kalantar learned in more

detail the reason for my coming to Yezd, he sent for a member of the

community named Khodabakhsh Bahram Ra'is, who had studied in Bombay and

spoke English fluently, and who was known in Yezd as 'Master’ because of

his attainments. The style of dress of this scholar was similar to the

Kalantar's, even in the waistband and turban, and his features were of the

same general cast, although somewhat sharper. The nose, as in the case of

all the Persian Zoroastrians that I met, was rather prominent, but well

shaped. In manner he was modest and courtly, and his face lighted up when

he recognized the name he had heard from common friends in Bombay, where

my Zoroastrian interests were known. He held a hurried consultation with

the Kalantar, and they at once proposed a plan for a conference on the

morrow with the High Priest and with the spiritual and secular leaders of

the Zoroastrian community, setting the time in Persian fashion at so many

hours ‘after sunrise.’ Gifts of flowers were brought in and presented to

me as a sign of welcome, and the hospitality of supper was extended in

Zoroastrian style.

At this meal the host himself declined to

take a seat at the table, but moved about, standing now at the doorway and

again withdrawing to give directions, but returning to see them carried

out. He explained that this was regarded among his people as the true

manner of hospitality in olden times, when the master of the house was

supposed to be ever ready to serve his guests in person, and he thought

that I would best like to have the time-honored custom observed. The

number of dishes was perhaps ancient Median in its variety, rather than

early Persian -in other words, the abundance of Astyages and not the

frugality of his grandson Cyrus, if we may accept the picture in

Xenophon’s Greek romance as accurate. A hearty broth as first course mas

followed by lamb, vegetables, and some dishes characteristic of Yezd, with

sweetmeats and tea for dessert and some mild wine such as ‘ the house of

the Magian' produced in the days of Hafiz. To converse at table was, I

knew, contrary to the Avestan code, but I preferred not to observe this

prescription, even in the house of a Zoroastrian, as I wished to use every

possible moment to learn more concerning the interesting people among whom

I had come. We talked about matters of home life among the Zoroastrians,

the size of their community, their relations with Kerman and the

communication they had with their coreligionists in India, until i t was

time for me to leave for the English Mission, where I found a hearty

welcome awaiting me.

At an early hour the next morning I

returned again to the house of my Zoroastrian host. The Anjuman, or synod

of leading men in the Gabar community, was assembled to the number of

eighteen. The Chief Priest, Dastur-I Dasturan, who was named Namdar,

happened t o be absent in India at the time, but the Acting High Priest,

Tir Andaz, who was his father-in-law, was at home and entered the assembly

a few minutes later. He was a tall, handsome man, dressed in robes of pure

white, and his flowing beard of snow lent the dignity of age to his kindly

face. A brownish turban set off his dark, intelligent eyes, which had the

gleam of youth and were in keeping with his manly frame, erect bearing,

and clear voice.

The formal reception in Oriental manner

now began, and I was reminded of the description in the Zartusht Namah of

the ceremonies when Zoroaster first appeared before his patron Vishtaspa.

Settees and chairs mere placed in a large open hall that faced upon the

garden court. They were arranged in the form of a widespread V, in much

the same manner as in the council of Ormazd described in the old Iranian

Bundahishn.[2]

I was formally conducted to a seat a t the apex of this V. My host took

the place on the right, the High Priest sat on the left; the other members

of the assembly were arranged in order of seniority or rank. When all were

seated there was a moment’s pause. Then those sitting on the right turned

toward me and made a solemn bow, to which I responded; the same salutation

was formally repeated on the left. A servant next entered with a tray of

confectionery, a ewer of rose-water, and a hand-mirror. From the

hospitality of the Parsis in India, I was familiar with the rose-water and

sugar candy, but I had not previously seen the mirror used in ceremonies,

although I was told it was an old Zardushtian custom in receiving a guest.

My momentary embarrassment was relieved when the mirror wits handed to the

High Priest. He looked gravely into it, slowly stroked his white beard, on

which he poured a few drops of rose-water, and then with perfect dignity

passed the glass to the next, who did likewise, and so did the others. The

sugared bonbons, for which the Zoroastrians of Yezd are renowned, proved

very refreshing and served to satisfy that craving for sweets which is

felt by travelers in hot and dry climates. Meanwhile a number of the

company regaled themselves with snuff, as there seems t o be no objection

to the use of tobacco in that manner, but only to its being smoked, as

that is regarded as a defilement of the fire.

The formalities finished, the real

conference began, and for three or more hours I asked and answered

questions relating to Zoroaster and his faith, and concerning the

condition of his followers in Persia. Two manuscripts of the Avesta and

some fragments were first shown me. One of these was a fine large copy of

the Vendidad Sadah, seen by Professor E. G. Browne, when he visited Yezd

in 1888; the other was a text of the Yasna. The copy of the Vendidad Sadah

was much the older of the two, and was said to date back about three

hundred years. The Yasna manuscript belonged to the middle of the last

century. The third text, incomplete, was a good transcript of the Vishtasp

Yasht, which is a comparatively late compilation devoted to the praise of

Zoroaster's patron and other worthies of the religion. These were all the

manuscripts that could be produced at the moment, and the best-informed

members of the assembly stated that all their more important manuscripts

had been sent to India for safe-keeping or for use, and they feared that

the chances of obtaining hitherto unknown copies were growing yearly less.[3]

I urged upon them the importance of making a careful search, especially

among the older families, who might possibly have texts that had not found

their way to Bombay, and I have since corresponded with them on the

subject; but I am hardly more sanguine about the results of the search

than was Westergaard, who visited Yezd and Kerman in 1843.

[4]

The members of the assemblage naturally ascribed the loss of their texts

largely to the persecutions that followed after the Moslem conquest, an

instance of which I gathered from an oral tradition current among them. It

is worth repeating.

About a century and a half after the Arab

conquest, or more accurately in the year A.D.820, there was a Mohammedan

governor of Khorasan, named Tahir, who was the founder of the Taharid

dynasty and was called ‘the Ambidextrous' (Zu'l-Yaminein). He was a

bigoted tyrant, and his fanaticism against the Zoroastrians and their

scriptures knew no bounds. A Musulman who was originally descended from a

Zoroastrian family made an attempt to reform him and laid before him a

copy of the book of good counsel, Andarz-I Buzurg-Mihr, named from the

precepts given by Buzurg-Mihr, the prime minister of Anushirvan the Just,

and he asked the governor for permission to translate it into Arabic for

his royal master’sedification.[5]

Tahir exclaimed, 'Do books of the Magians still exist?’ On receiving an

affirmative answer, he issued an edict that every Zoroastrian should bring

to him a man (about fourteen pounds) of Zoroastrian and Parsi books, in

order that all these books might be burned, and he concluded his mandate

with the order that any one who disobeyed should be put to death. As my

informant added, it may well be imagined how many Zoroastrians thus lost

their lives, and what a number of valuable works were lost to the world

through this catastrophe. A variation of the story, but told of Tahir’s

son, named Abdullah (A.D. 828-840), and applied to the romance of Vamik

and 'Adhra,which is described in its title as ' a pleasing story (khub

hikayat) compiled by sages and dedicated to King Anushirvan ' (A.D.

531-579), is given by the Persian biographer Daulatshah in his literary

notices.' The story as it exists today among the Zoroastrians is an

interesting illustration of their pertinacity in keeping up the tradition

regarding the loss of much of their literature after the Mohammedan

conquest as well as during the invasion of ' Alexander the Accursed.'[6]

Inquiries regarding legends of Zoroaster

did not result in bringing out anything particularly new, but it was

interesting to obtain their views on some of the debated questions in

connection with the prophet's life. Zoroaster, they believe, came from Rei,

the ancient ruined city of Ragha near Teheran, long associated with his

mother's name.[7]

They knew nothing of the tradition that connects him with Urumiah.[8]

They associate his home, or rather his father's house, which is said in

the Vendidad to have been located on the Drejya, Darejya, or Daraj, with

the region about the river Karaj on the road from Teheran to Kazvin. The

village, they said, corresponds to the modern Kalak near the Karaj River

which flows from the mountain Paitizbara, as they interpret the words

puiti zaaruhi in the Avestan text.[9]

The resemblance between the letters D and K in Avestan Darejya, Drejya,

Phl. Dareji, Pers. Daraj, if written in the ancient script, does make this

ingenious comparison seem plausible for a moment, especially as the river

Karaj itself, a photograph of which I took three weeks later when I

crossed it, also shows precipitous banks that would answer to the

conditions supposed to be required by the phrase paiti zbarahi in the

Vendidad;

[10]

but in spite of this the identification seems fanciful, and I have given

reasons elsewhere for believing that the river Darejya, Drejya of the

Avesta, is the modern Daryai in Azarbaijan.[11]

I may add in passing that a number of persons in the assembly knew that

Zoroaster’s name was associated by tradition with the city of Balkh in

eastern Iran.

|

|

The Zoroastrian

Anjuman at Yezd |

For Zoroaster’s name, which appears in

the Avesta as Zarathushtra and in Modern Persian as Zartuaht or Zarduaht,

which is believed in reality to mean some sort of a camel (Bv. ushtra, see

p. 89, above) they offered nearly a dozen fantastical interpretations or

attempted etymologies. Dastur Tir Andaz, after the Oriental manner,

suggested that the name, if divided as Zartusht, might be explained as

‘pure gold,’ or ‘washed gold,’ as if the latter element were connected

with shustan, ‘to wash.’ Another member of the company proposed ‘enemy of

gold,’ as if the final member of Zar-duaht were dushman, ‘foe.’ Finally my

host turned to the lithographed book that he held in his hand, and which

seemed to be a compendium of the various Persian and Arabic writers who

mention Zoroaster and are already known to Western scholars.

[12]

The work contained no less than nine different explanations, part of them

cited from Persian lexicographical works, and I subsequently learned that

it was handed down by Farzanah Bahram ibn Farhad, a disciple of Azar

Keivan, who lived in the time of Akbar the Great, about A.D. 1600.

[13]

The value of the book was most highly thought of by my best informed

critic, Khodabakhsh Ra’is, who referred to it as an imaginative work and

branded the etymologies as ‘ fanciful and invented by the disciples of the

aforesaid Azar Keivan, who was a half-Brahman, half-Zoroastrian, a

believer in metempsychosis.’ Scholars will certainly agree with the

estimate as to the philological value of the interpretations, but I give

the list as I noted it.

1. afraid-i

avval, ‘first created being.’

2. nafs-i kull,

‘universal soul.’

3. nufs-i natikah, ‘spirit of speech.’

4. ‘akl-i falak-i ‘utarid,

‘genius of the heaven of the planet Mercury?

5. nur-i mujarrad,

‘incorporeal light.’

6. ‘akl-i fa‘‘al,

‘active genius.’

7. rabbu ’n-nau’-i insan,

‘lord of all mankind.’

8. rast-gu,

‘ truth-speaker.‘

9. nur-i khuda,

or

nur-i yazdan, ‘light of God.’

From the same historical compilation the

reader cited a passage to the effect that the Mohammedans believed that

there mere several Zoroasters - a view which I had heard propounded also

by some of the Zoroastrians in India-and that the Zardusht of Vishtasp’s

time was the ninth in order, the first of them being Hoshang;

[14]

but this view, according to my host, was due to a mistaken reading of a

verse in the Shah Namah.

Prom questions relating to Zoroaster we

turned to religion and philosophy. The discussion led to the problem of

dualism, the relation of Ormazd (Ahura Mazda, ‘Lord Wisdom’) and the

archangels and angels (Amesha Spentas and Yazatas) to Ahriman (Angra

Mainyu, ‘Evil Spirit,’) and the arch-fiends and fiends (Daevas and Drujes),

who war against the soul of man. I found that the most enlightened of

these Zoroastrians look upon Ahura Mazda as comprising within himself the

conflicting powers of good and evil, designated respectively as Spenta

Mainyu, ‘Holy Spirit,‘ and Angra Mainyu, ‘Evil Spirit,’ and that their

views in this respect, and possibly under the influence of Bombay, mould

agree with the monotheistic tenets upheld by the Parsis of India to-day,

who stoutly deny the allegation that Zoroastrianism teaches pure dualism.[15]

They believe also in the resurrection of the dead, or are acquainted, at

least, with this doctrine, which their faith has taught since early times;

and my informant promptly gave me the technical term (Pahlavi ristikhiz,

Mod. Pers. ristakhiz) for the ‘rising of the dead.’ The Messianic doctrine

of a Saoshyant, or Savior, appeared likewise to be well known.

When hearing the High Priest recite

passages from the Avesta and when listening to a Mobed as well as a layman

read from the sacred texts lying before us, I was struck by certain

peculiarities of pronunciation that are worthy of note. For some of the

striking features I was prepared through a previous study of the

variations in the Iranian manuscripts of the Avesta, used by Geldner for

his great edition of the Avesta, and through my observation of the

pronunciation of the Parsi priests in India;

[16]

but some of the peculiarities and certain phonetic inconsistencies in

reproducing the words were quite unexpected. What I noticed most was the

fact that the Avestan letters th, ph, dh, gh, and generally kh, which are

presumed historically to have been spirants, as in English kith, hurthen

(for burden), and German hoch, were pronounced as ordinary t, d, g, k, or

occasionally as aspirates t, d. g, k, (t, dh, gh, kh): for example, atha,

‘so,’ sounded as ata or at‘a atha; veretraghna, ‘Victory.’ The consonant t

was given everywhere as d; for example, cvat: ‘as many as,’ was pronounced

like chwad. The secondary nasal nh (&) arising in Avestan from an original

sibilant was pronounced like nk (vank-e-osh, vank-hi-osh, or vank-i-ash,

for vanheush, ‘of good,’ and ank-i-ash for anheush, ‘of the world’). The

voiced sibilant z was pronounced like the English z, and the Avestan

letter for zh could not be distinguished from our j (or from j, jh), while

the previously mentioned th occasionally interchanged with s, as in the

Avestan manuscripts (serish for thrish, ‘thrice’), thus coming near to the

earlier spirant character of the sound th than does the pronunciation t or

th in vogue among the priests as indicated above. The vowels a, o, u, were

frequently confused with each other, and i was shaded in the directiou of

e (veheshta, ‘best,’ for vahishta), while certain of the diphthongs were

merged into simple vowels (ao in mraot, ‘he spoke,’ pronounced as u, mrud).

The anaptyctic and epenthetic vowels were clearly marked: thus, pa-i-ti,

‘against.’

A few illustrations of the general

characteristics of the pronunciation will suffice. The name of the prophet

Zoroaster, in the nominative form Zarathushtra, was pronounced its

Zarat(h)ushtra, Zarat(h)oshtra, or even Zarat(h)ashtru. The opening lines

of the well-known Profession of Faith, naismi daevo fravarane mazdayasnu

zarathuushtrish vidivu ahura-d-kishu, ‘I abjure being a Demon- Worshipper,

I profess myself a Worshipper of Mazda, a foe to the demons, and a

believer in the faith of Ahura, ’were sounded like‘ naismi divu fravarane

mazdayasnu vidivu ahura-d-kishu.’ The sacred formula of the Ahuna Vairya

sounded on their lips quite different from the pronunciation generally

given to it in the Occident, at least as indicated in the accepted

philological works. This will be clear from a comparative transcript,

first in the ordinary transliteration with which we are familiar, and then

in the transliteration reproduced from the memoranda I made of the Yezd

pronunciation, supplemented by notes from Master Khodabakhsh.

AHUNA VAIRYA STANZA AS ORDINARILY WRITTEN

yatha ahu vairyu atha ratush ashatchit;

hacha

vangheush dazda mananho shyaothananam anheush mazdzai

khshathremcha ahurai a yim dregubyu dadat vastarem[17]

AHUNA VAIRYA STANZA AS PRONOUNCED AT YEZD

(with the variant pronunciations in

parentheses)

yata (yat‘a) ahi vaireyu ata (atha) ratosh (ratash) ashadcdid hachu

vank-e-osh (vanke-hi-osh, vanh-i-ash) dazda manankahu she-yu-tananume

anke-hi-osh (ank-i-ash) mazdae

kashatrumcha (khashatremcha) ahorue (aharae or ahurae) a yem dare-

gabe-yu (dargabyu) dadad vas-e-tarem (vawstarem)[18]

|

|

Two Zoroastrian

Priests at Yezd |

For a fuller collection of material to

illustrate the pronunciation I must refer to a monograph on the subject

which I hope soon to publish in one of the Oriental journals. While on the

subject of pronunciation and the reading of the sacred texts, I may add an

observation which will not, however, surprise specialists; I refer to the

fact that the Acting High Priest and also the more scholarly members of

the assembly were unaware that a great part of the Younger Avesta is

composed in metre. The idea of verse and verse-structure appeared wholly

new to them, when I read for them a portion of the Hom Yasht metrically in

the manner that is familiar to students in the West. In all such matters

it is manifest that ages of persecution and of neglect of their sacred

lore have not been without a detrimental influence upon their technical

knowledge; on the other hand, certain points in their pronunciation appear

to deserve the consideration of linguistic scholars, because the Persian

Zoroastrians are not affected by any philological bias and have remained

practically free from the Indian influences that may have affected, in

some respects, the pronunciation of the Parsis of Bombay.[19]

By this time it was considerably past mid-day, and nearly an hour more was

spent in examining the manuscripts and in photographing specimens of the

text. A rare privilege was now accorded me; I was invited by Tir Andaz to

visit his fire temple early that afternoon after I had enjoyed the repast

spread by our host. I was glad to accept at once this opportunity to

become acquainted with a place of worship used by the Persian

Zoroastrians. It was the temple of the Atash-I Varahram, or Atash Bahram,

'Fire of Victory,' situated in the Parsi quarter and located next to the

house of Dastur Namdar, the priest who was absent in India a t the moment.

It is the chief Zoroastrian sanctuary of Yezd, although there are three

other fire-shrines o r chapels, designated either as Dar-i Mihr or Adarian

besides one such minor place of worship in every Zoroastrian village in

the vicinity of the city.[20]

Upon reaching the temple I found it to be

simple, unpretentious building. From its exterior and from the entrance it

would hardly have been possible to recognize it as a temple a tall.

Mohammedanism allows no rivals to its beautiful mosques with turquoise

domes, arabesque arches, and slender tessellated minarets. The splendor of

the ancient temple of Anaitis at Ecbatana, from which, as I have described

above, conquerors carried off untold wealth in gold and silver plate, the

grand ruins of Kangavar and the gorgeous display at the Shrine of Fire in

Shiz, under the Sasanian kings, belong to ages long since dead.[21]

|

|

A Wind Tower at Yezd |

Before reaching the main room of the

sanctuary at Yezd it was necessary to pass through several corridors and

an antechamber, all of which help to render the shrine safer from

desecration. On one side of the last passageway I observed a pile of short

logs, one or two feet long and several inches thick, that were used as

fuel for the holy flame;[22]

it appeared to be ‘well dried and well examined wood,’ as the Avesta

enjoins.[23]

From the anteroom I entered the large oblong chamber, or chapel, adjoining

the sanctum sanctorum in which the fire was kept. My ear caught at once

the voice of the white-robed priests who were chanting in the presence of

the sacred element a hymn of praise sung by Zoroaster of old. It was a

glorification of Verethraghna, the Angel of Victory, in the Bahram Yasht,

and I felt a thrill as I heard the Avestan verses –verethraghnem

ahuradhatem yazamaide, “we worship the Angel of Victory, created by

Ahura’-- ring out from behind the walled recess where the fire was hidden.

The door was open and I stood within a few feet of the fire, so as to

listen, but I made no attempt to see the flame, as I knew such a step

would be regarded as a profanation and might bar the way to other

privileges which I wished to enjoy. It seemed an unusual experience thus

to be standing in a fire-temple in Zoroaster’s own land and listening to

the priests of his hereditary line chanting verses from the sacred texts

as had been done for nearly three thousand years. The voice of the zot, or

officiating priest, was high, nasal, and resonant, and his intonation was

so rapid that he had to pause at times to catch his breath ; while his

assistant, the raspi, chanted in a lower key or accompanied his recitation

in a nasal minor key with great rapidity of utterance.[24]

Each of the celebrants wore over his mouth the paitidana, a small white

veil prescribed by the Avesta to be worn over the lips when before the

fire, in order to prevent the breath and spittle from defiling the

hallowed flame.

I almost fell into a revery as I listened

to this monotonous chanting of the Yasht; but the hymn was soon ended, and

the veiled priests came out from the presence of the fire and were kind

enough to allow me to take their photograph, although the light was too

dim to secure a good picture.

While speaking of pictures I may mention

a so-called portrait of Zoroaster hanging on the wall of this main

chamber. I had heard of it a number of years before, and when writing my

book on the Prophet of Ancient Iran I had expressed a keen desire to see

it.[25]

My conference with Tir Andaz in the forenoon, when he gave me the meager

information that he had about its possible remote connection with Balkh,

had prepared me for disappointment as to its value, but I did not expect

to find it of so little importance. The picture is merely a modern colored

print, apparently a cheap Parsi chromolithograph from India, perhaps not

twenty years old, and of no historic interest. It is a variety of the

familiar representation based on the Tak-I Bostan sculpture;[26]

but the-staff is not fluted, as in the sculpture, the top is capped with

a symbolic flame, as in other modern representations current among the

Parsis in India, and the lower end of the staff rests upon the ground.

This colored picture was the only decoration I noticed on the bare,

whitewashed walls.

At the rear of the chamber there was a

gallery used on occasions when a considerable number of the Zardushtian

community come together, as at the Gahanbar season, the Farvadin festival,

on some commemorative day, or at some special celebration. The gatherings

on such occasions are the nearest approach that the Zoroastrians have to

the assembling of a congregation in church, for they have nothing that

corresponds precisely to our general Sunday worship.

The Acting High Priest now opened a door

leading into a small side-chamber to the right of the sanctum where the

fire was kept. It was a room arranged as an Izashnah Gah, a place set apart for the performance of religious

ceremonies and priestly rites. The floor was built of stone and was

cemented and marked off into little channels (pavi) or grooves (kash), to

enclose the space within which the priest sat while conducting the ritual,

as I had witnessed in the halls adjoining the Parsi temples in India.[27]

A lambskin, used apparently as a seat, was lying on the floor, and there

were small, low stone stools such as are generally employed in the

Izashnah Gah, besides a number of sacrificial utensils. Among the latter

were the cups for holding consecrated water, milk, and the juice of the

hom plant (Av. haoma), from which the sacred drink was prepared in ancient

times, as nowadays, and partaken of by the priest as a part of the

ceremony.

The haoma, as is well known, corresponds

to the soma of Vedic India, which grows on the mountains,[28]

and the two branches which the priest gave me came from the mountain

heights some distance from Yezd. In addition to this and the urvaru

hadhanaepata, or pomegranate,[29]

there is still another plant employed in the sacrifice, and it has been

used in the Magian ritual since time immemorial. It is the barsom (Av.

baresman), the twigs or sprays of which are tied in a bundle at a certain

point in the sacrifice, corresponding in a distant manner to the barhis,

or straw, strewn as a seat for the divinities in the Vedic ceremonies of

old. In Yezd the tamarisk bush is used to form this bundle, and it is

bound with a slender strip of bark from the mulberry tree, probably in exactly

the same manner as it was in Zoroaster’s day.[30]

Brass rods are sometimes substituted for the twigs, as is done by the

Parsis in India, but at Yezd this substitution is made only in winter,

when it is impossible to procure the branches, or at some particular time

when it is impracticable to obtain them. It was the use of these very

branches, perhaps, that the Prophet Ezekiel denounced as an abomination to

God when he saw in a vision ‘about five and twenty men, with their backs

toward the temple of the Lord, and their faces toward the east, and they

worshipped the sun toward the east,… and, lo, they put the branch to their

nose.[31]

I saw the large tamarisk bush from which

the sprays mere cut for use in the barsom ceremony; it was of a light

green color, twelve or fifteen feet high, and stood in the garden

adjoining the rear of the temple. A high wall shut in the garden at the

back; a gallery ran part of the way around the enclosure; a flight of

steep steps led down from this to the ground, where there were blossoming

rose bushes, sweet scented shrubs and plants, a pomegranate tree, and the

tamarisk bush. Tir Andaz cut off from this three handsome sprigs, each

nearly two feet long, and presented them to me. They were slender and

delicate, covered with downy fibrous leaves, and look graceful even in the

dried form in which I now have them.[32]

Besides the sacred plants, perfumes (baodhi),

bread-offerings (draonah, myazda), consecrated water, the haotna, and

milk, the Avesta frequently refers to the cow (gao) in connection with the

Yasna ceremony. Like their Parsi brethren in India, the Zoroastrians of

Persia interpret the Avestan words gao jivya, lit. ‘iving cow,’ as goat’s

milk (Pers. shir), and similarly employ an egg and melted butter to

represent the gau hudhah, lit. ‘beneficent cow,’ in the ceremony. The

faithful of both communities agree in regartling the true Zoroastrian

sacrifice to be a bloodless sacrifice, an offering of ‘good thoughts, good

words, good deeds,[33]

accompanied by praise and thanksgiving, with appropriate ceremonies. Such

was the sacrifice offered by Zoroaster himself in the Yashts, after the

manner of Ahura Mazda,] although the Avesta does allude to the sacrifice

of animals, once, for example, in the Yasna, and several times in the

Yashts, which represent Vishtaspa and the heroes of old as sacrificing

thousands of animals, some of which must have been slain as a

blood-offering.[34]

|

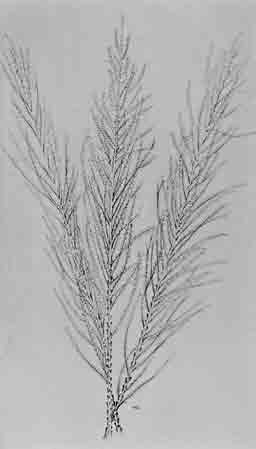

|

Spray of Barsom Plant |

A possible survival of the ancient custom

of animal sacrifice may survive at. Yezd, down to the present, in the

celebration of the Jashn-i Mihrgan, ‘Sacrifice to Mithra,’ although the

views on this subject may differ.[35]

This festival falls on the day of Mihr, in the month of Mihr

(February-March), and is an important one among the Persian Zoroasrians,

as they prolong it for five days, till the day of Bahram, or Verethraghna.

According to the account I received, it commemorates the victory gained by

Feridun (Avestan Thraetaoma) over the Babylonian tyrant Zohak (Avestan

Azhi Dahaka), whose cruel rule oppressed Iran for a thousand years. ‘The

Persian Zoroastrians used to believe, and some of them still believe,’ as

my authority informed me, ‘that at this festival Feridun sacrificed sheep

and bade his subjects to follow his example in this respect, and to eat,

drink, and be merry, because of the overthrow of their arch-enemy. It was

accounted meritorious, therefore, to celebrate the occasion joyfully and

to sacrifice a sheep or a goat in every house, or, if the family were

poor, to kill a chicken. The priests themselves at first used to kill the

animals, but the people afterward did this at home, sprinkling some of the

blood on the door-posts and over the lintel, and cooking the rest of the

blood with suet and onions, as a dish to be eaten with unleavened bread.[36]

Since it was regarded not merely as a sacrifice but as a burnt-offering

unto Mihr-i Iran-davar, Mithra, Judge of Iran,’ the flesh of the sheep and

goats, when roasted, was carried to the fire temple, prayers were said

over it by the priests, to whom a share of the flesh was given, a portion

was set aside for distribution among the poor, and the remainder was taken

home to be eaten by the family and their friends. ’Such is the account I

received from my informant, who added, ‘this custom is now dying out; the

people are becoming wiser and saner, and outgrowing this cruel practice

and bloody rite, which the Parsis of India do not recognize and like which

they have nothing.’

After leaving the fire-temple I asked if

I might visit the Barashnum Gah, a place set apart for the performance of

the ablution for nine nights, as I shall describe in the next chapter.

Since it was situated in another street I had an opportunity, both when

going and returning, to see more of the Parsi quarter of the town and make

further observations as to the community and its general condition. As

there are about eight thousand Gabars in Yezd, they occupy a not

inconsiderable section of the city. I t is known as the Mahallah-i Pusht-i

Khaneh-I Ali, or Mahallah-I Pusht-i Khanahi Ali, the Quarter in the Rear

of Khan Ali, or of Ali’s House,’ and I subsequently learned that they have

a tradition current among them as to the origin of this name. The common

belief is that the designation by Ali’s name is due to a device resorted

to by the worshippers of Mazda in order to escape persecution at the hands

of their Mohammedan enemies after the Arab conquest. They pretended, it is

said, that Ali, the cousin and son-in-law of Mohammed, had a house in this

part of Yezd and that he settled the Zoroastrians here, in order to shield

them from persecution; and that they were Ali’s cowherds. In support of

this claim they cleverly urged the plea that the name Gabran, ‘Infidels,’

by which they were stigmatized, and the modern pronunciation of which

among the Parsis of Yezd would be Gav-ran or Gaur-un, really meant Gau-run,

‘cow-keeper,’ and that as Gabars the Zoroastrians were therefore worthy of

Moslem protection. As I know through Khodabakhsh Bahram Ra’is, the better

educated among them regard this explanation of the name of the quarter as

a mere fiction, a piece of popular etymology, and they suggest a more

probable interpretation. The name Ali, they say, is not an uncommon one

among the Persians, and this was probably the name of a land-owner, or

wealthy Khan (Pers. Khan), who had a caravanserai outside the old part of

Yezd, near where the Parsi quarter now is, and the Zoroastrians settled

there, ‘back of Khan Ali’ (not khanah, ‘house’), so that the designation

has nothing to do with the house of Ali, the successor of Mohammed.

Some details regarding the general

condition of the so-called Gabars in Yezd and its environs may be of

interest. A large proportion of the Zoroastrians who live outside of the

city itself, especially in the neighborhood of the flourishing town of

Taft, are occupied in gardening and the cultivation of the soil. According

to the Avesta, as I have already stated,[37]

agriculture is one of the noblest of all employments, because he who sows

grain, sows righteousness, and one of the most joyous spots on earth is

the place where one of the faithful sows grain and grass and fruit-bearing

trees, or where he waters ground that is too dry and dries ground that is

too wet.[38]

The Zoroastrians who dwell within the

city are largely occupied in trading.[39]

This privilege was not accorded them until about fifty years ago, and they

are even now subject to certain restrictions and exactions to which no

Mohammedan would be liable. They are not allowed, for instance, to sell

food in the bazaars, inasmuch as that would be an abomination in the eyes

of the Moslems, who regard them as unbelievers and therefore unclean.

Until 1882 they were oppressed by the jazia tax, a poll tax imposed upon

them as non-believers, and this gave an opportunity for grinding them down

by extortionate assessments and trading-tolls. The jazia was finally

repealed by Shah Nasr ad-Din, who issued a firman to that effect,

September 27, 1882. It was largely owing to influences brought to bear

upon him by the Parsis of Bombay that the Shah was led to make this

liberal-minded move. They worked through the agency of the Society for the

Amelioration of the Zoroastrians in Persia, which they had founded with an

endowed fund in 1854, sending at the same time a representative to Iran to

look after the interests of their co-religionists.[40]

Up to the time of the Shah's firman, a Zoroastrian was not allowed to

build an upper story on his house, or, in fact, erect a dwelling whose

height exceeded the upstretched arm of a Musulman when standing on the

ground.[41]

Even within a year after the firman was issued, a Zoroastrian in one of

the neighboring villages is said to have had to flee for his life because

he had ventured to go beyond the traditional limits and add an upper room

to his abode, and another Gabar, who was mistaken for him, was killed by

the enraged Musulmans.[42]

|

|

Yezd Types |

|

(Left to Right) Parsi woman; English

woman in Parsi dress; Armenian girl; Parsi woman. |

As regards their dress, moreover, the

Zoroastrians have always been obliged to adopt a style that would

distinguish them from the Mohammedans, and it is only within the last ten

years that they could wear any color except yellow, gray, or brown, and

the wearing of white stockings was long interdicted. The use of spectacles

and eye-glasses, and the privilege of carrying an umbrella, have been

allowed only within the same decade, and even now the Gabars are not

permitted to ride in the streets or to make use of the public baths (hamam);

but the latter prohibition, as they told me, is no longer a hardship,

because they have built a bathing establishment for their own use. A score

of petty annoyances that they have to undergo might be cited in addition

to the more serious disqualifications; but enough have been given to show

the disadvantages under which they labor and the persecutions to which

they are exposed. In 1898 the present Shah, Muzaffar ad-Din, sought to

relieve their condition further by issuing a firman revoking the formal

disabilities from which they suffered. While imperfectly observed, this

decree has contributed, in spirit at least, to bettering their position.

The spread of Babist doctrines, which favor religious liberty and

toleration, has possibly contributed also by lessening intolerance on the

part of the Mohammedans. The presence of Europeans has likewise had a

salutary effect and aided considerably in the general advance. But the

most has been done by the Bombay Society for the Amelioration of the

Zoroastrians in Persia, whose funds have helped the Gabars and whose

reform measures have tended to their general good, so that their numbers

have increased considerably within the last fifty years.[43]

Nevertheless, they still do not feel themselves free from oppression, and

they constantly have to avoid trouble and persecution by yielding to

Moslem prejudice. In fact, their lives are in danger whenever the

fanatical spirit of Islam breaks out, as was the case about a month after

I was in Yezd. A general Musulman rising then took place against the Babis,

a large number of whom belonging to the Behai branch are found at Yezd.

These Babis were massacred by scores, and even hundreds, or were subjected

to shocking outrages and cruel indignities. The Zoroastrians feared that

they would suffer the same fate, and I was informed on the authority of

one who had witnessed the horrors that such might have been the case if

the fanatical wave had not been broken in its course by the prompt and

energetic intervention of the Europeans in telegraphic communication with

the authorities in power at Teheran.

|

|

School Boys at Yezd,

Mostly Zoroastrian |

The organization of the Zoroastrian

community at Yezd has already been indicated in a general way. The

spiritual guidance is in the hands of the priesthood (dasturs, mobeds, and

herbeds), but the authority which they exercise is greatly limited by the

fact that those who do not wish for any reason to accept it can simply

throw it off and act in accordance with the rule of the Moslems around

them.[44]

In civic matters the community is under the leadership of a synod, the

Anjuman (Av. hanjamana, 'assembly, convention'), headed by a kalantar, or

mayor, the present incumbent of that office being Kalantar Dinyar Bahram

whose hospitality I have described, and whose official duties often take

him to Kerman, Anar, and other towns in this region where there are

Zoroastrians.

With the Kalantar's young son Bahram I

formed a friendship in the short time of my stay, for he acted as my guide

round the city and through the mazes of the bazaar. He was a bright,

intelligent fellow, straightforward and honest, manly in his bearing, and

agreeable in his manners. I could picture from him what might have been

the type of youth in Zoroaster's day, since the blood of the ancient faith

flowed in his veins by direct descent. I liked his naturalness and lack of

affectation, and certain of his characteristics were charmingly na'ive,

for when I took his photograph he instinctively plucked a rose to hold in

his hand (for a true Persian portrait would be artistically incomplete

without a rose), and in the other hand he held up to view his European

watch. I could understand his pride in this respect, since a Zoroastrian

would not have been allowed some years ago to carry a watch or even to

wear a ring.

|

|

A Zoroastrian convert to Islam |

Benevolence is a Zoroastrian

characteristic, and the Avesta inculcates the virtue of generosity. Many

of the Parsis of Yezd live up to this doctrine so far as their limited

means will allow. As an instance of this I may cite the following example.

When the English Christian Mission at Yezd was in need of quarters for its

hospital -- a branch of their work with which the Parsis especially

sympathized -- a prosperous Gabar merchant, named Gudarz Mihrban, came

forward and donated to the cause a large caravanserai and its property,

including a house that adjoined it. The structure of this erstwhile

halting-place for caravans lent itself in a remarkable manner to the uses

to which it was now to be put: the central court that once was filled with

camels, asses, and pack-mules was turned into a pretty garden ; and the

old-time lodgings of the camel-drivers and muleteers were transformed into

chambers and wards for the Good Samaritan work.

[1]

These are the figures given me at Teheran by Mr. Ardeshir Reporter, Agent

of the Society for the Amelioration of the Zoroastrians in Persia. See

also p. 336, n. 3, above; p. 376, n. 1, and p. 425,below.

[2]

See my article in Archiv fur Religionswissenschaft,, 1. 364. I have

also been told that the Talmud somewhere speaks of this as the Parsi

manner of sitting at meals, in contrast to the Jewish fashion.

[3]

A number of these manuscripts which are now in Bombay had already been

used by Professor Geldner in the preparation of his edition of the

Avesta. I communicated afterward to the Parsi Panchayat in Bombay the

facts about the manuscripts I had seen at Yezd and also in Mr. John

Tyler’s possession at Tehran,as the Secretary of the Panchayat had

requested from me a report regarding any copies of Avestan texts I

could find.

[4]

See Westergaard,

Zendavesta, preface, P. 21, n. 4, and P. 11, n. 3, Copenhagen,

1852-1854 ; see likewise his letter to Dr. Wilson, quoted by Karaka,

History of the Parsis,1. 60.

[5]

This work corresponds to the Pahlavi

treatise Pandnamak-i Vazhorg-Mitro-i Bukhtarkan which has

survived. See on this point West, Grundr. iran. Philol.2.113.

[6]

See Danlatahah,

Tadhkirat ash-Shu'ara,

ed. Browne, p. 30, London, 1901, and

compare Browne, Literary History of

Persia, pp. 12, 346-387.

[7]

See p. 430, below,

and compare my Zoroaster, pp.

17, 85, 192, 202

[8]

See pp. 87, 103,

above

[9]

See Vd. 19. 3, 11. The

view that the text contains an allusion to a mountain called 'Paitizbara '

(paiti zbarahi) from which the Darejya flows, is found in an essay in

English by Ervad Sberiarji Bharucha, Zoroastrian Religion and Customs, p.

3, Bombay, 1893, and this treatise has been translated into Persian by

Master Khodabakhsh. The same interpretation appeared to be found in a

lithographed work from which they quoted, and which was a compilation by

Mirza Tath-ali-Khan Zanganahi (so far as I could catch the name). The

comparison of the Daraj with Karaj is due to this latter

writer. There are some incidental references to the Karaj in Yakut,

pp. 65, 478, 488 ; see also p. 443, below.

[10]

I have reproduced the photograph in

Chap. 28, below. For paiti zbarahi, see Bartholomq Air. Wb. p. 1699.

[11]

See my Zoroaster, pp. 194-195.

[12]

For the main sources, see my

Zoroaster, pp. 280-286.

[13]

According to the Parsi Prakash, ed.

Bamanji Bahramji Patel, p. 10, Bombay, 1888, the above-mentioned

Dastur Azar Keivan bin Azar Goshasp was a learned and well known

Persian priest who believed in a universal religion. After spending

twenty eight years of his life in meditation he came to India and

settled at Patna, where he became known as a teacher of a universal

creed. He wrote the Makashifat-i Azar Keivan and died at Patna in

1614, at the age of eighty five. For this information from the Parsi

Prakash I am indebted to my pupil and friend, Errad Maneckji

Nusservanji Dhalla, of Karachi, India, a student at Columbia

University. For a note on Farzanah Bahram ibn Farbad, see Shehriarji

Bharncha, The Dascitir, in Zartoshti, 3. 122, Bombay, 1908.

[14]

In the Dasatir (see Shehriaji

Bharnclra, op. cit. p. 121) Zartoshtis the thirteenth in the line of

prophets. Such is the view held also by some of the theosophists among

the Modern Parsis of India, certain of whom regard him as the seventh

of the name. See Bilimoria, Zoroastrianism in the Light of Theosophy,

p. 4, note, Bombay, 1896.

[15]

On the whole subject

of dualism, see the views expressed in my article in Geldner. iran. Philol.

2.626-631, 617-649, 663.

[16]

Many of the phonetic features are

common in the ordinary pronunciation of the Indian Parsis, except

among the trained scholars.

[17]

For the sake of parallelism I have

here retained, with trifling modifications, the older transliteration

of Justi.

[18]

The a is sometimes labialized to aw

(Eng. law).

[19]

It is only the younger generation of

Zoroastrian students at Yezd that has come into close contact with the

Zoroastrians of India, through the influence of Master Khodabakbsh and

a few other scholars who have been in Bombay.

[20]

The name Dar-i Mehhr, 'Shrine of Mihr

' (used also in India) contains a reminiscence of the ancient Mithraic

worship, but is now used (like Adarian, ‘pyraea') merely as a

designation for a small chapel or shrine of fire.

[21]

See pp. 131-143, above.

[22]

Cf. Vd. 3. 1.

[23]

Cf. Vd. 14. 2; 18.27, 71.

[24]

The intonation of both the priests

was loud and resonant and more swift than that

of the Pami dasturs I had heard in Bombay and Udvada, and I observed

the Same peculiarities in pronunciation that I had observed in the

conference of the forenoon.

[25]

See my Zoroaster, pp. 288-289.

[26]

See pp. 216-218, above.

[27]

I refer to the

sc-called urvis-gah connected with the fire-temples at Udvada, Navsari,

and Bombay. For a photograph and a description of the latter, together

with a representation of the various implements and utensils employed

in the sacrifice, see Darmesteter, Le ZA. 1. introd. p. 72 (pl. 4),

and compare the interesting notes descriptive of some Parsi

ceremonies, by Haug, Essays on the Parsis, 3d ed., pp. 302-400; cf.

likewise my note in JAOS. 22. 321.

[28]

See Ys. 10.3, and Rig Veda 5.86. 2;

10. 34.1.

[29]

The Zoroastrians of Yezd, like the

Indian Parsis, agree in regarding the pmegranate as the representative

of the Avestan urvaru hadhanaepata; on the latter, compare Haug,

Essays on the Parsis, pp. 251, 399, and West, SBE. 37. 186.

[30]

The Avestan words employed in

connection with the barasman indicate that the twigs were originally

spread (star-, frastereta-), then gathered into a bundle and hound (yuh-,

aiwyasta-, aiwyhana-); see the references under each of these words in

Bartholomae, Atr. Ipb. pp. 98,947,1290, 1595.

[31]

Ezekiel 8. 16, 17.

[32]

My friend Mr. Percy Bodenstab, of

Yonkers, has made a drawing of the sprays (here reproduced) in a

reduced size; to convey a clearer idea it would be necessary to

reclothe the branches with the softest green color imaginable.

[33]

See Yt. 6. 17,

104; 9. 28 ; 17. 44 (rendering gava each time as ‘milk’).

[34]

See Ys. 11. 4 ; Yt. 6.21, 25, 33,

108; Yt. 9. 25; compare also the description of the Magian sacrifice

given by Herodotus, History, 1. 132. Observe likewise that on the eve

of battle (Yt. 6.68) Jamaspa himaelf offers an animal sacrifice.

[35]

The notes which I present on the

Jashn-i Mihrgan are given on the authority of Khodahakhsb Bahram Ra’is,

who, it should be noticed, attributes the origin of the custom to

Mohammedan influence after the Arab conquest, like the sacrifices at

the feast id-i Kur-ban, referred to above, p. 162, n. 1. The opinion

of the Parsis in India would also be in favor of his view. See Modi,

Meher and Jashne Meherangan (Mithra and the Feast of Mithras), Bombay,

1889; of also Marquart, Untersuchungen zur Ceschichte von Eran, 2.

132-136, Leipzig, 1905.

[36]

It is interesting

to note the resemblance between this old-time Persian custom and the

observances of the Jewish Passover.

[37]

See p. 246, above.

[38]

See Vd. 9. 31 and

Vd. 3. 4.

[39]

The Zoroastrians in general appear to

have an especial aptitude for business, and they appear rather to

amept than reject the designation 'Jews of the East' that is sometimes

applied to them because of their commercial activity.

[40]

For an account of

the efforts for the abolition of this tax, see Dosabhai Framji Karaka,

History of the Parsis, 1. 7282, London, 1884; cf. also p. 397, below.

[41]

The comparative

scarcity of upper stones on the houses in the Gabar quarter is

still noticeable.

[42]

For this point and the next, see

Malcolm, Five Years i n a Persian Town, pp. 46, 49, London and New

York, 1905. This interesting book on life at Yezd appeared after the

present chapter was written, but I have been able to incorporate one

or two references, and I would recommend to the reader’s attention Mr.

Malcolm’s remarks on the restrictions in general upon the Gabars (pp.

44-63).

[43]

In 1854 the number of Zoroastrians in

the vicinity of Yezd was given at 6658 souls (Karaka, History of the

Parsis, 1. 55 ): in 1882 as about 6483 (Houtum-Schindler, Die Parsen

in Persien, in ZDMG. 26. 54); in 1903 as between 8OOO and8500,

including the environs of Yezd (these last figures being given to me

in Teheran by Mr. Ardeshir Reporter, Secretary of the Society for the

Amelioration of the Zoroastrians).

[44]

For the relations between the

spiritual and temporal powers in ancient times, see Wilhelm, Kingship

and Priesthood in Ancient Eran. pp.1-21, Bombay, 1892 (translated from

his German treatise in ZDNG. 40. 102-110).

|