|

|

A mayor of Kerman, Iran

residing over the business of the city about sixty years ago, once

expressed to visitors from the capital his wish that the rest of the city

would follow the lead of the residents of Gabr-Mahalla[ii]

(Zarathushti quarters).

To the surprise look of

his visitors not expecting such a complement to be paid to a minority

group, the mayor went on to explain that the residents of the Gabr-Mahalla

on a regular basis clean inside their houses as well as broom the alley

and public passages outsides their houses. After brooming the alleys

outside their homes they regularly spray water (that they labor hard to

get) to keep the dust down (most city alleys and roads were not paved

yet), and in the morning they regularly burn good smelling scents over the

fire that helps keep the air nice smelling and fresh. The mayor who

could have been equally talking about the Gabre-Mahallas of Yazd or

villages around Yazd, went on to say. Compare that with the rest of the

city, where the residents treat the public walkways outside their homes as

their local garbage dump and show no regards for the environment.

[iii]

Kermanís Gabr-Mahalla in

its current locality became home to the surviving Zarathushtis of Kerman

some two centuries ago.

[iv] In time it became

very self sufficient with complete set of schools for boys and girls

(Kermanís first high-schools), a kindergarten, Fire temple and other

Zoroastrian religious centers, a sports facility, community halls, Medical

clinic, a hostel all provided through private donation of the residents of

the Gabr-Mahalla whose pride of ownership made it a model neighborhood in

the city.

A unique feature of the

Gabr-Mahalla was the fortress like walls of each home, and the crocked and

narrow alleys snaking through much of the neighborhood - all designed to

provide maximum protection to its inhabitant. The tall walls would have

made it difficult for the ruffians and Moslem Zealots to scale and cause

harm to the vulnerable Zarathushtis who had no protection under the Qajars.

The narrow alleys served to make it difficult for the herds from rushing

the houses. Each house was built with condensed living quarters,

basements and secret places to store preserve-able food items for the

times of duress and during the winter months. There were also secret

passages between homes including joint roofs, through water canals to be

used as a last resort if a house fell to the ruffians and the inhabitants

had to run for their lives. Most houses had their own water well, and a

courtyard with trees, mostly fruit trees, but often a Cypress (evergreen)

tree.

The occasions that proved

most stressful for the inhabitants of Gabr-Mahalla included times of

national upheavals such as regicides, when there could be a total break

down of law and order at local levels, and the minorities would have been

the most vulnerable groups. Also during the Muslim Holy months of the

year, firebrand Islamic cleric speaking to Mosque crowds and inciting

violence against the Zarathushtis could have sent mindless followers

running in the direction of Gabr-Mahalla to inflict harm.

Although the Gabr-Mahalla

was predominantly inhabited by the Zarathushtis, there were few Moslems

inhabitants mostly converts to Islam residing in the homes inherited from

their parents. There were also some wealthy families belonging to minority

Moslem sects who preferred and felt safer setting up residents in the

company of Zarathushtis in the Gabr-Mahalla. The foreign consulates that

at one time operated in Kerman preferred the ambiance of Gabr-Mahalla. The

consulate of Czarist Russia as well the brief period the Ottomans operated

a consulate in Kerman had set up shop within the perimeter of the

Gabr-Mahalla or just on its boundary where the consulate staff would live

too.

The large consular complex

the British operated in Kerman, although not within the bounds of the

Gabr-Mahalla, was closer to the Gabr-Mahalla than the rest of the city and

was bordered by properties owned by Zarathushtis.

The few long terms foreign

residences of Kerman, including Greek merchants, a Bulgarian prince

(fleeing the communistsí take over of Bulgaria) also preferred the

Gabr-Mahalla. One of the survivors of Ottomanís Genocide of Armenians of

Anatolia who had fled Eastwards to Kerman, was also anchored to the

Gabr-Mahalla and had taken up residence just on the boundary of the

Gabr-Mahalla.

One of the oldest movie

houses of the city - set up by Zarathushtis - was also on the boundary of

the Gabr-Mahalla.

The security and

prosperity of the inhabitants of Gabr-Mahalla improved drastically after

1925 when the Qajars were ousted by the Parliament of Iran and the Pahlavi

dynasty was voted to replace them. From that point with the protection of

law being extended to all Iranians including minorities, and with major

improvements in the conditions of the nation, the Zarathushtis of the

Gabr-Mahalla started a gradual move to the upcoming national capital of

Tehran in realization of greater opportunities. The pace of departure

increased further following the 1979 Islamic revolution with many

Zarathushtis heading overseas. A small number of Zarathushtis remain

in the Gabr-Mahallah, and some have moved to more upcoming-affluent

Western neighborhoods of the city.

The improved conditions

the Pahlavi era afforded Iran and the Zarathushtis of Iran, also meant the

old protective housing structures were no longer needed, and new

architectures started to be introduced. The improvement the Iranian cities

saw in that period, also meant paved broad streets were introduced by the

city government into the Gabr-Mahalla to replace some of the narrow

alleys.

Some departing

Zarathushtis sold their parental homes. There was no shortage of willing

buyers interested to move in. Other departing Zarathushtis kept their

properties or rebuilt them and maintain them long distance. Another group

donated theirs to the Kerman Zartoshty Anjuman for use and upkeep, and yet

another good trend emerging is to convert the houses they grew in, into

student hostels to be donated to the Kerman Anjuman for the benefit of

Zartoshty students from other parts of Iran attending one of the many

universities set up in Kerman. One of the universities has its campus at

the stately home of a Zartoshty family on the boundary of the old

Gabr-Mahalla.

The only time during the

reign of the Pahlavi dynasty that the security of Gabr-Mahalla was

threatened by mobs, happened in August 1953 in the aftermath of the

political upheavals in Tehran fostered by prime minister Mossadegh (also

spelled Mosadeq, Mossadeq) that led to Shah Mohamed-Reza Pahlaviís

departure from Iran. Although much of the drama played out in the capital,

leftist mobs in Kerman inspired by Mossadekh attacked the house of a

Zartoshty family in the Gabr-Mahalla that had hosted a family wedding few

days earlier. The mobs stormed in to loot the house, broke the arm of the

lady of the house inflicting injury on her. Through the fast action of

some of the guests who slipped out, and called upon a Zartoshty military

leader for help, the damage done was limited. Although, the army was

staying in their barracks and had not received any orders to deploy, that

young Zartoshty officer, Arastu Khosrow Soroushian, who was very much

respected by his troops and colleagues, ordered the soldiers under his

command out of the barracks and towards the Gabr-Mahalla. Hearing about

the approach of the troops, the mob disbanded. The troop stayed and

provided protection to the Gabr-Mahalla. Law and order was restored once

the Shah returned a few days later.

The term Gabr was given a

new dimension in the Persian vocabulary by those who meant to demean the

adherents of ancient Iranian religion, something that was not of

Zarathushtisí choosing. Gabr-Mahalla on the other hand, a place of their

making, where they could control and despite their meager means, they

turned it into a prime location reflective of their rich heritage. Now the

legacy of the Gabr-Mahalla - that even includes a derogatory term - is

part of that proud heritage.

|

|

A view of the ancient mountainous

fortress named after Sassanian Shah Ardeshir overlooking the

Gabr-Mahalla from the South side. |

|

|

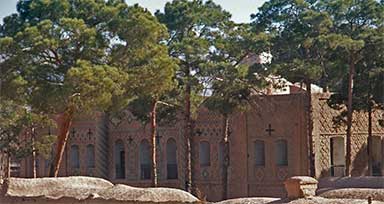

View of the rear of a Stately home of a

Zartoshty family defining the boundary of the Gabr-Mahalla, now

serving as a university campus. |

|

|

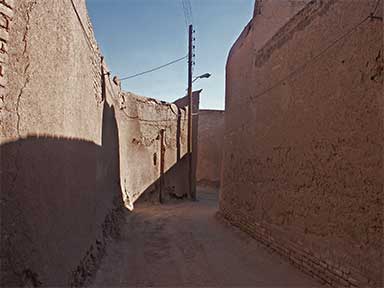

One of few remaining

old alleys of Gabr-Mahalla reminiscent of yesteryears. |

|

|

New Fire Temple of Gabr-Mahalla fueled

by Natural Gas |

|

|

New housing complex

built on the premises in the Gabr-Malleh where once the Russian

Consulate in Kerman stood |

|

|

A Zartoshty community Hall in the

Gabr-Mahalla built with donation from Rustom Soroushian Kermani, a

byproduct of the Gabr-Mahalla, who moved to upstate New York in

early 20th century and became a successful businessman. |

|

|

More and More the

New Face of Gabr-Mahalla |

|

|

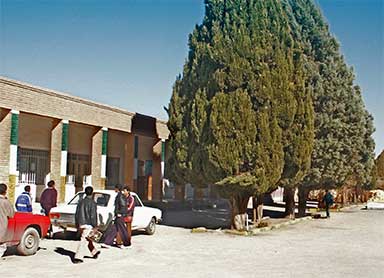

The Campus of

Iranshahr Zoroastrian Boys High School of Kerman, the first

high school in Kerman, that was run a community school by the

Zoroastrian Anjuman, now taken over by the government |

|

|

The Campus of Kaikhosrow Shahrokh

Zoroastrian Girls HighSchool of Kerman, amongst the first

high-school for girls in Kerman, that was run a community school by

the Zoroastrian Anjuman, now taken over by the government and used

an a high school for boys. |

|

|

A Medical clinic in the Gabr-Mahalla

built on donation by Mr. Khodad Mehrabi, a businessman who grew up

in the Gabr-Mahalla and moved to London in the early part of the 20th

century. |

[i]

This visual essay was posted on October 24, 2004 based on photos taken

on site in Kerman in 2003 and 2004.

[ii]

The term Gabr, a derogatory term used by fanatical Moslem in Iran

implies adherents of the Zoroastrian religion. Mahella is a Farsi word

meaning neighborhood.

[iii]

The mayorís quote was reported by Emeritus professor of history

Mohamed Ibrahim Bastani Parizi of Tehran University in his book on

history of Kerman. He does not mention the mayorís name.

[iv]

For more information on Kermanís CaberMahella refer to the book,

City and Village in Kerman, Iran, by Professor Paul Edward

English, University of Wisconsin Press, 1966, pps. 45-49.

|