|

|

|

|

Dinshah Irani |

One afternoon, in February

1932, when I was sitting in the Board Room of the Trustees of the N. M.

Wadia Charities, in Bombay, two esteemed visitors were announced Dinshah

Irani and Aga Kaiyan, Consul of Iran in Bombay. I could surmise the object

of Dinshah's visit: he had at last arranged to proceed to Iran, with Dr.

Tagore, to fulfill his long cherished desire to kiss the dust of his

beloved fatherland, and, as a dear friend, he would not think of leaving

India without calling on me. But why should the Consul accompany him? I

had not to wait even for a minute for the explanation; Immediately he

entered the room, the Consul said, Mr. Masani, we want you to go with us

to Iran. Do come.

Years ago I had jumped at

the invitation to join, as a delegate, a Mission set up by the Government

of India, to investigate the commercial possibilities of South-Eastern

Iran. Owing to differences of opinion, however, concerning the question of

appointment of the President of the Mission, the Bombay Chamber of

Commerce and the Mill-owners Association, whose delegate I was to be, had

to withdraw from the arrangement. Since then whenever I arranged to go to

Iran, unforeseen difficulties upset my schemes. At last, after

twenty-eight years, when I was immersed in other preoccupations, there was

another call to embark on the oft-frustrated journey.

Curiously enough, on this

occasion, too, I was invited to undertake a commercial mission. “You

know," said the Consul, “the Government of Iran want Parsis to develop her

trade with India. You know that Parsis are also willing to establish

closer relations with Iran. If you come with us and make independent

investigations and then advise the community what business schemes could

be safely and store for us advantageously undertaken, a good beginning can

be made."

This appeal, reinforced by

Dinshah, was irresistible. I tore myself away from the literary work I had

in hand and joined the party. Before our departure the Persia Industrial

and Trading Company was hurriedly constituted with Sir Hormusji Cowasji

Dinshaw as Chairman and myself as Managing Director.

I do not propose to talk

of sordid business in this article, life in Iran interesting though it

would be to trace the genesis of the joint Parsi-Irani concern, the

Khosrowi Mills, established in Meshad, a couple of years later, to the

conversation I had with the Consul and Dinshah on that memorable day. The

object of this article is merely to record a few impressions of New Iran.

|

|

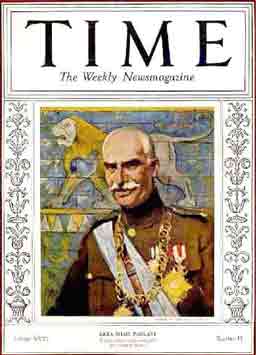

Reza Shah Pahlavi

on cover of Time magazine |

It is a characteristic of eastern countries

that though inert for centuries, once they begin to move, they move faster

than western countries. Iran is no exception. Even before we witnessed

with our own eyes the transformation wrought during the regime of the

present Shah, within seven years after he had assumed the reins of

government in the year 1925, we had heard of several reforms carried out

with lightning speed in the social and political institutions of the land,

and of improvements in the amenities of life, such as the construction of

motor roads in place of mule tracks, the organization of the police and

the road guards to ensure safety, and the electrification of several

cities. I had, however, also heard reports that in respect of of

sanitation Iran was still mediaeval. When, therefore, the time for landing

at Bushire arrived, I was nearer cold feet than ever before throughout my

experience of difficult journeys. It was certain that owing to lack of

sanitation and sanitary conveniences our lives would be made indescribably

miserable until we should reach Tehran. In Bushire we had a foretaste of

the difficulties that were in store for us and during the journey to

Shiraz, and in that city itself, there was the same trouble. Even in

palatial buildings there was not more than one lavatory, and that too of

the primitive type, and a bath-room was a luxury to be met with only at

the houses of those who were doubly blest with wealth as well as the sense

of personal hygiene. For the pilgrims to the fatherland this was by no

means an exhilarating experience. However, as we entered Ispahan, life in

Iran wore an altogether different aspect. Special sanitary arrangements

were made for the guests of His Imperial Majesty. In Tehran and Meshed,

too, there was no cause for complaint.

Throughout the journey

from south to north and from west to east I was greatly impressed by two

remarkable features. The first was the presence of the Amnieh, the road

guards, at short distances. If deterrence of crime and establishment of

law and order could be regarded as the best proof of the efficiency of the

road guard, we had such proof in abundance wherever we traveled. Had I not

traversed, day and night, the far flung areas in all directions, I should

have hesitated to accept the statements I had heard before that the roads

in Iran were absolutely safe. Wherever I went I enquired whether the

inhabitants had heard of any case of murder, assault or theft in their

neighborhood. To my surprise I found that the men from whom I sought the

information had to make an effort to recall any such incident. If after

some minutes they could cite a case of petty theft or violence, it was

easily accounted for as the work of a domestic servant, or a disappointed

lover, or of an inflamed relative. The highwaymen had deserted their

haunts; the professional robbers and law-breakers were frightened out of

their nefarious pursuits.

The second notable feature

was the sight of gangs of laborers repairing or widening the roads. It was

heartening to notice that money was forthcoming to meet one of the

essential requisites of commerce-good communications. The roads were

generally devoid of beauty, but we found that during the new regime

khiābans, boulevards, had been constructed on European model in all

principal cities. The buildings abutting on these boulevards were of

improved and uniform design. Especially at Tehran, Ispahan and Meshad the

Iranis seemed to have been engaged in the work of city improvement similar

to that I had witnessed when the Bombay Improvement Trust took in hand the

Dadar- Matunga Scheme.

It must be admitted,

however, that, on the whole, Persian cities are drab and unpicturesque,

surrounded by equally uninviting walls. Even a city like Shiraz did not

appear to be the peerless garden it was in the eyes of Hafiz. Once,

however, we entered the courtyard of houses we found beautiful gardens and

rooms neatly furnished and decorated with some real gems of Persian art

such as a carpet illumining a corner or a curtain hanging over a door or a

window.

What appeared to have been

sorely neglected was an adequate system of water supply and drainage.

Through many a street little canals of water were seen bubbling along in

the open or coursing underground in a channel having a few openings. Here

we saw Irani men and women squatting and performing their ablutions. If it

was a woman, her couching figure was busy rinsing Swabs of cloth. The

dirty water flew onward to be used by others waiting at a distance with

pots to clean, kiddies to bathe, or sores to wash.

No wonder the toll

annually taken by typhoid and other water-borne diseases was excessive.

I had not gone to Iran

merely to pay my homage to the fatherland. It was my mission to study

conditions and investigate prospects of strengthening the ties between the

Parsis and the rnodern Iranis and of developing commercial relations

between India and Iran. The defects, therefore, could not escape myeyes.

But Dinshah was there merely to preach the gospel of love, to kiss the

sacred soil of Iran and the burly Iranis, too, who greeted him with kisses

and shed tears of joy in embracing him! He had, therefore, no eyes to

notice things which to me appeared to be serious handicaps.

The strongest point in

favor of Iran is its climate. It helps to cover a multitude of sins

of insanitation and slovenliness. Nature is also bountiful as regards the

food supply. The most fateful test by which ruling dynasties and cabinets

stand or fall is the bread available for the people. Wheat bread is the

principal item of the Irani's food, and wheat in Iran is plentiful. So too

other kinds of grain, meat, eggs, poultry, vegetable and fruit, fresh and

dry.

The cost of living was on

the whole cheaper than in India. Even in Tehran it compared favorably with

that in Bombay. The city was lit with electricity. Water was laid on, the

flushing system of water closets was being gradually introduced, and I was

delighted to find that the Sanitary Engineer who had practically a

monopoly for such work was a Zarathushtrian, Mr. Jehangir Badhni.

One afternoon the Court

Minister, Teymour Tash, took us to the most fashionable club in Tehran. It

seemed to me as if one of the clubs from a continental city, including its

fashionable members, had been transplanted in Tehran! There were the

English, the French, the Swiss, the Germans and the Iranis, and, if the

visitors for that afternoon could be included, the Parsis too, men as well

as women of distinguished appearance and manners, dressed in European

style, partaking of refreshments served in European fashion, and

dancing to the tune of European music. When I was intro~ duced to the

charming Russian wife of the minister, she offered to dance with me. I

apologized profusely for my inability to dance; so did Dr. Sorab

Meherhomji who was standing next to me. Never in my life did I feel so

annoyed with me for neglecting dancing.

The official religion of

Iran is Islam. But I found that most of the Iranis were free thinkers.

Borne Parsis in India believed that as there was a tendency among the

modern Iranis to hark back to the days of Cyrus and Darius, Jamshid and

Noshirwan, they might in course of time revert to the religion of the

ancient Iranians too! Far from it. It is my impression is that there is as

much or as little chance for it as there is for the Irani to embrace

Christianity or Judaism. The fact is that the people of Iran want all to

go there and to take their capital there and help in the industrialization

and regeneration of Iran, but on condition that the Iranis and the Iranis

alone should be the masters in their own house.

When Reza Shah ascended the throne, the

country was groaning under the tyranny of the Mullahs and the brigands.

The brigands have been completely routed; nay, as if by a talisman, the

highwayman of yesterday is turned into the yeoman of today. As for the

Mullahs, they were once the true rulers of Iran, being able to support or

smash any government and to stifle any measure of reform likely to

undermine their hold on the ignorant and superstitious masses. Those days

are gone. Under the new rules a Mullah's turban is no longer regarded as

the sole proof of one's qualifications to be a priest. He has to prove his

knowledge, and innate worth. This in itself has thinned the ranks of those

inveterate enemies of progress. The few that remain have been relegated to

their legitimate position in the State.

Speaking of the masses

over whom the Mullahs used to exercise overwhelming influence, I found the

people as a whole still illiterate and inarticulate. No doubt, they have

natural intelligence and are peace-loving and law-abiding. There is no

caste system militating against homogeneity and unity. Under the present

constitution all the subjects are equal before the law.

|

|

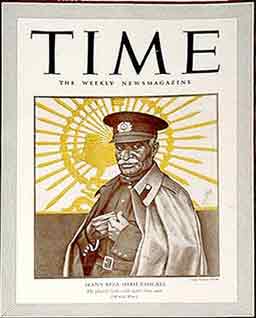

Reza Shah Pahlavi

on cover of Time magazine |

Many a traveler has

lightly passed judgment on the character of the Irani. I should not

presume to generalize without wide and intimate experience spread over all

classes and for a long period. That the Irani is a pleasant fellow,

perfect in manners, delightful as a host, endowed with wit and humor,

rather easy going and inclined to live in the sky, is well known to all. I

shall refer to one or two traits of character which cannot be passed over

in silence. He is certainly no slave of the clock and in no hurry to

start. A meeting may be fixed for five o'clock; business may not begin

till six o'clock. But in respect 0£ this lordly trait of character Dr.

Tagore might well claim to have excelled the Irani, for he seemed to have

made it a rule to make his audiences wait for nearly an hour, no matter if

ministers and courtiers, the honored guests of His Imperial Majesty, the

President of the Irani Anjuman of Bombay and the Managing Director of the

Persia Industrial and Trading Company, included, should be swearing all

the while!

You may be invited to

dinner at eight o'clock. It may not be served till ten o'clock. You

wonder if there would ever be an end to the stream of salutations, shafts

of witticisms and the rounds of tea without milk offered to you. Tortured

by hunger, you may sip the tea or chew the dry fruit or shirini

(pastry) laid in front of you.

Readiness to please you or to concur with you,

although unconvinced, is another peculiar trait in the Irani's character.

Such an anxiety not to differ or displease, has been often misunderstood

and variously interpreted. The fact is that he generally does not want to

deceive you but gives you merely an evasive answer if he thinks that the

truth, if told, would be unpalatable to you or savour of incivility. For

instance, if he tells you that the road along which you are to travel is

good when it is bad, he is merely trying to be pleasant to a visitor from

a foreign land. If you ask him to do a thing or fetch something for you,

he would invariably say chashm (with my eyes), but would not often

move even his little finger. You might wait patiently for him to turn up

and bring what you wanted, but you might as well wait till Doomsday. Once

I was much annoyed at such loss of time repeatedly inflicted on me and

said to the Superintendent who was looking after our comfort on behalf of

the Darbar,

"My dear friend, if I ask you to do something which you cannot carry out,

there would be no harm in telling me it is not possible. But you always

say chashm

and do nothing and upset my

time-table! For a man like me who has many things to attend to within the

very few days I am here, this is a great hardship." Smilingly he replied:

"My dear sir, you do not to understand that I simply cannot say NO to

anything you say or ask. Even if I cannot comply with your wishes, I must

say YES, otherwise I should be guilty of being impolite!” When I related

this incident to Dinshah, he laughed heartily but added a few words,

lawyer-like, in defense of the lying Irani.

One of the most interesting features of New

Iran was the New Woman. Emancipated from the tyranny of the "purdah",

she was free to move about wherever she willed and as she willed, veiled,

unveiled or semi-veiled. Very few, however, came out without the black "chaddur",

which concealed their face, figure and dress. Most of them wore the peak,

which shaded the eye, till they drew up the “chaddur” over the lower part

of the face at the approach to a stranger. Monogamy was understood to be

the rule. There was, however, that singular system of temporary marriages,

called sighé, legalized by ecclesiastical law, on payment of a

small fee, for a fixed period ranging from one day to ninety-nine years.

In Meshed, especially, many a pilgrim - from neighboring lands was

expected to relieve his loneliness by contracting a temporary marriage.

Until recently, child marriages were not

prohibited. Under the new rule,

however, such unions are forbidden. Divorces are still swift and

plentiful. The Pahlavi regime has given to the wife the right to demand

dissolution of the marriage tie for a valid reason, but the husband

continues to enjoy the privilege to divorce a wife at a moment's notice

according to his caprice. Such inequalities seemed to have provoked much

resentment among the new women of Iran. When we were in the country, the

Society of Patriotic Irani Women, a branch of the Shir-o-Khurshid,

the Red Cross Society of Iran, was agitating for the abolition of the

institution of temporary marriages and the law of divorce. The bulk of

Irani womanhood appeared, however, to have been still submerged in

ignorance and superstition. Even in the household of cultured Iranis women

generally lived an isolated life in the anderoon, the interior of

the house. They were seldom seen in the biroon, the separate house

in the same compound where their husbands received visitors.

Now a word about the Shah.

On the 2nd May, 1932, we had the honor of being presented to His Imperial

Majesty. While we were waiting in the audience hall, during the time the

poet was closeted with the Shah, I found myself transported to the realms

of romance and history. One by one the stirring scenes of prowess and

glory of the illustrious sovereigns and heroes immortalized by Firdousi

flashed across my eyes. Many a monarch had since ascended the throne of

Iran and descended into dust. Not a few of them had been endowed with

kingly attributes, but within a few minutes I was to greet one, who,

according to all reports, had excelled his predecessors in innate worth.

Dr. Tagore came out; we

were ushered in. There I saw Reza Shah, the symbol of Iran's unity and

nationhood, standing in the center of the room, dressed like a soldier.

There was something singularly charming in the personality and presence of

this monarch which, for the first time in my life held me spellbound. Cool

and collected, agile and alert, superb in stature and majestic in

demeanor, he gave one an idea of kingship incarnate. Dinshah was the first

to be introduced. Then came my turn. The Minister for Foreign Affairs,

Aghai Fouroughi, muttered the name Rustom Masani. With eyes beaming in

astonishment, as it were, His Majesty exclaimed: "Rustam-e-Sani"

(the second Rustom)! We all laughed heartily, but the comparison made the

pigmy namesake of the national hero mortally ashamed of his stature!

His Majesty’s message to

us was simple and straightforward. He expressed his regret that the

descendants of the ancient Iranians had very little contact with their

fatherland. He wished to see more of them. He did not ask that they should

take their money with them from Hindustan to Iran, Although he was anxious

to see the resources of Iran developed and the Parsis taking a hand in

it." Come in small numbers," he said, "see things with your own eyes; wait

and watch and then decide for yourselves whether some of you should not

sett1e down in the country of your ancestors. We will welcome you with

arms outstretched.”

Article taken from

“Dinshah Irani Memorial Volume,” published in Mumbai, 1948

This article

reflects on the evolving conditions of Iran under the progressive rule of

Reza Shah, the founder of modern Iran. Reza Shah was forced to abdicate by

the British after Iran was invaded by the allied forces in the opening

years of the WWII in order to control the Iranian oil fields to gain

access to roads. The conditions changed and reverted to the old order

with the advent of the Islamic revolution of 1979.

Darabar is the

Farsi word for “The Royal Court”

Responding Chashm

in Farsi means that it will be done

Purdah or Chaddur

was the veil woman were forced to wear to cover themselves in a

traditional Islamic society. The justification for women being forced to

wear the head to leg cover was to protect the men (male dominated society

where women were considered as mere material possessions) from getting

sexually aroused.

This was part of

the great reforms introduced by Reza Shah’s initiatives |