|

|

Pl. 11. Jamshid Soroush

Soroushian, Berlin, 1939. |

|

Rare it is to find caliber

and resolve so happily blended as in the person of the august Jamshid

Soroushian whose memory is exalted and perpetuated through these

commemorative volumes; it is hoped that this biographical note will do

some measure of justice to that revered memory. (For portraits of persons

mentioned in this article, refer to the following collection of historical

photographs.)

|

|

Pl 5. c. 1896. Students at

Kerman's Zartoshty school for boys.

Identified in the picture:

* Soroush Shahriar Soroushian (Jamshid Soroushian's father),

** Faridun Shahriar Soroushian (Jamshid's uncle),

+ Keikhosrow Shahrokh, at the time a young school teacher in Kerman. |

Going back along four

patrilinear generations before the late ra'is, we note Soroush

(Pls. 5, 8), Shahriar (Pl. 6), Khodabaxsh and Jām. Jām, it is believed,

originally hailed from Yazd. The provision of precise datings for this

early period is unfortunately impossible. His son Khodabaxsh lived and

worked in the mid-nineteenth century, out of Kerman’s Gabar Mahalle or

Zoroastrian Quarter to which the Zardushtis had long been restricted. With

the resilience and resourcefulness born of acute hardship, he journeyed as

petty commodity merchant south to Jupar and nearby villages eking out a

living to support himself his jobbing spouse and four sons. In those

uncertain times of high infant mortality exacerbated by great poverty and

dearth of health care, it became the norm to produce large families in the

strenuous hope that some, at least, from the generations to follow would

somehow survive.

Khodabaxsh himself

succumbed to the rigors of a severe winter ─ he would then at the utmost

have been in his early thirties, leaving the oldest boy Shahriar, aged

nine when this calamity overtook the family, to cope as best he could with

preserving his mother and younger siblings from an inevitable destitution.

|

|

Pl. 6. 1897. Kerman: Gathering of

the Zoroastrians of Kerman. Seated in the front row (L

─

R) second person (with white beard) Mulla Gushtasp Dinyar (served as

4th president

of Zoroastrian Anjoman of Kerman), Dastur Rostam Jahangir Hormuzdi

(Head Mobed of Kerman, also served as the 3rd

president of the Kerman Anjoman), Shahriar Khodabaxsh Jām

(served as 5th president

of Kerman Anjoman), and Percy Sykes (later knighted by the British

Crown) who established the British interest section in Kerman. |

The compelling story of

Shahriar's providential encounter at a time of acute physical hardship

with the khazer folk and the subsequent revitalization of his

fortunes, forms part of the Soroushian family's stock of ancestral legends

to this day. As the young merchant's trade prospered, he teamed up with

the business house in Kerman of the respected Arbab (Mullah) Gushtasp

Dinyar (Pl. 6), formerly of Yazd, where his industry advanced him in

prominence. He duly married Mullah Gushtasp's daughter Banu (Pl. 8). After

Gushtasp Dinyar's demise, his wealth was distributed among Zoroastrian

communal relief projects; his residence was bequeathed for the purpose of

commencing schooling for Zoroastrian boys. Girls were denied all public

education; in the privacy of their homes, old customs and venerable

traditions were instilled, ensuring a rich continuity of cultural values

and deep familial ties whose enduringness over the generations triumphed

through an enforced exclusion into the full light of modernity. With

equality of status for women regained, as attested in the early history of

Zoroastrianism, the long repressed distaff side assumed its rightful place

in family and public life.

Banu Gushtasp, a

redoubtable lady, married Shahriar who came to be regarded as Pedar-e

mellat or Father of the Community. Banu herself became affectionately

recognized as memas, Grandma Banu, and thus was established the

Patriarchate of the Soroushians amongst whom the story of the arranged

marriage of their son Soroush to IranBanu, the daughter of Shahriar's

brother Esfandiyar had been planned, it is maintained, before their

respective births (with presumption, of course, of gender difference).

Shahriar's son, Soroush, grew up to accordingly wed his first cousin

Iranbanu, the very slightly younger daughter of Esfandiyar and his wife

Sultan-e Bahram.

|

|

Pl. 8. 1920. Picture taken in

Kerman showing three generations of the Soroushian family. L─R:

(seated) Faridun Shahriar Khodabaxsh Jām

Soroushian, holding his oldest son Shahriar, Banu Faridun Shahriar

Khodabaxsh Soroushian (young child standing at his knee); Kaikhosrow

Faridun Shahriar Khodabaxsh Soroushian held by Mrs. Khorshid

Farmotani (standing ─

3rd row); Memas Banu (Jamshid Soroushian’s paternal grand mother),

Parviz Soroush Shahriar Khodabaxsh Soroushian (young boy at her

knee); Soroush Shahriar Khodabaxsh Jām

Soroushian, holding his third son Esfandiyar

Soroush Shahriar Khodabaxsh Soroushian; Jamshid Soroush Shahriar

Khodabaxsh Soroushian; Katayun Soroush Shahriar Khodabaxsh

Soroushian; Mr. Hormuzdyar Naderi (younger step brother of Memas

Banu) standing. |

Jamshid (Pls. 8, 11, 13,

15, 19), whose life story is encapsulated here was born in Kerman, like

his other siblings from this harmonious pre-ordained union on 8th November

1914 shortly after the outbreak of the Great War. The far-reaching

repercussions of that pan-European conflagration were to be felt

throughout Iran, and most keenly along the "buffer zone" of influence

between Imperial Russia and Great Britain. Now on a war footing, the Great

Game continued relentlessly to unfold, with Imperial Germany making an

aggressive bid for supremacy along the politico-military wedge recklessly

driven in the push for ascendancy by the conflicting Western Powers. Too

young to be affected by these insidious tensions foisted upon his beloved

Kerman, Jamshid spent his infancy nurtured in the bosom of his close-knit

family. He primarily attended the Kerman Zoroastrian boys' school up to

the best grade offered there. His higher education followed at the

day-school establishment conducted by Christian Missions, first in Kerman,

and then as a boarder at the Church Missionary Society School in Isfahan

run along English Public-school lines. Here students from different ethnic

and religious backgrounds were taught; Jamshid was the only Zardushti

pupil, which singled him out for ridicule of his religious beliefs and

attitudes. The school officials were more circumspect with regard to those

from Christian and Muslim backgrounds. Those irksome experiences served

only to strengthen Jamshid's faith and resolve him to inquire further into

his Zoroastrian heritage and his community's affairs and background ─ a

deep involvement ensued which, if anything, burgeoned throughout his life

and defined his future career. He became wholly committed to his people,

his family, and to a sound scholarship for which the Isfahan mission

school had unwittingly equipped him. His spirit and intellect bonded

wonderfully within him, begetting high ideals of life and of character,

and impelling him surely towards his goal of restoring a long awaited

glory upon the noble faith of his ancestors in the very heartland of his

beloved Iran.

|

|

Pl. 13. 1949. Baghin (20 Miles

West of Kerman): Arbab

Sohrab Rostam Kaikhosrow Viraf Kianian (president of the

Zoroastrian Anjoman of Yazd

─

wearing a hat and holding his grand daughter Mahvash Jamshid Soroush

Soroushian) has accompanied Professor Ibrahim Pour-Davoud (standing

to his immediate right) to Kerman. Jamshid Soroush Soroushian

(president of Zoroastrian Anjoman of Kerman) is standing to

Professor Pour-Davoud's immediate right. Other well wishers, part of

the welcoming party have also posed for this photo session. |

An older sister Katayun

(Pl. 8) and a younger Mahindokht together with three brothers, Parviz

(Pl. 8), Esfandiyar (Pl. 8) and Hormuzd completed Jamshid's generation.

Shahriar the

well-remembered patriarch, had assiduously built up a modest agricultural

business through careful management of the several small-holdings around

Kerman. Under Soroush and his brother Faridun (Pls. 5, 8, 12), it further

expanded with land sales by Qajar royalty to land holders, and happened

also to include cultivable land near Tehran. This latter acquisition had

been facilitated through the kindly offices and good influence with the

Qajar families of Arbab Keikhosrow Shahrokh (Pls. 5), the then Zoroastrian

representative in the Majlis at the national capital.

Jamshid stalwartly resumed

his family's business activity whilst absorbing himself in penetrating

studies of his ancestral religion and civilization. He had encountered the

research work of the Parsi solicitor Dinshah J. Irani (the father of

Professor Kaikhosrov) who had twice visited Iran ─ once accompanied by

Rabindranath Tagore. Impressed with his profound interest in Zarathushtra

and the promulgation of his wonderful universalist message, and that of

his like-minded distinguished Iranian colleague Ibrahim Pour-Davoud (Pl.

13), Jamshid soon adopted the latter as mentor and revered teacher. Pour-Davoud

was long remembered by him for his tremendous qualities of heart and mind.

|

|

Pl 15.

March 1964. Kerman: Family

picture taken on the occasion of NouRuz at the family residence.

Front row L─R:

Armity Jamshid Soroushian, Jamshid Soroush Soroushian, Homayun

(Sohrab Kianian) Soroushian, KhorshidBanu Sohrab Kianian, Anahita

Jamshid Soroushian.

Second Row L─R:

Mehrborzin, Mahvash, and Soroosh Soroushian.

(Background: A custom décorative Kermani Carpet commissioned by

Jamshid Soroushian, capturing a historical scene of Achamedian

Emperor Xerxes and his queen Esther.) |

No ordinary bibliomane,

Jamshid found time to pursue his Zoroastrian studies and fulfill an

unselfish ambition for enlightening his co-religionists everywhere.

Remarkably, his religious interests and convictions were directed

outwards, yet held within the bounds of his intense nationalism. All the

works he was to produce in the field of historical and religio-cultural

research were in Farsi, and his comprehensive collection of literature on

these subjects reflected as much on the endeavors of Iranian savants as on

the scholarship of outsiders who had devotedly immersed themselves in

studies of the ancient Iranian civilizations.

Over the years he had

welcomed overseas visitors, students and investigators of this

far-reaching ancient culture, rejoicing in their company and in evaluating

their noteworthy contributions. He maintained a lively correspondence with

many scholars abroad and would visit them whenever possible during his

travels outside Iran. It is good to confirm that several papers reproduced

here are from his friends, colleagues and admirers who can easily and

appreciatively recall his spontaneous welcome and traditional hospitality

in his bustling Kerman home which many regarded as informal education

center. Thus Jamshid Soroushian's multifaceted personality ─ he was a

scholar, but even more a man of the religion and a leader of the community

─ explains the choice of papers included in this volume: not only articles

by scholars, but also contributions by friends and co-believers who wished

to testify their admiration for the man.

Kerman itself held a

sacrosanct place in Jamshid's heart. Has it indeed not been said of this

marvelous symbiosis of city and citizen by Shah Nematollah Valli,

Kermān dēl-e 'ālam-ast,

ā mā ahl-e dēlīm.

Jamshid had a formidable

acquaintance with the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi Tusi which he

tactically used with great effect and with much frequency in resolving

thorny situations demanding persuasion and diplomacy. It always worked! In

addition to his undoubted business acumen, his extensive erudition became

widely respected both among his fellow Zardushtis and those not of the

faith. He was elected to the high profile position of rā'is-e anjoman,

in which prestigious capacity he served as guiding light to his

beloved community. It is pointed out that he was the tenth occupier of

that office. His brother Parviz stood later as the twelfth incumbent.

Since boyhood Jamshid had

been afflicted with mild deafness. In later years this was to intensify to

the point of totality and it is recounted that in his last years he was

able to communicate only through his attentive lip-reading of close family

members. Throughout, his vitality remained undiminished and his unfailing

courtesy amply compensated his many anxious friends, associates and

guests.

|

|

Representing the Zoroastrian community

during a royal visit to Kerman in 1964 by Shah Mohamed Reza Pahlavi |

Jamshid Soroush Soroushian

as scholarly author is best remembered for his Farhang-e bēhdīnān

the comprehensive lexicon of the dārī dialect extensively spoken

among the Zardushtis of Iran until quite recently. But not far behind in

importance ranking are his other published works including Savād āmūzi

va dabīrī dar dīn-e Zartušt (which bespeaks early universalist

education), Ba yād-e pir

muġān

(commemorating

the Magians), Rōšānibāxš (on early Zoroastrian esoteric

traditions), Tārix-e Zartuštiān-e Kermān dar in čand sad sāleh

(outlining past centuries' history of the Kermani Zardushtis),

Pand-nāme-ye Mohammad (putative instructions of Mohammad on the

treatment of vanquished peoples), Šāhnāme-ye haxāmenišiān (a

challenging work presenting subtle aspects of Ancient Iran's Achaemenid

dynasty), and Āb-e garmābe va pākīzākī nazd-e Zartuštiān-e Irān (on

traditional cleansing among the Zardushtis). Jamshid's last completed

work, Čāšt, (including chapters on the maltreatment by the Arabs of

the Zardushtis of Balochistan) has recently been posthumously published;

his unfinished set of chapters of an incomplete draft awaits editing with

a view to publication.

In the year 1946 Jamshid

married Homayun (Pls. 15, 19), the daughter of Arbab Sohrab Kianian (Pl.

13) of Yazd. She bore him five children over the course of a long and

steadfast marriage: the eldest daughter Mahvash Goodarz (Pls. 13, 15), was

followed by sons Soroosh (Pl, 15) and Mehrborzin (Pl. 15), and their twin

sisters Armaity Shahriari (Pl. 15) and Anahita Soroushian (Pl. 15).

His links with Yazd were

additionally reinforced through his studies on Yazdi history and culture,

and between the two ancient Zoroastrian stronghold cities, he thoroughly

imbibed and vigorously propagated the precepts of the Good Religion. His

long-time friend and editor of the Persian Section volume, Emeritus

Professor Bastani Parizi, remarked of him, "Jamshid expects his audience

in the span of fifteen minutes over tea with him to realize the merits of

the Dīn-e bēhī and to become believers in it!" Indeed a fervent

Zardushti!

|

|

|

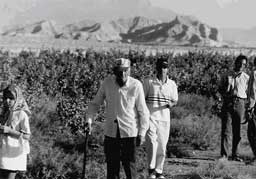

Pl. 19. Summer 1998. Jamshid

Soroushian inspecting a pistachio garden in Saidi (North-Eastern

Suburb of Kerman). His grand son, Vishtasp Mehr Soroushian is

walking behind him. Ruins of a 3rd century

C.E. mountainous fortress named after the Sasanian Shah Ardeshir can

be seen in the background. |

On his last visit away

from Kerman, Jamshid Soroush Soroushian suffered a stroke in Tehran and

expired on 28 February 1999. His remains were brought to his beloved home

city and there inhumed in the family plot, between his dearly revered

parents, in the Zoroastrian burial ground. A staunch traditionalist in

socio-religious matters, it is believed that he regretted the ending of

the system of exposure within dakhmas some two generations ago ─ (the Yazd

Manakji dakhma, however, remained in use until the early 1960's) ─ but was

of a mind which kept pace with changing events and new developments. His

humanitarianism and breadth of vision overrode considerations of ancient

usages when they could no longer continue to be validated. For him it was

the progressive Zoroastrian way, and he departed this life as he had lived

it: in dignity, peace and in the due fullness of time.

While Jamshid's heart was

devoted to his family, both domestic and extended, his soul was anchored

in Zoroastrianism. Inasmuch as he diligently attended to the family

business of agronomy which flourished under his careful stewardship, he

carved out time for his concerns for his community and its material and

spiritual well-being. He encouraged the education of all to the utmost

level of their abilities, and from the humblest of the Soroushian

enterprises' employees to the highest among his many acquaintances, he

ensured that such opportunities were always made available. It could

sincerely be said of Arbāb Jamshid that brightly as the ritual Fire

burns externally, his unquenchable spiritual Fire blazed up gloriously

within him. Truly, it is his Ātaš-e dorun ─ the Fire within ─

which we reverently commemorate herewith! May it ever blaze forth to

illumine the living soul of Zoroastrianism!

Ašaonąm

frauuašim yazamaide.

[1]

Reproduced in most parts from

ĀTAŠ-E DORUN -

The Fire Within: Jamshid Soroush Soroushian Memorial Volume II, 1st Books

Library, Bloomington, Indiana, 2003, pps. xi-xxxvi. |