|

|

|

|

Sheheryar Kaoosji,

1971 |

Mr. Sheheryar Kaoosji is remembered as a

caring man, who lived a life helping everyone selflessly. Scion of a

respected Parsi family of Hyderabad-Deccan, India, he was the twelfth of

fourteen children of Kaoosji Dadabhai Talukhdar and Gulbanoo of the

Viccaji Meherji family.

His father

had served the Nizam of Hyderabad as a talukhdar (head of a district) and

in the tradition of the day adopted his vocation as his name. With Kaoosji

Talukhdar’s passing his children adopted their father’s first name as

their family name…hence, the Kaoosji family of Hyderabad.

Sheheryar’s

brothers and sisters were either civil servants or teachers. Most of them

had a special attraction to academic life and enjoyed intellectual

exchanges, often hosting the local Persian intellectual club, the

Bazm-e-Saadi, in their home.

|

|

Sheheryar and Parvis Kaoosji, 1967 |

Sheheryar’s earliest recollection of his

father was of a man who had lost most of his eye-sight to cataracts. He

had watched his elder brother, Dadabhai, read aloud to their father, from

his vast collection of Farsi and Urdu books. Those early impressions no

doubt left a lasting impact on the young Sheheryar, who lost his father to

the influenza epidemic of 1918 when he was barely 8-years old. So when he

grew up and time came to choose a career, he dedicated his life to

rehabilitate the blind, in a personal tribute to the father he adored,

respected and had such little time to know well.

He was a

student of the prestigious St. George’s Grammar School and kept in close

touch with his alma mater all his life. His sons followed him to the same

school. Later in his career, wherever occasion arose, he paid homage to

the school and his teachers, especially the Principal, Canon F.C. Phillip.

|

|

Sheheryar Kaoosji with

School for the Blind Band |

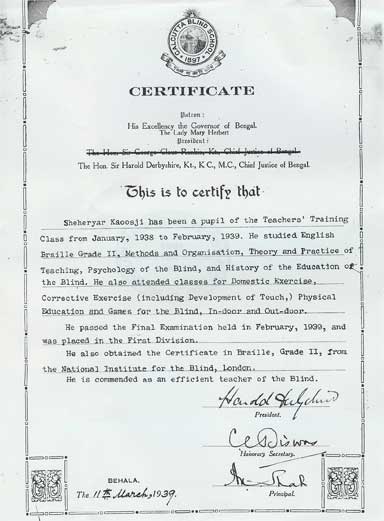

Soon after

graduating from the Nizam College where he led an active student life as a

hockey player, an amateur actor and debater, he went to Calcutta, to the

Behala School for the Blind where he qualified himself for his chosen

profession. Upon returning he started work to establish an institution for

the rehabilitation of the Blind in Hyderabad. As the Headmaster of the

Government School for the Blind he pioneered their education in Hyderabad,

and advocated for the welfare and mainstreaming of his students as

productive members of society. He fought successfully to admit his

students into the Osmania University, and today there are several well

educated visually handicapped men and women who are active in various

walks of life, thanks to his vision, perseverance and energy.

His career

and family life ran a close parallel. Just as he was settling down in his

career he married Parvis Taraporewalla, on January 5, 1941. She held a

Diploma from the Royal Drawing Society, London, and was the art and

needlework teacher at the Mahbubia Girls School. She had attended the

same school as a student, and worked there as a teacher, and retired after

a distinguished 35 year career in 1970. They had three children.

|

|

Kaoosji at Helen

Keller Reception |

Another

passion and lifetime involvement of Sheheryar’s was the Boy Scouts. He

joined the scouting movement as a student of the St. George’s Grammar

School, and remained a scout for life. As a school teacher he was also a

Boy Scout Commissioner, and at every institution he headed, he made sure

to introduce a Boy Scouts troop. He was very proud of the Blind Boy’s

Scout Troop in his school, which had one of the better known marching

bands among scout troops in town.

A civic

minded and responsible citizen, he was very concerned about the communal

discord between Muslims and Hindus following Indian Independence in 1947.

The atrocious impact on human life and suffering brought on by the events

following the partition of India was as severe on Hyderabad as anywhere

else. But it was minimized in the wake of the international dispute over

Kashmir that still looms large over the subcontinent more than half a

century later. The Nizam of Hyderabad (the largest native princely state)

had decided to remain an independent monarch and refused to join the newly

created India or Pakistan. He took his impractical and fairy tale case to

the United Nations, and even engaged the eminent British constitutional

jurist Sir Walter Monckton to advise and represent him. But this fancy

legal battle took a nasty turn on the streets and neighborhoods of

Hyderabad, which were witnessing sporadic communal rioting and violence.

Extremist groups of Muslims supported the Nizam, and Hindus wanted him to

join the newly downsized India. A peace-keeping force was created and

Sheheryar Kaoosji heard his calling, and promptly volunteered to be

Commander of the Civic Guards Corps in his neighborhood of Gunfoundry. He

was 36 years old, a father of two sons, 6 and 4 years old, and a soon to

be born daughter. Along with his corps of guards, both Hindu and Muslim,

he as a Parsi held the balance of peace and commanded their respect and

loyalty. He patrolled the streets with them every night, keeping the

peace. On one night he almost lost his life while breaking up a brawl

between warring gangs. Years later he used to proudly show us the spear

gash between his third and fourth ribs, always grateful that it was on his

right side.

|

|

Sheheryar Kaoosji

receiving the National Award, 1960 |

Soon after

Indian Independence, Sheheryar Kaoosji was awarded a Colombo Plan

Fellowship and spent two years studying practical implementation of modern

social work techniques at the University of Adelaide, in Australia. Social

work was as much his passion as the education of the blind. When he

returned he was disappointed that the new State government did not take

any action to utilize his training and education in the broader social

services field. But he was happy to return to his School for the Blind.

In 1955

under the cultural outreach initiated by the Eisenhower administration,

the renowned Dr. Helen Keller visited India. Sheheryar Kaoosji served as

the Liaison Officer for her visit to Hyderabad. He was always very

thrilled that he was fortunate to meet and host a world leader in the

rehabilitation of the handicapped. Those present at the Civic Reception

recall his passionate and oratorical introduction of Dr. Helen Keller.

|

|

Sheheryar Kaoosji

Award Citation |

In 1956, five years after his return from

Australia his services were loaned by the Andhra Pradesh State Government

on a special assignment as Superintendent of the quasi-government Victoria

Memorial Home, an orphanage plagued with corruption and mismanagement.

The orphans had been neglected, and funds for their education and

rehabilitation had been swindled. The institution at that time housed a

couple of hundred orphans most of them a sad reminder of the Police Action

of September 13, 1948, when Hyderabad was annexed by Free India. The army

under General J.N. Chaudhuri overran the district of Mahbubnagar killing

many civilians and leaving hundreds of orphans. It fell on Sheheryar

Kaoosji’s watch once more, to close another chapter of the horrors that

India’s partition brought. He rehabilitated over a hundred young men and

women. He found suitable working class men to marry the young women, most

of them illiterate with few skills. He used his influence and friendships

with old classmates from school and college, to hire young men as

apprentices and put them on a road to self sufficiency. He introduced

vocational training in the institution. Within a few years he transformed

the Victoria Memorial Home from being a warehouse for orphans into an

effective rehabilitative institution it was established to be. In 1959,

once again, he happily returned to the School for the Blind and led it

till his retirement in the late 1960s.

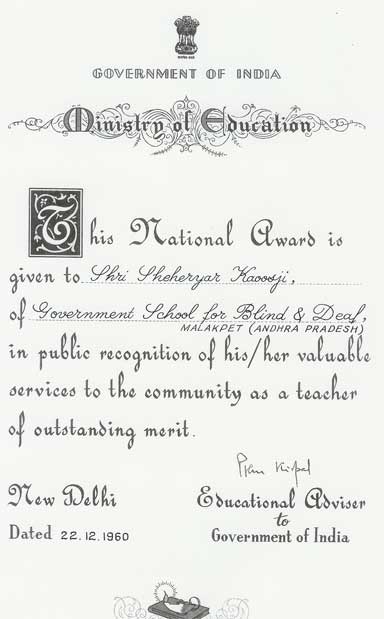

Sheheryar

Kaoosji’s professional work was singled out for honor by the Government of

India. In 1960 he was the first recipient of the National Award for

Teachers, conferred personally by Dr. Rajendra Prasad, the first President

of the Republic of India.

He was a

very intellectual man, and had a profound interest in comparative

religious studies. He loved to compare and study religion as a process of

human development. A devout Zoroastrian, he drew upon his knowledge to

study and comment on the inter-twining history of the religions of the

world. His best work in this area is an article he researched and wrote at

the time the world was celebrating the 2,500th Anniversary of

Cyrus the Great. Titled “Cyrus the Great and his World Embracing

Personality and Humanity in the Light of the Holy Quran and the Holy Bible”,

his paper effortlessly links a scholarly deduction of the references to

“Zul Qarnain” in the Quran and the Jewish scriptures to conclude that it

is no other than Cyrus the Great. He could speak for hours quoting from

Jewish, Christian, Islamic, Buddhist, Hindu and Zoroastrian teachings, and

raising religious discussion and deliberation to a higher plane, always

critical of dogma and ritual in every religion. He maintained that

professional priesthood often did great injustice to the principles of any

faith, by introducing dogma into religious discussions. He was a very

popular speaker at Muslim gatherings during the celebrations of the

Prophet’s Birthday.

He also had

a great sense of humor and was an excellent actor. The life of any party,

he never hesitated to spontaneously entertain young and old alike. We

fondly remember when he surprised us at a large Nowroze gathering of the

extended Kaoosji family and friends. He dressed up in his sister’s purple

gara (embroidered Parsi Sari) and stumbled into the dining

hall, leaning on a cane and mimicking a well known dowager in the funniest

Parsi Engrati (English & Gujarati). He acted out how she used to

carry her age and status around, pushing children aside to grab the first

seat at free gambhars in Secunderabad.

After his

retirement he kept busy in the social welfare arena, managing a shelter

for women called “Aram Ghar” (Rest Home), and for the last four

years of his life he managed the administrative office of the Parsi

Zoroastrian Anjuman of Hyderabad & Secunderabad.

|

|

Sheheryar Kaoosji

Braille Diploma |

When he

became administratively responsible for the Anjuman’s affairs, it brought

him closer to issues related to Dakhma Nashini. For years I had

accompanied him to funerals of relatives and friends, and he kept getting

more and more disturbed about the urban sprawl that brought housing right

to the compound walls of the Bansilalpet Dakhma in Secunderabad.

From being a remote and isolated Dakhma, it was now uncomfortably

surrounded by a neighborhood, which was getting equally uncomfortable

about its presence. The Parsis left the carting of the cortège through the

crowded streets to the poorly paid Nussasalars (professional pall

bearers), while the family members themselves whizzed in and out in their

cars. But my father always walked behind the cortège, and personally

witnessed the verbal abuse by the neighbors, objecting to this hazardous

nuisance in their neighborhood. The Dakhma, with all its

environmental, ethical and philosophical glory had become an anachronism.

Worse was happening, and continues today, at the Towers of Silence in

Bombay. These towers, in turn dwarfed by towering apartment buildings lie

open to the view of the neighbors, who watch the slow decomposition and

devouring of human bodies by chained vultures, insects and the tropical

climate. All in the midst of this cosmopolitan metropolis.

For

Sheheryar Kaoosji, it was difficult to claim cultural elegance, neighborly

love and charity as the cornerstones of faith for a practicing

Zoroastrian, while simultaneously disregarding basic human decency,

sanitation, aesthetics and respect of other human beings. He objected to

adhering to a system that was a culturally abhorrent carryover of an

archaic custom, designed for a different geography of remote mountains and

deserts of Persia, and the culture of another era.

Ever a

problem solver, he sought to open a dialog to convert the Dakhma

property into a graveyard. This was not a new idea. A hundred miles away,

in Nizamabad, there was a properly consecrated Parsi Aramgah (A

resting place … graveyard). And, there were many more all over

India. He had visited Nizamabad and maintained that this is the best

compromise the Parsis could make to live in harmony as good citizens, and

to ensure our practices meet acceptable 20th century standards

of sanitation, aesthetics and lead to acceptance in the communities where

Zoroastrians live as microscopic minorities.

|

|

Sheheryar Kaoosji

Demise News Item Deccan Chronicle 1974 |

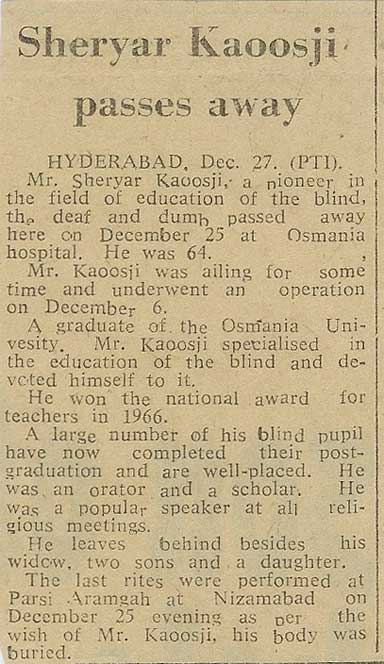

Then the

unexpected happened. Apparently in good health, but having ignored his

personal self for years, he had a relapse and surgery could not save him.

On December 25th 1974, which was Christmas of the Christians,

Eid-ul=Fitr of the Moslems and Ekadasi of the Hindus … three holy days of

three major faiths, he passed away at Osmania General Hospital in

Hyderabad. He was 64 years old. The only way we could honor the one

unfinished business of his life, was to lay him to rest in that Aramgah

in Nizamabad, which we did with great sorrow and pride.

This,

despite the most venomous attacks by so-called elders of the Parsi Anjuman

he served who prohibited the Mobed Sahebs, from entering our house to

conduct funeral prayers. The Mobed Sahebs, as employees of the Anjuman

had no option but to obey their employers. That was probably for the best,

because Sheheryar Kaoosji encouraged everyone to take an active and

personal role in all prayers and ceremonials. He himself had prayed and

conducted the Zoroastrian part of my marriage to Irene, while her uncle

Benjamin Israel blessed us with Hebrew prayers, at our civil wedding just

three years earlier in 1971. So, along with my Mother, siblings, aunts and

uncles, we had the privilege to say our heartfelt farewell to him with

Zoroastrian prayers, as we laid him to rest according to his wishes.

I look back nearly thirty years later at this

episode as a lost opportunity for the Parsi community to make a mature

societal decision. But, for the extended Kaoosji family, a pioneer act

has been fulfilled in honor of Sheheryar Kaoosji. Since 1974 all deceased

members of Hyderabad’s Kaoosji, Taraporewalla, Bastawalla, Dubash and

Mistry families have been either buried or cremated.

In closing

this tribute, I must add that Sheheryar Kaoosji loved to recite poetry,

whether it was in English, Farsi or Urdu, and one of his favorite poems

was the classic “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” by Thomas Gray,

and I quote the final verse of The Epitaph:

No

farther seek his merits to disclose,

Or draw his frailties from their dread abode,

(There they alike in trembling hope repose,)

The bosom of his father and his God. |