|

Series:

Library

Editor:

Jamshid Varza

Author:

Abraham Valentine Williams Jackson

Subtopics:

Reference:

Related

Articles:

Related

Links:

|

From Constantinople to the home of Omar Khayyam; Chapter IV

Abraham Valentine Williams Jackson

The McMillan Company, 1911

'By a

towne called Backo, neere

vnto which towne is a strange thing to behold

for there issueth out of the ground a marueilous

quantitie of Oyle.'

- JEFFBEY DUCKET, Fift Voyage into Persia, p. 439.

|

|

An oil spouter blowing off |

A VISIT

to the oil wells at the fields in the

Balakhany-Sabunchy-Romany region, about eight miles northward from

Baku, or at Bibi Eibat, some three miles south

of the city, is an interesting experience. It was my pleasant privilege, during

my first visit at Baku, to pay

such a visit under the guidance of the. British vice-consul,

Mr. Urquhart, whose kindness was equaled only by his

knowledge of Baku

and all that relates to the city.

|

|

The oil fields ablaze |

On entering the fields, one becomes lost amid a maze of towering

derricks, erected over the wells to operate them. These pyramidal wooden

structures are covered with gypsolite or iron plating as a protection

against fire. The shafts of the wells are often sunk fifteen hundred or two

thousand feet to strike the oil.

Metal tubes, from six to twelve inches in diameter, are inserted in the bores so

as

to serve as pipes through which the precious liquid may spring

upward or be drawn to the surface by a metallic bucket, the ' bailer,’ ready to

pass in iron conduits to the refinery in Black Town and become one of the

richest articles of commerce.

|

|

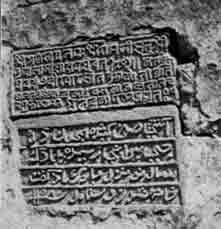

Inscription of the shrine of the fire

temple, Baku |

There are over two thousand of these wells in the

Apsheron (Absharan) Peninsula, on which Baku stands, and one can

hardly conceive of the activity implied in this wilderness of truncated pyramids, each in itself a

source of revenue that is a fortune.

The stupendous figures of the annual yield from these fields is almost

staggering. It runs up into the many millions of 'poods,'

a pood being approximately five American‘ gallons.

Sometimes the borings strike ‘fountains,’ and then a tremendous 'spouter’ is the result, belching up its concealed contents

with the force of a geyser, and perhaps bringing ruin instead o f fortune to its

owner unless the giant can be speedily throttled and gagged. Thrilling

descriptions are given of how some of these monsters have, within the last

generation, thus wrought destruction to everything within immediate reach.

The magnificence of the spectacle is surpassed only by the awful grandeur when

fire adds terror to the scene. On all

occasions when visiting the petroleum fields it is advisable to wear old

clothes, for one may find it anything but the oil of gladness, as I learned from

sad experience when one of the spouters blew off

unexpectedly while we were near it, filling the air with a deluging rain from

whose greasy downpour there was no escape.

|

| The fire temple and its

precinct at Surakhany, Baku |

All who have been at

Baku, and almost all who have heard of Baku, know of the Fire Temple at Surakhany in the

northern environs of the city. The place is easily reached by driving,

or better by rail with a short spin in a

phaeton afterwards. Common tradition has long associated the

one-time sanctity of this region with the veneration of the so-called

Zoroastrian Fire-worshipers, though whether with absolute justice must remain to

be seen.

Zoroaster flourished at least as early as 600

B.C.,

and his religion became the faith of Ancient Iran, continuing as its

creed until the seventh century of the Christian era. This remarkably pure

religion, which bears striking resemblances to Judaism and to our own faith,

which it antedates,

was supplanted

in the seventh century of our era by the new and militant creed of Islam. Ormazd yielded his throne in heaven to Allah, the Avesta

gave

place to the Kuran, and Zoroaster was superseded by

Muhammad as the acknowledged prophet of truth. Having previously devoted a

volume to the life and legend of Zoroaster and a monograph to his religion, as

well as given special attention to the subject as a whole in my former book on Persia,

I shall not now go further into the history and fortunes of the ancient creed.

Suffice it to say that a few Zoroastrians refused to

adopt Muhammadanism when the conquest came (650 A.D.). Some of this scanty band sought

refuge and freedom to worship Ormazd in India, where

they became the ancestors of the flourishing community of the Parsis in Bombay; a remnant persisted in staying in their

old home, only to meet with persecution and hatred as infidel Gabrs,

'Ghebers, Unbelievers,’ and these still find an insecure

asylum at Yazd and Kerman in the desert, while a handful even reside in Teheran.

They see not God but the purest effulgence of God in the Flame Divine, and they

abhor the name of 'Fire-worshipers.’ Yet in the eyes of Mohammedans they are

such, and it is not strange that local tradition associates their name with

Baku

as the very source of eternal fire.

|

|

Inscriptions XII and XIII on the walls of

the precinct |

I have said that ' tradition ' has

connected the name of the

Zoroastrians with the igneous realm of Baku, but I

have not been able to trace it back more than two hundred years, as I shall show

below, and I believe that some of the sweeping statements made on the subject by

modern writers (including myself) may have to be modified so far as

Zoroastrianism is concerned. The present shrine is apparently of Northern Indian

rather than of Persian foundation, although possibly the site itself may have

been a hallowed one in ancient times; but before I turn to that matter, I shall

give a description of the sanctuary and its surroundings.

The sacred precinct consists of a

walled enclosure that forms nearly a parallelogram, following the points of the

compass. Its length is about thirty-four yards from north to south, or forty on

its longer side; the breadth is about twenty-eight yards from east to west. The

central shrine stands nearly in the middle of the court. A square-towered

building, approached by a high flight of steps, rises toward the northeast

corner. The walls of the precinct are very thick, as they consist of separate

cells or cloistered chambers, running all the way around, and entered by arched

doors. The whole is solidly built and covered with plaster.

|

|

The central sanctuary, eastern elevation,

with inscription. |

The structure in the middle is a square

fabric of brick, stone, and mortar, about twenty-five feet in height, twenty

feet in length, and the same in width, with arched entrances on each side facing

the points of the compass.

These entrances are approached by three steps each on the north and east sides,

and by two steps on the south and west sides, where the ground is slightly

higher. In the middle of the floor is a square well or hole (visible in my

smaller photograph), measuring exactly forty and one-half inches (1 m. 13 cm.)

in each direction. Evidences are seen of pipes once used to conduct the naphtha

to this and to the roof. The top of the shrine is surmounted

by four

chimneys at the corners, from which the flaming gases used to rise when the

temple was illumined in times gone by. In the middle of the roof is a square

cupola, from whose eastern side there projects, like a flag, a three-pronged

fork that resembles the trisula,

or trident, of the Indian god Siva.

High over the

archway

on the eastward front is a double oblong tablet, three and a half

feet high by two broad, the upper section of which shows a swastika emblem and a

sun, four flowers, and several nondescript figures.

The lower section is devoted to an inscription in nine lines in the Nagari character of India, beginning

Sati Sri Ganesaya namah,

'In verity, Homage to the Honored Ganesa

‘the common invocation, in Sanskrit writings, to the divinity who removes

obstacles. The inscription continues, apparently in the

Marwar dialect of the Panjab,

stating that the shrine was built for Jvalaji (the

same as the flame-faced goddess Jvala-mukhi, of Kangra in the Panjab),

and quoting a Sanskrit couplet on the merits of a pilgrimage and pious works. It

concludes with the date of the Vikramaditya era, 'Samvat 1873‘ (=1816

A.D.).

As the

inscription is high and in a position not easy for photographing, it was

necessary to perform the somewhat acrobatic feat of perching on the top of a

long ladder that was shakily held in

the air, about ten feet off, by six men. Considering the

difficulties of the task, the photograph (the only legible one I have seen)

turned out to be quite a success.

|

|

The portal and tower edifice in the

eastern wall, fire temple of Baku |

Around the walls of the precinct, either above or near the side

of the doorways of the cells, are fifteen more dedicatory tablets sunk in the

plaster and written, with one exception, in the same Nagari

character, prevailingly used for Sanskrit, or in a variety of this Indian

alphabet. In my notebook I gave them numbers, beginning at the northwest corner

near the usual entrance. Two of them in the northern wall are in the

Panjabi language and script of Upper India and are of

Sikh origin, as they quote from the Adi Granth, the

sacred book of Nanak’s religion, which was founded about 1500 A.D.

Their date, however, must be two centuries or more after that

era, as was shown by Dr. Justin E. Abbott, of Bombay, from a couple of

photographs of two other tablets in the southern wall, which I brought back

after my first visit to the temple.

One of these latter inscriptions (XII = also published previously by Colonel C.

E. Stewart in JRAS. 1897, pp. 311-318)

is in Nagari and bears the date 'Samvat 1802' = 1745 A.D.; the other

(XIII), immediately below it, is in Persian, the only one in that language, and

gives the same year according to Mohammedan reckoning, Hijra

'1158' = 1745 A.D.

I have since

found similar dates on still others of the tablets within the precinct. For

example, one of the tablets (I) near the west-by-north corner, beginning Sri Rama sat, contains the

year 'Samvat 1770' = 1713 A.D.,

and seems to be the earliest date found. One of the northern tablets (IV)

appears to have the date 'Samvat 1782' (?) = 1725 A.D.,

although the figures for 8 and 2 are very uncertain. Another (XI), on the east

side, bearing a swastika followed by Om Sri Ganesaya namah, has at the end (though almost illegible)' Sam(v)at 1820' =

1763, Yet another (IX), also on the eastern wall, concludes, 'Samvat 1839' = 1782 A.D. (the last

cipher being slightly broken); while still another (V), on the northern side,

closes, as I read it, with '1840' = 1783

A.D.

They all belong, therefore, to the eighteenth century.

|

|

Worshipers in the Baku temple in 1805 |

Besides the total of fifteen inscriptions, dated or undated,

within the circumvallation, there are two more on the outside, connected with

the square tower near the northeast corner. The lower one of these (XVI) is

inscribed on a black stone over the arch, facing east ; it begins with the

common Ganesh formula, mentions

Jvala-Ji, the divinity of fire, and concludes with the date 'Samvat

1866’ = 1809 A.D.

The upper one (XVII), placed on the outside of the story above, is likewise in Nagari, but is less clearly written, and the close is hardly

legible in my photograph, which was taken with difficulty, as I had to be held

up over the top of the high doorway while I made the snapshot. The tablet has

been stupidly set in, or reset, upside down, and below it is scrawled in Russian

block letters the name 'N. Mintova.’

As I secured photographs of all the inscriptions, and the

majority were successful, in case the tablet photographed was still legible,

it will be possible to study them in greater detail later, and I hope to publish

them elsewhere in cooperation with Dr. Abbott, whose interest in the subject has

already been proved.

After this long, and, I fear, somewhat technical, disquisition, I

turn to the more attractive problem of determining the possible age of the

temple and its buildings. I may state at once that I used to hold the generally

current opinion that the sanctuary was of Gabr, or Parsi, origin -a

Zoroastrian fire-temple.

Further study of the subject has forced me to abandon this view (certainly for

the present temple) as the following paragraphs will show.

So far as my researches go, I have not been able to find any

allusion to a temple on the site in the classic writers of Greece and Rome;

nor

in the early Armenian authors;3

nor do the medieval Arab-Persian geographers refer to it,

as we might

expect, when mentioning the naphtha wells ; nor again is it spoken of by the

European travelers Barbaro, Jenkinson, or Ducket in the sixteenth century, nor by

Olearius in the seventeenth century, nor by John Bell early in the

eighteenth, when touching on Baku, nor yet, earliest of all, by Marco Polo --

all of whom have been cited above. The oldest reference I have been able thus

far to discover (though I stand ready for correction) is by Jonas

Hanway in the year 1747, who was practically contemporaneous with the

inscriptions given above. Hanway himself did not visit

the temple when he was in Baku,

but he gives a detailed and accurate account of it, based upon 'the current

testimony of many who did see it.’ He speaks of the worshipers as ‘Indians,

'Gaurs,' or 'Gebrs,’ and devotes a chapter to describing the religion of

Zoroaster, somewhat in detail.1

The heading of this chapter reads: --

‘A succinct account of the antient

PERSIAN

religion, with several minute particulars relating to the everlasting fire near

BAKU,

and the extraordinary effects of this phsnomenon, to

which the INDIANS

pay divine honours.’

|

|

Scene at fire temple of Baku, 1825 |

After giving some idea of Zoroaster and his

doctrines as followed by the early Persians, he

adds:

-

'These opinions, with a few alterations, are still maintained by some of the

posterity of the antient INDIANS and PERSIANS, who are called GEBERS, or GAURS,

and are very zealous in preserving the religion of their ancestors; particularly

in regard to their veneration for the element of fire. What they

commonly call the EVERLASTING FIRE, near

BAKU, before which

these people offer their supplications, is a phaenomenon

of a very extraordinary nature, in some measure peculiar to this country, and

therefore deserves description. This object of devotion to the GEBERS,

lies about 10 ENGLISH miles north-east by east from the city

of BAKU,

on dry rocky land. There are several antient

temples built with stone, supposed to have been all dedicated to fire; most of

them are arched vaults, not above 10 to 15 feet high. Amongst others there

is a little temple, in which the INDIANS now worship:

near the altar, about 3 feet high, is a large hollow cane, from the end of which

issues a blue flame, in colour and gentleness not

unlike a lamp that burns with spirits, but seemingly more pure. These INDIANS

affirm,

that this flame has continued ever since the flood, and they believe

it will last to the end of the world; that if it was resisted or suppressed in

that

place, it would rise in some other. Here are generally forty or fifty of these poor devotees,

who come on a pilgrimage from their own country, and subsist upon wild sallary, and a kind of JERUSALEM artichokes, which are very good

food, with other herbs and roots, found a little to the northward. Their

business

is to make expiation, not for their own sins only, but for those of

others, and they continue the longer time, in

proportion to the number of persons for whom they have engaged to pray. They

mark their foreheads with saffron, and have a great veneration for a red cow.

They wear very little cloathing, and those who are of

the most distinguished piety, put one of their arms upon their head, or some

other part of the

body, in a fixed position, and keep it unalterably in

that attitude. A little way from the temple is a low clift

of a rock, in which there is a horizontal gap, 2 feet

from the ground, near 6 long and about 3 feet broad, out of which issues a

constant flame, of the colour and nature I have [p.

382] already described : when the wind blows, it rises sometimes 8 feet high,

but much lower in still weather : they do not perceive that the flame makes any

impression on the rock. This also the INDIANS worship, and say it cannot be resisted but it will rise in some other

place. About 20 yards on the back of this clift is a

well cut in

a

rock 12 or 14 fathom deep, with

exceeding good water.’

The descriptive portion of this account, as already stated, is

correct, being based upon information received from accurate observers. It is

plain from the description itself that, if actual Gabrs

(i.e.

Zoroastrians, or Parsis) were among the number of the worshipers at the

shrine, they must have kept in the background, crowded out by Hindus, because

the typical features which Hanway mentions are

distinctly Indian, not Zoroastrian. The allusion

to the tilak mark on the forehead, the veneration

paid to the red cow, the diet of herbs and fruits, the scantiness of clothing, and the Yogi posture of the urdhva-bahu ascetics, with

withered arms, are all Brahmanical.

Further external evidence of the same character

may be gained

from the testimony of succeeding travelers. Thus, S. G. Gmelin (1771) describes the various

Yogi practices of the devotees, especially of one ascetic who had held his arm

up for seven years, until it became stiffened -a

species of self-castigation that is only Hindu and was never

sanctioned by Zoroastrianism. Similarly, Jacob Reineggs, who made several

journeys in the Caucasus before 1796, in describing the 'Ateschjah,’ speaks of the devotees as 'Indianer,’

who were formerly called 'Geber '; and he mentions

their Yogi austerities, noting also that they burned their dead -- a fact

sufficient in itself to prove they could not have been true

Zoroastrians.

Pointing in a like direction is an incidental reference by

Morier (between 1800 and 1816), when he casually mentions meeting a '

Hindu pilgrim ' returning from Baku to

Benares.

The scholar

Eichwald (1825-1826), who gives a clear description of

the temple and some of the ceremonies, mentions the names of Hindu divinities as

invoked in the worship – Rama ('Rahma'), Krishna ('Krisehni'), Hunuman ('Hanuma'), and Agni (' Aghan '), the god of fire

-- all of which are Brahmanical, as is likewise the

blowing on the conch shell ('Tritonmuschel') in the

ritual. His picture of the temple, with its naked worshipers (here reproduced),

his reference to the Kangra temple in India, and above

all, his mention of a place in the cloister where the devotees burn the body of

any of their number that may die, leave no doubt as to the Hindu character of

the shrine at that day. He himself (pp. 216-217) properly emphasizes the fact

that the Indian fire-worshipers at the temple had wrongly been called Gabrs ('Gueber').

The German poet and student Friedrich

Bodenstedt, writing in 1847, after spending seven years in Russia and the

Caucasus, in telling of the 'Ateschgah,’ speaks of the

Hindu god Vishnu ('Wischnu’) and of the ritual summons with the 'Tritonmuschel,’ and looks upon the idolatrous worship and

barbarous self-mortification of the body as if it were a decadence

from the exalted religion of Zoroaster (‘die

erhabene Lehre Zerduscht’s'), whereas it

was really only Indian.

In November, 1858, the noted French writer

Alexandre Dumas visited the temple. Throughout his description he

assumes

that the sanctuary was a fane of the Zoroastrian fire-worshipers ;

and he refers to its ministrants as ' Parsis,’ 'Guebres,’

and 'Madjous,’ or descendants of the Magi. But it is

clear from his description of the ritual, which he himself calls 'une messe

hindoue,’ together with his allusion to the frequent recurrence of the

divine name ‘Brahma' in the chant, the employment of cymbals, and the use of

prostrations in the service, that the worship was simply Hindu.

Petzholdt

(1863-1864) gives an almost equally detailed description of the sanctuary and

the ' Hocus-pocus’ ceremonies that were performed, but has nothing to show that

there was anything Zoroastrian in their nature.

About the same time as Petzholdt, the

Englishman Ussher visited the temple, on

Sept. 19, 1863 (or 1864 ?), calling it 'Atesh

Dja,’ the Arabic pronunciation ’ of the Parsi name Atash Gah.4

His diary notes were not originally prepared for publication, and he disclaims

for his volume any pretence to special scientific acumen; but while he supposes

that the pilgrims to the temple were ‘devotees from among the fire worshipers of

Persia and India' (p. 207), and even though he mentions Zoroaster and the god

Ormazd, his testimony, like that of his predecessors, to the effect that

the steps of the little altar in the priest’s cell were ‘covered with brass and bronze images' (p.

208), bears on the face of it the evidence that the ministrant was a Hindu. His

own words, in fact, state this when he appends : 'The present inhabitants were

only two in number, both from India, one being

a native of Calcutta, the other

of Delhi…

They wore the usual Indian dress and turban, having in addition a streak of

yellow paint on the forehead between the eyes.’These

priests are – pictured in the colored frontispiece to his book as engaged in

performing their ritual on the pedestal of stone and mortar which is near the

central shrine, and which, like it, is represented as lighted up with natural

gas; their type is thoroughly Indian, and the ceremonies which are described are Brahmanical, not Zoroastrian.

Ten years later than Ussher, the German

Baron Thielmann visited the fire-temple in October, 1872.

He calls it by the same name, 'Ateschgah,’ and says

(p. IO): ' The priest is sent here for a limited time by the Parsee community of

Bombay;

after a lapse of some years he is replaced. Now and then a pilgrim from the end

of Persia (Yazd,

Kerman) or from India

makes his appearance and remains for several months or years at the sacred

place.’ Proceeding on this assumption, the baron supposed that the worship was

that offered to Ahura Mazda, or

Ormazd; but it is manifest that the ritual which he witnessed and briefly

described, specially the finale of ' a votive offering of sugar-candy made to an

idol on the altar,’ was wholly Hindu, never Parsi.

Thielmann’s further testimony (gathered through an interpreter), to the

effect that ' the priest, according to his own statement, was ignorant of

Zend and also of Sanscrit ' (p. 311), would

militate against the celebrant’s having been a Zoroastrian

dastur, who would surely have known the Avesta. As regards the statement

that ' he understood Hindoostani, Hindi, and

presumably also Parsee,' we may readily believe the first part, though the

assumption as to the

Parsi dialect is far less probable; and we may well

agree with Stewart (p. 314, cited below) that Thielmann

was mistaken.

Still more strong in favor of the Hindu, not Zoroastrian,

character of the present sanctuary is the internal evidence of the inscriptions

which have been mentioned already. The first to draw my attention to this fact

was the Parsi priest Shams Ul-Ulama Jivanji Jamshedji Modi, of Bombay. In a

letter written to me in 1904, after my first visit, and from which I quoted

later in print (JAOS. 25. 304), he expressed his doubts, from the Zoroastrian

standpoint. These doubts (which had been anticipated long before by Eichwald -- see above, p. SO) were further strengthened by

Dr. Abbott’s reading of three of the inscriptions, as already

mentioned ; and they are now wholly substantiated by the other inscriptions,

here made accessible. They are all Indian, with the single exception of one

written in Persian (see my reproduction), which is dated in the same year as the

Hindu tablet over it, as explained above. The Iranian tablet is a quatrain in

not very good Persian, the mistakes of which might have been made by a Hindu

imperfectly acquainted with the language, although Persian is current in

northern India.

Not only this evidence, but also the theory of the Indian origin

of the shrine at Baku, was

anticipated over a decade ago by Colonel Stewart in an interesting article

entitled an 'Account of the Hindu

Fire

Temple at

Baku,’ which was

published, with a reproduction of three of the tablets, in 1897. Stewart had

visited the place in 1866 and again in 1881, and he adds convincing evidence to

show that the sanctuary is Northern Indian in source. He speaks of 'Hindu

visitors who came here after visiting the Temple of

Jawala Mukhi in the Kangra District of the Punjab. The

Kangra

Temple of the

Flame-faced Goddess is well known in India.’

He further states (pp. 311-312) that, when he saw it 'in 1866, one Hindu priest

alone watched the fire, although previously three Hindu priests had always

watched.’ One of these had been murdered by the Muhammadans

for his pittance of money; the other had fled. The third, who remained, spoke Panjabi, the language of at least two of the inscriptions,

and had piously served at Surakhany for many years as

priest of 'this greater Jawala Ji,’

as he called the divinity of flame, a name that appears several times in the

inscriptions mentioned above, and that of course is connected with the Indian

temple at Kangra. Colonel Stewart adds that when he

returned to Baku in 1881 and

again visited the temple, he found the fire extinguished and no priest in

attendance. He furthermore states (p. 314) that near the Afghan border he met

two Hindu Fakirs who announced themselves as 'on a pilgrimage to this Baku Jawala Ji’; and that in 1882, when

he was returning to England, some of the Hindu traders begged to be allowed to

accompany him as far as Baku for the purpose of visiting the shrine. He

supplements this by saying, 'although the Hindus I have met in Persia know about

this temple, I never heard any Zoroastrian in Persia, although I met many,

express any wish to visit it or have any knowledge of its existence.’ His

conclusion on this point is (p. 313), ' there can be no doubt this temple is

not, or never can have been a Zoroastrian temple.’ The structure in the middle

of the sacred enclosure he regards (p. 312, cf. p. 315) as 'a much more

modern building,’ and he considers it to have been‘dedicated to the God Siva,

as

shown by Siva’s iron trident, which was fastened on the roof.’

It was, however, dedicated to some form of the Hindu divinity of fire, as we

have seen.

Additional weight from the Hindu side is given by the style of

architecture of the building. Judged from this standpoint also, irrespective of

anything else, the structure appears to be Indian rather than Persian. Heinrich

Brugsch, who spent part of a day at the sanctuary, about 1884, but says

little about it, noticed that the edifice was built in Indian style (' in seinem indischen Baustyl'),

and it gives an impression similar to that of a Hindu

Dharmasala, or religious

building founded as an act of piety or charity. Stewart accordingly speaks

several times of the whole sanctuary as a 'Dharamsala

' (p. 313), and remarks that it did not resemble the remains of any real

Zoroastrian temple he had seen in Persia. I think we

may readily share his opinion, even if the architecture of the Persian

chapar-khaneh, or caravansarai, may possibly have exercised some slight

influence on the style of the enclosure, and even though one might be inclined

to see remote affinities with the ruined shrine near

Isfahan

and that near Abarkuh.

From all this I believe that, even against our will, we must

reach the conclusion that, whatever the site may possibly have been originally,

the Baku fire-temple, as we now have it, is a Hindu product, and that it is,

more particularly, of Northern Indian origin, where fire-worship was cultivated

from the ancient time of the Vedas. In age the sanctuary can hardly be more than

two centuries old, if we may judge from the half dozen inscriptions that are

dated, as they belong mostly to the eighteenth century.

We may account for its presence at Baku more easily from the fact that '

formerly many merchants lived here, especially Indians,’ as is stated by Hanway (or rather by Cooke’s diary) in 174’7 ; and Eichwald (1825- 826) states that in his time the special

patron of the temple was a rich Hindu, named 'Otumdshen’

(perhaps Skt. Atmajanma),

who farmed the Caspian fisheries and lived mostly at Astrakhan.

I have already (p. 31) mentioned the fact that caravans from

India

were common in the region from early times.

Thus, to our regret, vanishes the legend of the 'Zoroastrian' Atashgah at Baku,

at least in the form in which we have it. The sacred flame that was its source

has likewise vanished, for in 1879 the temple passed over into Russian hands by

a concession of the government, when the last priest sold out his interests to

the Baku Oil Company near the old Kokorev refinery,

and the fire was extinguished forever.

It is true that

photographers may still have the fane illuminated on occasions so as to give a more characteristic picture, or may

paint into their plates the blazing naphtha for more realistic effect; but even

in 1381, when Stewart last visited the shrine, it was under lock and key as now,

and the engineer in charge of the Russian refinery ' relit ' the fire, only to

extinguish it when he left the building, because, as he said, 'he wanted all the

natural petroleum gas for heating the furnaces of his works ' (p. 312). Sic transit gloria ignis! -the flame has perished, a victim to the

commercial value of the precious substance that gave it birth.

And one thing more. By a strange

chance, the bell which once hung aloft from a hook that is still visible in the

roof, and which was rung to mark the progress of the pagan ritual, now swings in

the belfry of a Russian church which was in need of a signal to summon its

worshipers to Sunday service.

Through the kindness of Mr. Wilson D.

Youmans, of Yonkers,

N. Y., I have been most courteously furnished, by the statistician of the

Standard Oil Company of New York,

with the following figures regarding

Baku

: 'During the year 1908 the production of the Baku Field was 465,343,000 poods, equaling 55,863,504 barrels of 42 gallons. The

world’s production of crude oil during the year 1908 was 284614,022 barrels of

42 gallons, and the Baku

production represented 19.6% of the total production of the world. 'The

production of the Baku Field annually since 1903 was as follows : -

|

1903 .

. . 696,581,155 poods

|

1906 . . . . 447,520,000 poods

|

|

1904 . . . . 614,115,445 poods

|

1907 . . . . 476,002,000 poods

|

|

1905 . . . . 414,762,000 poods

|

1908 . . . . 466,343,000 poods

|

See Cust in the article by Stewart, JRAS. 1879, p. 316,

and compare

Henry,

Baku, 26. p. |